These pages are copied from Jessie’s site in Britain, which is not easily accessed in China. The reason for duplicating her site is to work around the Great Firewall, which specifically blocks any site containing the character string ‘wordpress’. I added photos and occasional comments. You do not have permission to copy or print these, only to read them.

If you want to get in touch with her and cannot access her site, write to me first.

DJS 2012

thefilthycomma #54

The Life of Breath project has engagement with schoolchildren as one of its stated aims, encouraging them to look after their lungs the same way they might look after their teeth. The public health approach towards smoking in teenagers in particular has been prevention rather than cure in recent years, because what one ex-smoker friend calls ‘getting the tobacco monkey off your back’ is so difficult.

Smoking is an addiction, often treated as a nicotine or tobacco habit, with patches and other forms of nicotine-replacement. However, any former smoker will tell you that physical routine is a strong element of the addiction, and that even simple things such as wanting something to put in one’s mouth or hold in one’s fingers can trigger the craving far more quickly than the smell of second-hand smoke. As so often happens in the phenomenon of the ‘Proustian rush’,[1] smells and other bodily sensations are powerful triggers of memories, both good and bad. Indeed, the smell of smoke can take on other psychological associations: many former smokers come to dislike it intensely, while others may miss it and find that their house no longer smells like ‘home’. In my own case as a former pipe-smoker, I missed the pleasant, patient ritual of filling, lighting, nursing and finally smoking the pipe; without it, I felt idle and fidgety and returned to much older bad habits, such as biting my fingernails. Even now, several years after the 2007 ban on smoking in public places, smoking lingers. It seems that the ban has achieved its goal of protecting non-smokers from passive smoking, and smoking has become marginalised and inconvenient.[2] Recently at a train station, I watched a fellow passenger (unlit cigarette in mouth) being moved along by the ticket officer, the hot-dog man and a customer of the nearby model railway shop, all of whom explained to him in turn that he was (as it were) invading their airspace. Obviously humiliated and cross, he persevered, eventually standing awkwardly in a patch of weeds and smoking in a way that suggested it gave him no pleasure.

In recent short years, smoking has changed from a rebellious act to something slightly shameful and pathetic. In my own smoking days (the 1990s), smoking still had something dirty and cool about it. However, whatever advantages pipe-smoking may have as a form of teenage rebellion in terms of originality are balanced out by considerable disadvantages in practical terms, particularly concealment. If caught in the act behind the proverbial bike sheds, a cigarette can be thrown away or crushed underfoot. What can one do with a meerschaum? Push it into one’s pocket, thereby smoking oneself from the outside like a kipper? Even if one were able to tap it out first, the resulting pile of smouldering tobacco remains easily detected with both eyes and nose. Moreover, even an empty pipe is not easy to conceal. One cannot simply quote Magritte and hope for the best. As teenage rebellion, smoking a pipe simply doesn’t work: it is too self-consciously weird, and too old. Cigar- and pipe-smokers are typically male and middle-aged, whether real (Churchill, Castro, Freud, Elgar, J.B. Priestley) or fictional (Gandalf, Nayland Smith, Sherlock Holmes).[3] By contrast, as Matthew Doyle suggests in his essay ‘Sometimes a cigarette is just a cigarette’, cigarettes have a youthfulness about them, a quality that he describes as ‘edge and elegance’:

The fascination emerges from … adolescent exposure to French films, junkie writers, and rock stars … Cigarettes, coffee, idle conversation became the fuel of independence.

Notice how, although Matthew Doyle is writing in 2013, his examples are from several decades earlier. As he implies, young smokers may experiment with smoking in the same way that they might experiment with anything that feels grown-up. It can be a sort of performance, for the benefit of those we know (or hope) to be watching us do something naughty or fashionable. Simone Dennis quotes a conversation with a young smoker:

Megan pointed to the dissolving boundary between cigarette object and her own hands when she spoke of her attempts to ‘look sexy and elegant’ as she smoked. Megan said, ‘I always smoke long cigarettes, Super Kings, and lately, I have been considering using a cigarette holder.’ When I asked her why, she looked disapprovingly at her hands. ‘My hands are really pudgy, and my fingers are short and squat’, she complained. ‘When I hold a cigarette, like this’, she said, holding up her smoking fingers, ‘my whole arm looks longer, and I feel more elegant. It’s like wearing false eyelashes, for that illusion of length.’[4]

Megan also describes using smoke to interact with men, touching their cheeks with it encouragingly (a ‘caress’), or blowing it directly into their eyes (a ‘slap’). As Matthew Doyle notes, the link between smoking and sex is strong: one can find it everywhere from Rousseau’s views on both smoking and masturbation to Roddy Doyle’s novel about domestic violence, The Woman Who Walked into Doors. The woman of the title is Paula Spencer, who develops a dependence on alcohol (which she and others see as aberrant, destructive and isolating) running alongside her dependence on cigarettes (which she and others see as normal).[5] Paula describes seeing her husband Charlo for the first time as follows:

I suddenly knew that I had lungs because they were empty and collapsing … His hands in his pockets with the thumbs hooked over the denim and a fag hanging from his mouth. It got me then and it gets me now: cigarettes are sexy – they’re worth the stench and the cancer … He took the fag from his mouth – I could feel the lip coming part of the way before letting go – and blew a gorgeous jet of smoke up into the light. It pushed the old smoke out of its way and charged into the ceiling. Then he fitted the fag back onto his lip and the hand went back to his pocket. He was elegant; the word doesn’t seem to fit but that was what he was.[6]

It is striking how most smokers can list compelling reasons for giving up, and yet the addiction is so strong that the struggle to be free is more like a wrestling match than a clean, knock-out blow. Don’t teenagers want to smoke in the first place because they’ve been told they shouldn’t? It doesn’t seem surprising that smokers (particularly those who started as adolescents) might see the risks as part of the attraction. Paula is attracted to Charlo because he is dangerous (‘He was with a gang but all by himself’, which we might gloss as ‘he was a gang all by himself’), and she becomes addicted to their relationship, as well as to smoking and drinking. Again and again she fails to throw him out. When she finally does remove him from her life, it is with the same sense of time and youth being victoriously reclaimed that one finds in ex-smokers: ‘I’ll never forget that – the excitement and terror. It felt so good. It took years off me.’[7]

Like Paula Spencer, we all struggle to escape what is bad for us. Teenagers choosing to smoke is more complicated than a simple act of rebellion: tobacco companies cynically exploit this association between smoking and youth, freedom and rebellion, to target young people, in the hope that they will develop a lifelong addiction. Matthew Doyle writes that,

The legacy of the cigarette [is] … a harsh reminder of the relationship between the mind and body, spurring us towards self-reflection and a different understanding of disease and mortality.

Perhaps this self-reflection is what is needed for successful interventions. Watch this space.

——————————–

[1] This term refers to an unexpectedly powerful memory, typically prompted by a smell or a flavour, named after the memories triggered in A la recherché du temps perdu by Proust’s now infamous ‘episode of the madeleines’. Proust himself suffered from severe asthma and other allergies and described himself as ‘allergic’ to cigar smoke. See Mark Jackson, Allergy: The history of a modern malady (London: Reaktion, 2006), pp. 67-68, for a summary of the various asthma treatments Proust experimented with.

[2] Recall the wintry, Soviet-era trek to the new smoking area in The IT Crowd.

[3] This can also be seen in popular adaptations of the Sherlock Holmes stories. Older actors playing Holmes (such as Jeremy Brett) can be seen smoking the Holmes’s iconic meerschaum; indeed, both the actors that played Watson opposite Jeremy Brett were also shown smoking pipes of their own. This is also true of Clive Merrison, who played Holmes in a large number of radio adaptations during his forties and fifties, and often refers to his pipe (tragically taking no advantage of Merrison’s striking resemblance to Sidney Paget’s well-known portrait of Holmes) and. There is no suggestion of pipe-smoking when younger actors playing Holmes, such as Benedict Cumberbatch and Richard Roxborough.

[4] Simone Dennis (2006) ‘4 milligrams of phenomenology: an anthro-phenomenological exploration of smoking cigarettes’, Popular Culture Review 17(1), pp. 41-57.

