The issues of devolution are not going to go away. Scotland has an increasing appetite for independence and, as it explores what its nation actually wants, it discovers at the same time what it can do. As that transfer of power continues, so the regions of England inevitably shout “Me, too!”. I look here at where we’re at, what we think we want and what is possible.

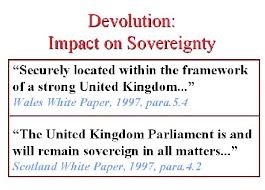

I take as assumed that UK sovereignty is not an issue

, though I suspect there are significant portions of Scotland and Wales that feel otherwise. I see a need on the world stage for the country to continue to be a 60 million size. Conversely, I see a need or demand for a smaller unit of perhaps 2-8 million, sitting between the constituency and the nation; we use the term region for this.

Where we’re at:

1997/8 saw voting in Scotland, Ireland and Wales, resulting in the National Assemblies. A table here from the BBC shows the major devolved powers to be Education, Health, Housing, Agriculture, Education and Environment. Reserved powers1 must include foreign affairs, defence, international relations and economic policy. We can add to that energy (e.g. nuclear energy installations) and immigration. For Scotland2 we add non-devolved constitution (though remember Scotland has its own justice system), some transport issues and defence; for Ireland3 nationality but justice and policing was devolved in 2010. Wales is differently restricted, making laws (‘measures’) in defined fields such as education and health.

Attitudes in England have been studied by the IPPR4 who counted 22% of the population in 2003 and 40% in 2010 who call the situation in England unfair. I found other varying figures, not shown here.

The extended devolution to Scotland gives it tax-raising powers...... what, exactly, is not clear to me....

I’d like to insert the results of regional referenda, but I’m having trouble finding them. Help?

So what do we want in England? We run a serious risk that the politicians will turn this into a political football and screw the whole affair up by playing on the fears of the public without attempting to be sensible. See comment. What we may get is a constitutional convention, in which case the whole idea may be treated as shelved when we should be active participants. What we need to hear is what is possible and what is doable, so that we can choose from the sensible list whatever is desirable.

Down in the South West there is a strong Cornish identity but weaker sense of such in neighbouring counties. There were three models for the South West proposed in 2002: (i) a single elected regional assembly (ii) two assemblies, one solely for Cornwall (iii) a single assembly with special arrangements for Cornwall. A unitary authority in Cornwall could exist but would make little difference to local governance. The possible budget for a Cornish Office or equivalent would be small. See Mark Sandford’s paper. I remember the Cornish vote, which was a wholesale rejection of a unitary authority. This, to me, had far more to do with the way the issue was presented (you can’t afford it) than with what we might want, or how we would like to be governed. Of course, those in power read the result one way quite different from the way revealed in published letters to the local newspapers.

The 2002 white paper, ‘Your region, Your choice’ discusses the possible routes for devolution and forms (I think) the framework of what is considered possible. If you don’t know about your