[5] Smoking is taken as a given throughout the novel: everyone smokes, all the time, including around very small children, as in this treasured childhood memory from Paula: ‘[My father] blew his cigarette smoke so it look like it was coming out my ears’. Roddy Doyle, The Woman Who Walked into Doors (London: Minerva, 1996), p. 9.

[6] Roddy Doyle, The Woman, pp. 3-4.

[7] Roddy Doyle, The Woman, p. 213.

thefilthycomma #53

I wonder how long it will be before class is determined not by income, one’s father’s occupation, school or socio-economic group, but by simply placing a load of foodstuffs on a table and seeing which ones a given person can name; which ones they can use correctly in a meal; and which ones they eat regularly themselves.[1] My mother maintained that she once heard a large lady get out of a taxi in Henley-on-Thames and accost a passer-by by braying at him, ‘my good man, is there any butter in this ghastly little town?’ In my mind’s eye, the lady in question is tall, bold about the nostrils, and voiced by Penelope Keith. While we were living in Henley-on-Thames ourselves, my mother picked up the habit of referring to builders and other assorted tradespeople as ‘little men’. I found this most confusing (as indeed any child familiar with the work of B.B. would). The men in question were rarely little, and yet I instinctively reach for both this awful term and my Penelope Keith voice whenever I have to deal with ‘little men’ myself.

Recently, we had some repairs made to the roof of the railway room, by a local builder named Tom. He came to survey the damage before starting work, which meant actually coming into the house. This seemed to discombobulate him, and he insisted on taking his shoes off and carrying them apologetically as we went in and out of various rooms to give him a decent look at the relevant piece of roof. We are not a ‘shoes off’ household, as anyone could tell from a cursory glance at the carpets, but he seemed more comfortable this way. Tom turned up a few weeks later, startling me by being on time and on the day we had agreed, accompanied by what I will refer to as a sous-builder. They set to work, fortified with horrible tea (I bought it specially, of which more later), and were finished by lunchtime. This meant that they came into the kitchen (each clutching their shoes forlornly) at exactly the same moment as Giant Bear came home for lunch. Lunch that day was avocado on toast because OF COURSE IT WAS.

The previous day, while purchasing the aforementioned horrible tea, I was suddenly overcome by a wave of reverse snobbery. Why, I reasoned, should I assume that builders must want builders’ tea (i.e. as strong as possible, with milk and two sugars)? We did already have some black tea in the house, but I somehow felt that neither lapsang nor Earl Grey would get the job done. And yet it seemed so silly to buy more tea, when we already have an entire cupboard dedicated to it: black, red, green, white, pink, orange and various shades of herbal in both bag and loose-leaf varieties, as well as two filters, a tea-ball and three kinds of hot chocolate. For guests so bewildered that they can only stammer ‘Whatever you’re having?’ we have the Mystery Jar, in which any lone or unidentifiable teabags are housed, and subsequently fed to the indecisive (see ‘Indecisive Cake‘). We are also in possession of no fewer than six teapots of varying sizes, and, bearing in mind that the house usually contains two people at most, twenty-six mugs. In the end, I bought a box of builders’ tea[2] anyway, but stashed it out of sight so as to conceal the fact that I had bought it specially. Halfway home, it suddenly occurred to me that perhaps they might prefer coffee, but by then it had started to rain and I had to take my chances. A few hours into the roof-repairing, we reached the moment of truth.[3]

‘Can I make either of you a cup of tea, Tom?’ I asked casually (or so it would seem).

‘Yes, please,’ he rumbled. ‘Milk and two’. I had an apple tisane[4], and we were all faintly embarrassed. A couple of weeks later, we attempted to purchase an avocado in Sainsbury’s and discovered that the man on the till had never seen one before and didn’t know what it was. Giant Bear said helpfully, ‘it’s a kind of pear’. This did not improve the situation.

————————————————————–

[1] I recently came across a restaurant review online, consisting of a single star and the following plaintive sentence: ‘They made my risotto with long-grain rice. Need I say more?’

[2] When we lived together, S used to refer to this as Normal Boring Tea (also called Ordinary Tea, like Ordinary Time); my friend H calls it Normalitea.

[3] This phrase actually comes from bullfighting, and refers to the moment when the matador makes the final stroke, attempting to sever the spinal cord by plunging his sword between the shoulder-blades of the bull. In doing so, his whole body is exposed to the horns, and if he does not hit his mark, he will be horribly gored. Truth indeed.

[4] My beverage of choice when watching a Poirot.

thefilthycomma #52

One of the joys of working for myself is that I spend so much more time with my books. We dedicated much of last Saturday to purchasing second-hand books, and much of Sunday to making space for them by removing other books. The result is a leaner, tidier book collection, and the reclamation of an entire shelf. Some of the books that will be leaving the house are those that we have, somehow, acquired two copies of: The Once and Future King (see The search for perfection), the complete works of Tennyson and Alan Hollinghurst’s Stranger’s Child were all in this category. Others have been read, and found wanting, such as The Ginger Man (a dreary book about dreary people), Fingersmith (enough with the plot twists! Enough, I say!) and The Story of O (<snore>). Still others have been mined for information that was useful at the time, but for which we have no further need, mainly deadly music-related tomes left over from Giant Bear’s degree.

There is a final category of books bought on a whim, and which must be reassessed on a case-by-case basis when one is feeling less frivolous. This group includes some of the more obscure works in our collection, such as Anatole France’s book Penguin Island[1] and G.K. Chesterton’s absurdist anarchist novel The Man Who Was Thursday, which I was forced to read on the Eurostar after the only other book I had packed was stolen. A thief of questionable motive picked through my handbag, spurning my purse[2], passport and ’plane tickets to Shanghai in favour of my beige hardback copy of Stella Benson’s bonkers satirical allegory I Pose, which I was a mere sixty pages or so into. The novel contains only two real characters, the Gardener and the Suffragette (Stella Benson was one or the other at various points in her life) and I have been unable to replace it, making this one of only two books that I have left unfinished through circumstance rather than choice.[3] He or she also stole my bookmark.

Giant Bear is a co-conspirator in my need to collect books that, at first glance, may not have much appeal. For example, this Christmas I received exactly what I had asked for: a copy of No Easy Way by Elspeth Huxley. Elspeth Huxley wrote one of my favourite books (The Flame Trees of Thika) and, along with Karen Blixen and Laurens van der Post, is responsible for my love affair with Africa-based non-fiction. Unwrapping it on Christmas Day, I enthused to the assembled family that this was just what I wanted. ‘It’s a history of the Kenyan Farmers’ Association!’ I said (surely more than enough explanation?). The physical book itself is instantly engaging: the front and back inside covers contain maps, as every good book should, and at the bottom of the contents page is the following intriguing note:

The title No Easy Way was the winning entry in a competition which attracted over six hundred suggestions. The winner was Mrs. Dan Long of Thomson’s Falls.

Also in the ‘purchased for the flimsiest of reasons’ category is Corduroy by Adrian Bell, another beige hardback, and which I bought because I was secretly hoping it might be a history of the trouser. Bell is the father of Martin Bell (foreign correspondent) and Anthea Bell (translator of the Asterix books into English); he was also a crossword setter for the Daily Telegraph, and I see from Wikipedia that when he was asked to compile his first crossword he had less than ten days to do so and had never actually solved a crossword himself. None of this means he can write a book, of course, but the opening lines of Corduroy saved it from the Capacious Tote Bag of Death:

I was upon the fringe of Suffolk, a county rich in agricultural detail, missed by my untutored eye. It was but scenery to me: nor had I an inkling of what more it might become. Farming, to my mind, was as yet the townsman’s glib catalogue of creatures and a symbol of escape. The true friendliness of the scene before me lay beneath ardours of which I knew nothing.

I was flying from the threat of an office life. I was twenty years old and the year was 1920.

I say ‘death’, but of course all the books found wanting (and/or unwanted) will be going to the second-hand bookshop already mentioned, where no doubt somebody will love them; this is not death as a long and quiet night, then, but a brief flicker between incarnations. Some, however, really are deceased. Regular readers will recall that I admitted to weeping sentimental tears over the corpse of my original copy of The Once and Future King (see The search for perfection). I couldn’t bear to put it on the compost heap or in the recycling, so in the end it went into the woodburner. On the subject of book-burning, I quote the following relevant passage from my novel (see also Seven for a secret never to be told and The lucky seven meme). This is taken from chapter 23, which is called ‘The Rectory Umbrella’ for reasons that need not detain us here. I quote it because in real life, I reserve a fiery death for books that are too precious to compost, whereas in the book, it is only the most objectionable volumes that perish this way:

Father amused himself greatly by building a bonfire at the bottom of the garden (now the vegetable patch) and burning the more objectionable books like a Nazi. Titles burnt at the stake included the following:

i. City of God. Father has never forgiven St Augustine for the Angles/angels debacle.

ii. The complete works of J.R.R. Tolkien. Anything with elves, wizards or other imaginary creatures, countries or languages had better watch out when Father is in a book-burning mood. Not even The Hobbit was spared.

iii. Several hundred miscellaneous science fiction paperbacks. Father sorted the wheat from the chaff by declaring that anything with a lightly-clad alien female, a sky with too many moons and/or any kind of interplanetary craft on the cover was doomed. Despite passing this initial test, Fahrenheit 451 was on the endangered list for some time. However, ultimately it was spared due to the weight of irony pressing on Father’s soul. I imagine this in the form of God with His holy thumb pressed against Father’s eyeballs, like the creepy doctor in The House of Sleep. However, this assumes that Father keeps his soul in his eyeballs (more likely bobbing gently in a jar in the shed, or pressed between the pages of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd)

- iv.The Thornbirds. This was condemned to death by unanimous vote. Mother was reluctant at first, because of Richard Chamberlain. He’s obviously as gay as the day is long, but it didn’t seem quite the right moment to say so (esp. as she would probably have said ‘oh, really, dear? How can you tell?’, or perhaps ‘yes, dear. But, you know, at this time of year the days are getting shorter again, aren’t they?’ Wretched woman). As an elegy, Father read aloud the bit where the father and son die in a bush-fire, in a small, sarcastic coming-together of fathers and flames. If any of us had needed a final nudge, the utterly stupid moment when the son is crushed by a giant pig would have done it.

Looking through my records, it has been several months since I last added anything of substance to my own attempt at a quirky book that someone might take home with them on a whim. However, the more time that elapses between me and my own escape from the threat of an office life, the more likely that is to change.

———————–

[1] For the benefit of any readers assuming (as I did, in my ignorance of Anatole France and all his works) that this title is metaphorical in some way, I should explain that it really is about penguins, until page 39 when the archangel Raphael turns them into people. This is not an unqualified success and the penguins are disconcerted by their new shape (‘They were inclined to look sideways’).

[2] My purse contained multiple currencies (I was on my way from Britain to China by way of Belgium and France), and yet mere money still failed to hold his or her attention.

[3] The other is Absalom! Absalom!, which was the only casualty in a freak handbag-based yoghurt explosion and had to be thrown away.

thefilthycomma #51

This afternoon, having been unexpectedly relieved of an index I was about to start, I finished reading Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls by David Sedaris.[1] This was a Christmas present from me to myself, along with a festive jumper purchased in the post-Christmas sales, when, like a calendar in January, suddenly nobody wanted it. David Sedaris and I are strikingly different in many ways, in that I am not a middle-aged gay man and have so far failed to publish eight books and embark on an international career of signing those books and/or reading them aloud to people. However, on reading Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls, I discovered that we have four striking things in common.

One: we share a mild obsession with owls (see ‘Owl Chess’ and ‘Strigiphobia’). I keep my non-fiction books in my office, and they are (naturally) arranged alphabetically. Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls is on the bottom shelf, with three books by Oliver Sacks on one side and Suetonius[2] on the other. Ideally, Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls would be next to a book by or about an explorer, most likely (for alphabetical reasons) Scott of the Antarctic, had he survived to write such a volume (Let’s Explore the Antarctic with Not Quite Enough Information, perhaps). The owl used as an exploratory device appears in silhouette on the spine, perched on a floating hypodermic as he contemplates the strange, metaphorical wilderness: a treacherous landscape, all highs and lows. There is also a parliament of owls[3] in my favourite essay of the book, which is called ‘Understanding Understanding Owls’.[4] It opens with a consideration of the phenomenon of the owl-themed gifts that Sedaris and his partner Hugh have amassed over the years:

This is what happens when you tell people you like something. For my sister Amy, that thing was rabbits. When she was in her late thirties, she got one as a pet, and before it had chewed through its first phone cord, she’d been given rabbit slippers, cushions, bowls, refrigerator magnets, you name it. ‘Really,’ she kept insisting, ‘the live one is enough.’ But nothing could stem the tide of crap.[5]

I mention this as a counterpoint to the well-chosen nature of the three Christmas gifts already listed, but I do have some sympathy with the purchasers of the various owls and rabbits, because buying presents is hard. I’m delighted when, in the run-up to Christmas, someone I feel we ought to buy something for (but who already seems to own everything they could possibly need) lets slip in everyday conversation that they like, say, the Very Hungry Caterpillar. We were given an owl for Christmas ourselves: a small white one, designed to perch in the branches of our Christmas tree. In a lovely Biblical metaphor, there was no room in the tree and instead we had to put him on the escritoire, where our tiny knitted magi had completed their arduous journey across the music room.[6] They toiled along the top of the piano, clung to the light-fitting for a few dangerous hours, and finally arrived in safety to stand in a semi-circle with the tiny knitted Mary, tiny knitted Joseph and tiny knitted saviour.[7] Behind them, the owl, a head taller than all the knitted figures, loomed menacingly, while we tried to pretend he was one of the uglier angels.

Two: David Sedaris and I have both had a colonoscopy. He is bullied into his by his father, whereas mine was a medical necessity (see Busting a gut), but a colonoscopy is a colonoscopy. His is described in an essay called ‘A Happy Place’, and mine was so completely uneventful that I haven’t bothered to write about it at all.[8] Three: neither of us owns a mobile ’phone, as described at the beginning of his essay ‘A Friend in the Ghetto’. Four: he has a love of subtlety and nuance in words. Here is an example, from an essay about keeping a diary[9] called ‘Day In, Day Out’:

Some diary sessions are longer than others, but the length has more to do with my mood than with what’s been going on. I met Gene Hackman once and wrote three hundred words about it. Six weeks later I watched a centipede attack and kill a worm and filled two pages. And I really like Gene Hackman.[10]

What I like here is his choice of ‘watched’, rather than ‘saw’. ‘I saw a centipede attack and kill a worm’ implies to me that he happened to glance across and see the centipede killing the worm, and that (the two-page write-up notwithstanding) the event itself was comparatively brief. ‘I watched a centipede attack and kill a worm’ implies something both less and more passive: less passive in that this sounds like something that went on for some time, and which he chose to pay close attention to, possibly crouching uncomfortably over the battle so as to describe it with accuracy; and more passive, in that he didn’t intervene to save the life of the worm. Giant Bear and I watched A Hallowe’en Party last night, an Agatha Christie mystery in which a girl is drowned in an apple-bobbing basin after she boasts that she once witnessed a murder. Again, the ‘seer’ and the ‘watcher’ are quite different. Compare ‘I saw a murder; I saw him die’ with ‘I watched a murder; I watched him die’. The seer’s glance happens to fall onto or into something (the carriage of a passing train, for example, as in another Agatha Christie story, 4.50 from Paddington), whereas the watcher has stopped what they were doing, and is emotionally involved in what he or she observes. Finally, it seems clear that even though ‘observed’, ‘looked’, ‘noticed’, ‘witnessed’, ‘saw’ and ‘watched’ are very close in meaning, they are still different enough that ‘I observed a murder’, ‘I looked at a murder’ or ‘I noticed a murder’ simply won’t do.

Religious readers may note that the title ‘The loud symbols’ is a play on the words of psalm 150 (‘the loud cymbals’). I have appropriated verse five, which in the King James translation reads as follows: ‘Praise Him upon the loud cymbals: praise Him upon the high sounding cymbals’. Translation is a wonderful place to look for word-related nuance. In the NIV, for example, this verse becomes ‘Praise Him with the clash of cymbals: praise Him with resounding cymbals’; other translations also introduce the word ‘clash’ or ‘clashing’ at various points and use ‘sounding’ or ‘resounding’ rather than ‘high sounding’. This may seem like a small difference, but it is no such thing. The onomatopoeic ‘clash’ is not a word you can sneak into a sentence without anybody noticing; moreover, it suggests a rather pleasing omnivorousness in the tastes of the Almighty. It doesn’t say ‘Praise Him with restrained Church of England cymbals’.[11] The unmusical, splashy word ‘clash’ implies to me that God is more interested in hearing us praise Him, with joy, sincerity and abandon, than He is in how well we do it. As Thomas Merton said,

If there were no other proof of the infinite patience of God with men, a very good one could be found in His toleration of the pictures that are painted of Him and of the noise that proceeds from musical instruments under the pretext of being in His ‘honor.’

I’ve written elsewhere about nuance (see A bit like the rubella jab), and how a lack of it can mean that we misunderstand events or people, or appropriate a single incident and use it symbolically to make sweeping statements about huge groups. Jane Elliott[12] argues that the insidiousness of sweeping statements about entire groups is at the root of all prejudices, and that these prejudices are learned and perpetuated generation on generation, as shown in her now seminal eye-colour experiment (also called ‘Eye of the Storm’), and that a middle-aged white man who experiences prejudice for fifteen minutes gets just as angry about it as someone who has experienced it since they were born. As I have written elsewhere (see The fish that is black and Punch drunk), it is a natural human tendency to attempt to simplify the world by dividing things into groups, and then making a statement about all the things in that group. It seems to me that such an approach, and its need to over-use and under-interpret symbols is the enemy of nuance. The recent attacks in Paris, for example, are both specific and symbolic. Charlie Hebdo was chosen as the target because of specific cartoons, but also because the magazine and its staff can be used to symbolise ideas: free speech, freedom of the press, freedom to satirise whomever and whatever we like. In other words, it is an act that encourages us to choose sides: people who think like this, as opposed to people who think like that. As soon as you accept that people can be symbols, hurting those people can start to seem abstract, remote and meaningless, as if two anatomically-correct puppets used in a trial for a sex scandal were jostled around in their overnight container mid-trial, and found the next morning in a compromising position, wholly contrary to the testimony of the people they represented. I am not trying to argue that symbols don’t matter; rather, I suggest that they are a means of simplifying (and therefore dehumanising) a particular group, by lumping them together in a way that seems convenient, rather than correct.

Defending a deity (any deity) against satire is a piece of thinking that has become scrambled somewhere. Just as God does not need those who believe in Him to tell Him that He is great (see The uncharitable goat), God does not need those who believe in Him to stick up for Him like a bullied child in a playground. If one follows the thinking of religious extremists whose idea of constructive criticism is to kill a load of people, it seems that they wish others to be frightened into doing like they do, without much caring whether they think like they do i.e. an ‘outside only’ change. That is how the terrorist do; they don’t make a nuanced, cogent argument for their own point of view (i.e. an argument that might persuade people into changing their insides as well, to thinking like they do and doing like they do). I don’t know why this is, but part of my argument here is that, while people are all different from each other (nuance), they also have things in common that help us connect with one another. Terrorists seem very different from all the people I know and their actions are baffling; nevertheless, I think it is important to try to find explanations for them. The best theories I have come up with are as follows. One, terrorists may enjoy the idea that people fear them; it may make people who have hitherto felt like minor characters suddenly feel that they deserve to be centre stage. Two, there may be an element of ‘I am in blood stepp’d in so far’[13]; in other words, once part of such a group, turning back seems as difficult as going on, particularly if the group provides structure, brotherhood, purpose and camaraderie: they may enjoy muttering the terrorist equivalent of ‘By my pretty floral bonnet, I will end you’[14] before embarking on a new and brave mission, like shooting unarmed people or kidnapping schoolgirls. Three, they may think that fear is a more effective tool than persuasion. Four, they aren’t able to make a cogent argument for their own point of view, because their point of view is not built on argument, but their own fear: fear of other large, undifferentiated groups that they understand only dimly, as a series of stereotypes. Terrorists, in other words, are frightened people, and one of the things they are frightened of is nuance. We do, therefore, have at least one thing in common with them.

——————————————————-

[1] Best Book Title Ever.

[2] Best Name for a Steamed Pudding Shop Ever.

[3] I also received A Compendium of Collective Nouns for Christmas. Most of the collective nouns I thought I could be sure of have at least two alternatives, and ‘a parliament of owls’ is no exception: one can also have a wisdom or a sagacity. The book notes thoughtfully, ‘A collective term for owls does not appear in the old books, which as we’ve seen were mostly concerned with game animals. And, of course, owls are solitary creatures’. They then speculate that the term is taken from Chaucer’s poem ‘A Parliament of Foules’, and remind readers of the parliament of owls in The Silver Chair. Best Christmas Present for a Word Nerd Ever. Mark Faulkner, Eduardo Lima Filho, Harriet Logan, Miraphora Mina and Jay Sacher (2013), A Compendium of Collective Nouns (San Francisco: Chronicle Books), p. 142 (see also page 140 for the corresponding illustration).

[4] Understanding Owls is a book, and so strictly I think the title of the essay should read ‘Understanding Understanding Owls’. The typesetter hasn’t rendered it so, but, just as the index I was hoping to do has been outsourced to someone in India who can apparently produce an index for a complex multi-author academic work in a week for less than £250, it may be that the person who did the typesetting didn’t even think the repetition of ‘understanding’ was odd. I freely admit that compiling such an index would have taken me at least twice as long and cost at least twice as much; however, my finished index would actually have helped the inquisitive reader to Find Stuff, and offer some thoughts on how the different topics might relate to one another i.e. it would actually be an index, rather than a glorified concordance and a waste of everyone’s time.

[5] David Sedaris (2013), ‘Understanding Understanding Owls’, from Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls (London: Abacus), p. 176.

[6] Both the escritoire and the music room sound very grand, but I promise you they aren’t. The escritoire came with the house, and we eat in the kitchen, thereby rendering what would otherwise be a dining room useless. We call it the music room because we keep the pianos (one real, one Clavinova), all the sheet music and Giant Bear’s collection of trumpets in there.

[7] The baby Jesus is knitted onto Mary’s arm, so he was (of necessity) a bit previous.

[8] I have also never written about my sigmoidoscopy, a similar arse-based medical intervention. That is because, unlike the colonoscopy, for which one is knocked out, the sigmoidoscopy is done without anaesthetic (i.e. they gave me gas and air, which just made me throw up the nothing that my stomach contained). It’s bad enough that I had to go along with a complete stranger inserting a monstrous chilly tube into my Special Area, never mind talking about it as well. I also wasn’t allowed to wear a bra, presumably so that the needle could judder into the red zone over ‘100% Humiliating’ for as long as possible.

[9] Regular readers will recall that I also kept a diary in younger days (see Broken Dishes, The dog expects me to make a full recovery and He had his thingy in my ear at the time), but since I no longer do so I haven’t listed this as something we have in common. The man writes in his diary every single day and carries a notebook with him at all times, for God’s sake.

[10] Sedaris, ‘Day In, Day Out’, Owls, p. 227.

[11] <ting>

[12] See her here in the early 1990s on Oprah. It’s not an obvious place to find her, but she’s magnificent.

[13] Macbeth, Act 3, scene iv, line 135.

[14] I say this to Buy it Now items on Ebay. Also, Best Line from a TV Show Ever (with ‘Curse your sudden but inevitable betrayal!’ a close second).

thefilthycomma #50

It’s pretty irritating watching treasured childhood memories being chewed up and spat out. We have the new Jurassic Park movie next year, hoping to make us forget that there have already been two grim sequels; recent films of Paddington Bear, Tintin and the Narnia books; there is even talk of a sequel to Labyrinth, for God’s sake. As if re-booting Thundercats in 2011 wasn’t bad enough, somebody re-made Willo the Wisp and thought it would still work without Kenneth Williams doing all the voices. Absolutely nothing is sacred and I am weary of hearing about such projects and not knowing whether to be pleased that there is a little more sauce in the pot, or frightened that the sauce will be poisonous crap. I put this trend down to three things. One, the people who decide what gets made into a film have no ideas of their own, and no idea how to address their own lack of creativity. Two, they are roughly my age and watched the same programmes as I did when they were small. Three, they are bastards. Soon, all pretence at concealment will be abandoned and men dressed as the Clangers will simply break down my front door, go straight to the shelf of children’s books and defecate right onto the pages.

As if this wasn’t bad enough, much like a parade of mournful and bloody Shakespearean ghosts, celebrities from my childhood continue to be unmasked as sex offenders. I used to tell people about the time my mother got Rolf Harris to open our new school nursery (true story. My brother I got signed photographs of that week’s Cartoon Time illustrations); now I feel dirty if I catch myself humming ‘Sun Arise’. Who next? Floella Benjamin? Gordon Kay? Professor Yaffle?

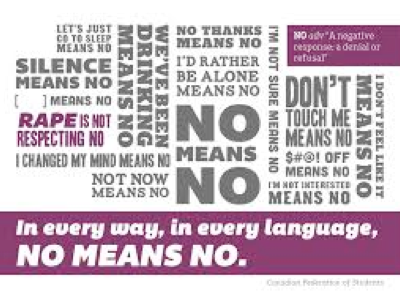

Consider the historical allegations of child abuse that have been in the news recently, going back to incidents that took place thirty or forty years ago. Jinny suggests in The Waves that we should decorate our Christmas trees ‘with facts, and again with facts’. We haven’t decorated our tree or indeed any of the house yet (in true Advent fashion, we are watching and waiting), but for those of you with trees already up, here is an undecorative and completely non-fact-like fact: according to an interview with a battered woman on Woman’s Hour earlier this year, some instances of domestic violence are not categorised as domestic violence, sexual assault, GBH or ABH, but common assault. This is a category that would also include something like a drunken altercation with a stranger outside a nightclub. Actual or grievous bodily harm charges can be made at any time, but an allegation of common assault has to be made within six months of the assault in question. That means that if a woman reporting her partner for domestic abuse is told that her allegations fall into this category, she has to report a specific incident (not years or decades of abuse, but a particular occasion), within six months of that incident. If one thinks for a moment about how long it may take such a woman to be in a position to make such an allegation without placing herself and her children in further danger, this does not seem reasonable.

Imagine a woman who suffers a single incidence of child abuse in her teenage years (at the hands of a family friend, in his car after a lift home from netball practice, let’s say). Now imagine that next door to our teenage netball player is a family, consisting of a middle-aged wife, two small children and an abusive husband. The predatory family friend can be prosecuted at any time. The message that family friend should take away from the many recent high profile cases is that he is never safe: his (now adult) victim can go to the police at any time, and while the traditional barrier of women not being believed is a significant hurdle, he can see for himself that successful prosecutions can and do follow. By contrast, the abusive husband might well get away with a smorgasbord of horrible behaviour for just as many decades, without any negative consequences for him whatsoever, thinking to himself (with some justification, it seems) that his chances of being imprisoned or even arrested are small.

This is for many reasons, two of which I want to think about here. One, the crimes of the abusive husband are not very interesting to the police and the general public. Operation Yewtree is a nationwide witch-hunt against child abusers, but I find it hard to believe that any future government is likely to give the same prominence and resources to a similar campaign to root out the perpetrators of domestic violence. Two, it is much more difficult for abused wives and girlfriends to report this kind of crime. It has been a source of tremendous irritation to me to hear people speak about the women who have alleged mistreatment and rape at the hands of Bill Cosby being criticised for not coming forward sooner. First of all, several of them did so and were ignored; and second, what we should be asking is why women don’t feel able to go public with this information sooner, and then doing something to fix that. Third, maybe women don’t come forward sooner because they expect to be criticised and ignored. Maybe there are other women who would very much like to come forward and report their abusers, who don’t do so when they witness the victim-blaming of women who do. If it’s OK for cases of child abuse to be investigated (successfully! Even in cases when the perpetrator has died!) decades after the fact, why can’t we extend the same courtesy to all victims of sexual crimes? Why do we laugh at Mr. Punch slapping his ugly old wife around, but not when he smacks the baby? Why do we offer ‘he was drunk’ as an excuse for a handsy colleague, but ‘she was drunk’ as an accusation? Why is it OK to abuse a woman, but not a girl?

What I want to explore here is why is it that we are so much more shocked by (and interested in) the sexual abuse of children and teenagers than the sexual abuse of grown-ups. There have been many examples in recent months of people talking about domestic violence and rape in ways that make me terribly angry, and I can’t be bothered to list them all here. Victims of rape, sexual abuse and domestic violence do not need to be told how to behave, or what they could have done to avoid the abuse, or why whatever it was that happened to them a. didn’t happen b. wasn’t that bad or c. is probably mostly their fault. Nevertheless, the phenomenon of victim-blaming does interest me (see A bit like the rubella jab). I wonder if part of the problem is simply that we can all imagine (or remember) what it’s like to be angry with a spouse, and so find it easier to relate to the idea of being violent towards someone who may have been annoying in a low-level sort of way for many years: changing the channel without asking, ignoring our haircuts and consistently leaving the seat up. We find it much harder to imagine molesting a thirteen-year-old in a twilit car after a netball match. However, I think that is to misunderstand the fundamental nature of domestic violence. The women (and men) who are victims of domestic violence do not get a frustrated, end-of-tether smack and then an immediate, shame-faced apology, as my husband would get if I ever raised my hand to him (assuming that his habit of leaving piles of receipts and small change randomly around the house as a sort of low-grade money-based spoor got too much for me). In such a situation, my husband and I would have reached a point where we needed to have a conversation about his annoying habit and my short fuse, which (while possibly heated) would be in the wider context of a loving relationship. The victims of domestic violence are not in any such context. They get their bones (and spirits) broken, over and over again, by someone they used to love and trust; maybe someone they have children with, and maybe who also abuses his children, or beats their mother in front of them; maybe someone they are financially dependent upon; probably someone they cannot avoid, placate or escape; certainly someone they don’t feel able to reason with. Maybe they even still love the person that is hurting them, in a hopeless sort of way.

It seems to me that there are four possible explanations as to why the media prioritises child abuse over domestic abuse. Firstly, child abuse is more visually appealing, because children are more visually appealing. A news editor can print a photograph of our netball player: a frail, coltish girl with a pained expression, looking wistfully into the camera. This can appear above a vaguely titillating story and a much smaller picture of the same woman at the time of the interview. This will sell far more newspapers than, say, pictures of a fifty-year old woman with a broken nose with three decades of physical and emotional abuse to talk about. Secondly, child abuse is clear cut: child vs. molester. The child cannot possibly have encouraged the abuse and is legally unable to consent, so we can be 100% outraged with the molester. Our response can be visceral and sincere, but above all, it can be simple. We don’t feel this way about a thirty-year marriage, because marriage is complex and involves two grown-up people. I think an abusive marriage is pretty clear-cut, actually, but because we have no frame of reference other than our own, non-abusive relationships, it’s tempting to assume that the conflict within other relationships must be like conflict within our own relationship: complex, nuanced, with blame on both sides.

Thirdly, leading on from the supposedly murkier subject of blame within an abusive marriage, I wonder if the third and most disturbing explanation for the way in which society turns away from victims of domestic abuse is that it is too easy to identify with. We’ve all been furious with a partner at one time or another, and maybe even wanted to strike them. I wonder if maybe some people then sublimate that desire into a pattern of behaviour that makes their partner feel that everything wrong in the relationship is their fault (and therefore it’s OK to be abusive towards that person in a non-specific, unprovoked fashion, because they’re bound to deserve it one way or another). It’s not such a stretch from there to striking that person next time we lose our temper. Instinctively, we turn away from our darker impulses when we see them in ourselves, and when we see them in others. In other words, there is never going to be a situation when it’s OK for a grown-up man to molest a teenager, but we don’t find it such a large logical leap to imagine a scenario when it might be acceptable for a grown-up to strike another grown-up. Add to this the culture of victim-blaming I mentioned earlier, and we may find it easy to believe that a thirteen-year-old was unable to resist her attacker (just as she is unable to consent), but may find it harder to believe of an older, larger and more experienced woman.[1] Surely, we say from a position of no information whatsoever, she must have had options?[2] Thus it becomes easier to say ‘poor little thing’ about the netball player, and ‘why didn’t she just leave?’ about the battered wife.

Fourthly, we have the commodification of youth, and of formative sexual experiences. Recall our coltish netball player: one reason that her story is shocking that we feel she ‘deserves’ a ‘normal’ introduction to sexual relationships. However, as I hope every student I have ever taught would immediately point out, that statement doesn’t mean anything until you define the central terms. What do we mean by ‘deserve’? What do we mean by ‘normal’? What do we mean by ‘sexual relationships’? Moreover, why is this girl entitled to a happy, safe, supportive relationship when her neighbour is not? I am not trying to set up a simplistic dichotomy of victims of child abuse have it easy vs. battered wives don’t, because I don’t think comparative victimhood helps anybody (although this kind of relativism is something you will see in the media all the time): my point is that as a society we are far less upset by (and a lot less sympathetic towards) adult victims of abuse than we are towards children or teenagers. I don’t want to say ‘young women are real women, because they fit the ideal that women are supposed to conform to more closely’ vs. ‘older, less attractive women are not really people at all’, but, beyond my tentative suggestions above, I can’t come up with anything better. Would we feel different about Punch and Judy if Judy were younger and/or prettier? I think we would.

It is, thankfully, possible to move on from child abuse and live a normal life. It’s certainly possible to deal with (have therapy for, think constructively about, understand and move on from) a single incident, or even years of repeated abuse. Not everyone is able to do this, but many people can and do. Women (and men) do this all the time. I wonder how easy it is to move on (emotionally, but also financially, practically, and physically) from an abusive marriage. Remember again that such women may have children that don’t know what a non-abusive relationship looks like; that the violent husband is likely to never face arrest, trial or prison for his crimes; and that the ties that bind our battered wife to her abuser are numerous and strong. She may also have her own internal conflicts to deal with. Perhaps she struggles with the concept of divorce for religious reasons; perhaps her children are too young to understand their father’s behaviour and will hold her responsible for removing him from their lives (more victim-blaming); perhaps nobody else knows about the abuse and she will be subject to many well-meaning but ill-informed interventions. Perhaps she also feels a sense of guilt and shame at the situation she finds herself in. I have written elsewhere about my own extremely amicable divorce (see Delete as appropriate). We were both very clear that there was no question of either of us being ‘to blame’ for the end of the relationship. Nevertheless, we both still had to listen to other people’s opinions on the subject; we had also, throughout the long dark patches of our marriage, felt compelled to conceal how bad things were from almost everybody. I stress again that neither of us had anything to be ashamed of, and yet we both felt the need to behave as if the failure of our marriage represented some profound personal disgrace.

In all the recent scandals, there has been a great deal of muddying the waters with speculation and focus on the perpetrators. For example, we can’t talk in an informed way about Bill Cosby and the (at the time of writing) seventeen women who have made accusations against him, because he hasn’t been tried in a court of law, and so we are left wading about in a load of hearsay and weak inferences.[3] I don’t find it difficult to believe or ‘side with’ these women, because I can’t name a single woman who became rich and successful by accusing a male celebrity of rape. I can name several male celebrities who have done just fine with all sorts of accusations of inappropriate sexual behaviour hanging around their necks (Roman Polanski, Francois Mitterand, Woody Allen, Bill Clinton, Francois Hollande, Michael Jackson, John Prescott, Paddy Ashdown, David Mellor, Neil Hamilton). In some cases it even did them good: I don’t think there’s any doubt that many people felt John Major’s extra-marital affair with Edwina Currie did her very little good, but made him more interesting, for example. I can even name one or two men who have served time and yet still somehow manage to go on with their lives, such as convicted rapist Mike Tyson and convicted rapist Ched Evans.

I mention Ched Evans here because his case confuses the issue, by (again) placing the focus on the rapist rather than the victim. Just as in The Accused the emphasis is placed on the consequences of a prison sentence for the lives and careers of the rapists (the poor little rapists!), I find it hard to stomach the sentiment that ‘Ched Evans has been punished and should be allowed to go back to work.’ He continues to deny committing the crime at all and remains completely unrepentant. That matters because a. even small children are told to say sorry when they do something wrong; b. it suggests that prison has had little meaningful effect, which means c. he’s likely to do it again.

We divide those who commit sexual crimes against children (paedophiles) from those who commit sexual crimes against grown-ups (common or garden rapists). The first group are subjects of horror. We can see from the pattern of crimes committed by (say) Jimmy Savile[4], that such people tend to obsessively repeat their crimes, are always dangerous to those around them, have few if any scruples about who they will prey upon, and that (partly because of the horror with which other people regard such crimes) they often choose to murder their victims as a means of protecting themselves, rather than choosing to stop. The second group are treated in a completely different way, even though they are not demonstrably different (safer, less awful somehow). In the US, statistics show that, on average, someone who has been convicted of rape once will go on to commit another five or six rapes. What I mean here is that, on average, a man convicted of his first rape is likely to be convicted of another five or six rapes after that, but of course once we consider the shocking rates of reporting and prosecution, the likely total of rapes he actually commits is probably best calculated in dozens.[5] It is, therefore, vital that when such a person is released back into the community, he expresses contrition, and demonstrates that he has considered and changed his behaviour.

Here is what I am driving at: dividing sexual predators into two groups based on the demographics of their victims and saying that one group is more dangerous or depraved than the other is itself extremely dangerous. Choose a sexual predator at random and examine his behaviour. The pattern is usually as follows: he starts small (cat-calling, flashing); he makes insinuations and threats that become less and less empty; he moves on to threatening and groping women he can access easily, such as girlfriends, sisters, daughters, neighbours and colleagues; his behaviour and his crimes escalate in direct proportion to what he thinks he can get away with, and he continues to assault whomever he can for as long as he can. He stops only when he is compelled to stop.

Finally, the woman Ched Evans raped was nineteen years old at the time of the crime. Nobody would be saying ‘he’s served his time’ if his victim had been nine.

————————————————————————-

[1] This is relevant to the situation I discussed recently (see The fish that is black), where it seemed reasonable to some people that a woman who is scalped in the process of being killed and partially eaten by a killer whale is to blame because she wore her hair long, rather than blaming (say) the people who employed her and others to get into the water with an animal twice the size of any other orca in captivity and known to have killed two people. The first thing that was actually said about this death was that the whale seized her by the hair (swiftly debunked via video footage), including in an interview with someone who had never met the dead woman, who stated that she would have been the first to say ‘she got it wrong’.

[2] I’m not making this up: it was suggested to a woman claiming that Bill Cosby forced her to perform oral sex on him that she should have bitten him in the penis. This is how you know we are through the looking-glass: refraining from savaging somebody’s genitals can be described as equivalent to ‘yes, darling, I’d love to. Remind me how you like it.’

[3] ‘Janice Dickinson doesn’t seem credible because she’s kind of a bitch; Beverly Johnson does, because she seems nicer’ is about the level we’re at, when we should be asking why the word of one man is being trusted over that of nearly twenty women. Here’s an idea: let’s prosecute him for his crimes, and then we’d know beyond reasonable doubt whether he did them or not. Once that’s done, let’s have a conversation about it.

[4] In truth Jimmy Savile doesn’t belong in this first group of sexual predators who prefer young victims, because his victims included women of all ages, including pensioners with terminal illnesses. I mention this here because I think it shows (again) the pointlessness of such categories.

[5] DOZENS <goes for a lie down>.

thefilthycomma #49

I wrote recently about visiting Nanjing Holocaust Museum in 2009 (see ‘Notes from Nanjing’). Today I found the following snippet in one of my many ‘Thoughts and Notes’ documents, jotted down in a dentist’s waiting room and later typed up:

In January 2012 a hundred raiders on horseback charged out of Chad into Cameroon’s Boune Ndjidah National Park, slaughtering hundreds of elephants—entire families—in one of the worst concentrated killings since a global ivory trade ban was adopted in 1989. Carrying AK-47s and rocket-propelled grenades, they dispatched the elephants with a military precision reminiscent of a 2006 butchering outside Chad’s Zakouma National Park. And then some stopped to pray to Allah. Seen from the ground, each of the bloated elephant carcasses is a monument to human greed. Elephant poaching levels are currently at their worst in a decade, and seizures of illegal ivory are at their highest level in years. From the air too the scattered bodies present a senseless crime scene—you can see which animals fled, which mothers tried to protect their young, how one terrified herd of 50 went down together, the latest of the tens of thousands of elephants killed across Africa each year. Seen from higher still, from the vantage of history, this killing field is not new at all. It is timeless, and it is now.[1]

Notice how the final position of the elephants’ corpses makes a statement about what was important to each animal. What I want to consider here is the inference that animals have an understanding of family.

I don’t mean to insult elephants by suggesting that their understanding of family is the same as my human understanding, for two reasons. Firstly, it seems to me that, just as these elephants seem to have divided into two groups (those that fled, and those that didn’t), people might divide along similar lines. Not every person (or elephant) behaves heroically in such a situation, and may not be surrounded by family members at the time. Furthermore, not everyone places family members (people one has not chosen to be associated with) above all others. It seems to me that, for every elderly skeleton in Nanjing shielding another that he or she believed to be his or her kin, there is probably another skeleton belonging to someone who died trying to protect someone of no blood relation at all (maybe someone they didn’t even know). Returning to the dividing line mentioned earlier, for each of these skeletons, then, I think there is likely to be a further skeleton on the edge of the mass grave crawling over the others in an attempt to save him or herself, who may have been in a crowd of strangers, or who saw his/her relative/friend being shot or maimed, but did not feel moved to risk his/her own life further by intervening. In other words, I think the human concept of family and how we juxtapose that against the concepts of friends and strangers, is more fluid and layered than it is in the animal world. Consider, for example, how many people dislike or have limited contact with their closest relations, or feel a sense of dread or foreboding when their closest relations visit. This feeling of dread can coexist with being deeply attached to the relatives concerned, because it isn’t an expression of not loving those people, but of a whole host of other intertwined issues. I find it unlikely that elephants have such fine-grained, complex feelings towards their parents, children and siblings, given that a. they are elephants; and b. elephants typically live in large, matriarchal groups constructed along family lines. It seems more probable that such interactions and feelings are simpler and more straightforward for elephants.

Secondly, it seems to me that anthropomorphizing animals demeans both animals and humans. Clearly many species besides humans have a profound concept of which individuals besides themselves are worth protecting at their own risk, but these concepts and the behaviours that flow from them vary enormously. A mother lapwing will fake a broken wing to draw a hawk away from her babies, but in my own garden I have found the pathetic, wrinkly evidence of blackbird parents ceasing to feed a baby that has fallen out of their own nest, even though it is only a few feet away and has survived the fall unharmed. Animal societies, physiologies and means of expression are so different from our own that I think it is unhelpful and confusing to talk about animals as if they are people, and as if they experience the same emotions that we do.

I watched Blackfish for the first time last week (or, rather, I watched it, went to bed, woke up the next day and immediately watched it again). There is much discussion of the family bonds within groups of orcas: each pod has something analogous to its own language, and adult orcas live with their mothers for their entire lives (their lifespans are comparable to human lifespans, so this is not trivial). The concept of family is, therefore, deeply important to these animals; if anything, the film suggests that it is far more important than it is to humans, who can learn to speak another language if they so desire; can leave and join other family groups (indeed, are often expected to do so); and can often dictate the intensity and duration of family relationships.

It seems to me that attributing human emotions to a domesticated animal such as a pet dog makes some limited sense. Dogs have lived in close proximity to humans for thousands of years, and they have been bred to be docile, aesthetically pleasing and able to remember their name and a set of commands. Dogs, in other words, have a relationship with (and an understanding of) people that orcas simply do not. Orcas are wild animals that live in the open ocean and could easily go their whole lives without seeing a single human being. Moreover, while dogs have spent thousands of years evolving and/or being bred to be obedient and useful companions, orcas have spent thousands of years evolving into things that are good at killing and eating stuff. Although the sections of Blackfish that show various killer whales lunging at or attempting to drown people who were interacting with them peacefully a moment ago are shocking, in some ways the most troubling footage (to me) was that which showed some of the same people interacting with the orcas with great affection and talking about the bond that they feel they have with the animals. I found the question of whether that bond was real profoundly disturbing.[2]

The trainers speak to the orcas as if they are enormous dogs, because they don’t know what else to do. The film makes a good case for the whales being psychologically traumatised, bored, grief-stricken, confused and repeatedly under- and over-stimulated, but we aren’t orcas and (to misappropriate Hegel) can have only a very limited understanding of what it is like to be a wild orca, or what makes an orca an orca (or what makes a killer whale into a whale that kills).[3] Naturally, we turn to things that we do understand: other people, and other animals. The sequences showing mother orcas grieving when their offspring are permanently removed from them are heart-breaking, but I feel that how moving it is depends on the frame of reference being used. Rather than comparing the mother orcas to human mothers, the people making the decisions to separate them from their babies continue to view the orcas as enormous dogs. Domestic dogs don’t much like having their puppies taken away from them, but they seem to bounce back from it fairly quickly, and the expectation seems to be that the mother orca should do the same. However, using a human mother as the gold standard of emotional connection wouldn’t be any better (e.g. removing the young orca when it reached sexual maturity, say, and then expecting the mother orca to think this gave her more time for herself). Indeed, since the orca mother and baby are being separated by humans, the idea of judging the intensity of their grief in human terms at the same time as humans are inducing that grief feels pretty queasy. Orcas live alongside their mothers their entire lives. We don’t.

Something else I have been turning over in my mind since watching the film is whether the three people killed by the largest killer whale in the film (a male called Tilikum) were also in some way the victims of our tendency to misunderstand animals by projecting human emotions onto them. Several of the former trainers interviewed in Blackfish speak of how mortified they are at the nonsense they used to say about the whales performing ‘because they want to’. Seeing the killer whales doing various complex tricks is impressive only if you consider it remarkable that the killer whale is doing as it was asked rather than killing and eating stuff. Plainly these creatures are easily strong enough, agile enough and clever enough to leap out of the water and touch a ball with their nose or whatever, and the fact that they do so should not surprise us: they are able, rewarded with fish, and have absolutely nothing else to do. They are also strong enough, agile enough and clever enough to kill and eat the trainers if they so choose, and the fact that they do this should not surprise us either.

The film makes it clear that there have been many, many near misses: in other words, the truly remarkable thing is that there haven’t been more fatalities. While most of the people featured in the film who worked with the killer whales are shocked and upset that Tilikum has behaved badly (i.e. killed and partially eaten people), there is very little surprise expressed at the people who behave badly: those who capture and kill orcas in the wild; whoever it was that thought buying an orca who is only for sale in the first place because he killed someone was a good idea; those who didn’t bother to tell any of the people working with Tilikum that he had killed a person, during a live show, in front of an audience; those who wrote the nonsense that the staff at Seaworld uttered in good faith; and those who attempted to blame the three victims for their deaths. It is interesting to see Tilikum picked out as ‘a bad whale’ (in contrast with all the other ‘good’ whales) on the one hand, and on the other the faceless mass of venal, callous, stupid, reckless or greedy people. It is as if we believe that whales are fundamentally good and people are fundamentally not.[4]

That brings me on to another very human habit, which is the desire to categorise, just as I did at the start of this post by dividing the elephants into two groups. It seems to me that the managers of Seaworld who continued to allow the whale trainers to work with Tilikum and other whales that were known to be dangerous took the view that these were fundamentally ‘good’ whales who had behaved badly on some isolated occasions. As Blackfish goes on, it seems that those same managers change their minds, and take the view (after Tilikum has killed and partially eaten his third person) that he is a ‘bad’ whale. However, it doesn’t make sense to make a statement about the fundamental nature of a species or one particular individual whale, based on the behaviour of the few animals that can be observed splashing crowds of tourists from a blue concrete tank. The question ‘is Tllikum a bad whale?’ doesn’t make sense, because we have no way of defining the central terms.[5] We cannot explain what we mean by ‘a bad whale’. If we mean ‘a bad whale is a whale that has killed people’ (including two people that worked with that whale and probably felt deeply attached to him), then yes, Tilikum is a bad whale, but the list of other ‘bad’ whales that had given killing and eating a person a jolly good go was extensive and harrowing. Moreover, all of these ‘bad’ whales are likely to have been ‘good’ whales in their natural context, where their skills at killing and eating stuff would be useful and necessary. In some sense, we might even say that these ‘bad’ whales are more fundamentally ‘whale-like’ than the ‘good’ whales that don’t make as much effort to kill and eat stuff. Furthermore, if we mean ‘a bad whale is a whale that could or would kill a person if he got the chance’ then we are left adrift in a sea of things that can’t be determined. We can’t determine why an orca kills a person or whether he thinks or feels anything in particular before or after the event. We can’t determine whether he does this because he has the opportunity or whether it is part of his whale-like nature, although it is worth saying (as is said in the film) that there has never been any record of a person being killed by an orca in the wild. Tilikum has killed three people, but I don’t know if we can even use that to make statements about the fundamental make-up of Tilikum (‘Tilikum is a bad whale’) any more than we can use it to make statements about the fundamental make-up of orcas as a whole (‘all orcas are bad whales’). Blackfish makes a compelling case that captivity traumatises whales such that they may be more likely to unexpectedly turn on their trainers and attempt to kill and eat them, and therefore we might feel more comfortable with the statements ‘all orcas in captivity are psychologically traumatised, and therefore will eventually become bad whales’, but again we can’t be sure whether this is part of their fundamental nature brought out by captivity, or whether this is purely caused by circumstance. Fundamental attribution error suggests that the circumstances a person finds himself in contribute more to his actions that the fundamentals of his character, but I think it would be a mistake to apply that with any certain to Tilikum, because he’s not a person. It seems that the best we can do is to say ‘orcas are very good at killing and eating stuff. Therefore being in a confined watery space with a traumatised orca is not safe’, which is surely something we could have worked out without anyone having to die.

Tilikum now lives in a tank on his own, much like many people who have killed multiple times. As I’ve said, words that humans use to describe human concepts aren’t very meaningful when applied to whales and whale concepts, but if a whale can be said to be lonely, then given all that I’ve said about the duration and depth of the family bonds orcas have with each other, he probably feels something that we might describe as loneliness. I suggest, however, that the difficulty of thinking about this particular whale is that using our own emotions as a frame of reference is inadequate, and using no frame of reference at all gives us no purchase. While the read-across between the massacred elephants in Cameroon and the rape of Nanjing is tempting and obvious, in both instances I struggle to state with any confidence that I understand how any of the people or animals involved felt, or how I might behave in the same situation. I wrote about my visit to Nanjing that ‘No attempt has been made to understand any of these awful deaths and I don’t feel equal to the task’. Here, I feel that a thoughtful and nuanced attempt to make sense of the deaths of the three people killed by Tilikum has been made. Nevertheless, I still don’t feel able to understand.

——————————-

[1] Brian Christy, National Geographic, October 2012.

[2] As Aristotle says (with reference specifically to how whales and dolphins breath), ‘Among water animals, the cetaceans may give rise to some perplexity’.

[3] ‘Can your allegiances be changed? Can you be trusted? What makes you a chaffinch?’ Helen Macdonald, H is for Hawk (Falkirk: Jonathan Cape, 2014), pp. 64-65.

[4] I know orcas are technically dolphins rather than whales, but the term ‘killer whale’ is so loaded with meaning here that I’m using the word ‘whale’ rather more loosely than I would otherwise.

[5] I will leave aside the unanswerable question of whether an animal used to swimming hundreds of miles a day in a family group, and evolved to use its size, strength and intelligence to kill and eat stuff can continue to be considered a whale if it lives in a tank a few yards across, away from all its relatives, unable to hunt, and receiving food by hand from a bucket in exchange for swimming about in an amusing way.

Notes from Nanjing

The following notes (relating to my time in Nanjing in 2009) were found in an old notebook, unearthed this week while I tidied my office.

Day 1, in the airport (Frankfurt)

The smoothest landing coming into Frankfurt that I have ever experienced (I almost slept through it). Going through security I had to remove the 99p bottle of water I had bought in Bristol and drink it before I was allowed into another dingy booth. The German security people thought this frightfully funny and laughed like very efficient drains. I couldn’t see the joke, but perhaps it had been an unusually boring day (or perhaps the national stereotype is inaccurate, and the Germans are a nation of childlike, humorous people). Security in Britain resulted in my incredibly dangerous sun-cream and deadly deodorant being confiscated. The man was unmoved by my argument that sun-cream is too thick to be considered a liquid as such; he was also unable to explain how placing the deodorant in a plastic bag rendered it harmless. As soon as they let me through, of course, I was free to stock up on other, more sinister fluids at the duty-free Superdrug.

I rode the travelator, but this turned out to be a lot less fun on my own. Now I am reading A Dance to the Music of Time (which, so far, I don’t much like), sitting on a comfy chair by a weird bakery (pastry the size of your head, madam? How about if we encrust it with unidentifiable purple crap?), from whence ‘Tainted Love’ is blasting out. The bakery also serves beer (because this is Germany and there is a probably a law about it) and a Chinese man, who might even be on my onward flight, is wearing a purple cardigan that almost matches the pastries, visibly more relaxed than when he arrived and with three empty steins in front of him. Opposite me, a woman is reading the most German newspaper in the world: an edition of Das Bild, with the headline ‘HITLER IN BERLIN SCHATZ STOLLEN’ and a picture of a naked women crouching over a Bratwurst in the middle of a field. The TV cycles ads for HDTV on mobile ‘phones, urging us to watch CNN on a screen the size of a golf-ball. Don’t they see how they undermine their own sales pitch by telling us this via a screen nine feet long?

Day Six, Nanjing

Signs I Have Seen: ‘Dagoba’ as a misspelling of ‘pagoda’ (‘we can’t possibly repel a Buddha of that magnitude’) and a sign in the hotel clamping down on guerrilla sewing cells (‘No Smocking’).

Day Ten, Nanjing Holocaust Museum

P [Chinese colleague] suggested that we [myself, colleague James, and John, the husband of our American colleague] might visit a museum together on our day off, which we thought sounded like a fun and educational way to spend the day. The taxi pulled up outside an enormous building with a statue of a weeping woman on the pavement beside it. This should have told us that ‘fun’ and ‘educational’ were the wrong words entirely.

The signs in the holocaust museum, commemorating the Rape of Nanjing in 1937, are confused about how many people were killed – it might be 30,000 (all the students in Bristol), or it might be ten times as many (the entire population of Bristol). Either number is plausible in a city of so many millions of souls.

First there are piles of dusty bones in fish-tanks (almost all adult femurs. They do not look real). Then we move into a darkened room with illuminated glass boxes around the walls. The signs, as I say, are curiously uninformative. There is no mention of the thousands of (actual) rapes perpetrated by Japanese during the (metaphorical) rape of the city itself and I wonder if this is because they simply don’t ‘count’ in the face of so many murders. P seems largely unmoved, and I think James and John are more surprised at being taken on a fun day out at a holocaust museum than anything else. I am comparing this room with Pit 1 in Xi’an. The terracotta warriors marching away in perfect silence are creepy after a while; one keeps expecting them to step forward (all of them, all at once). They don’t, of course.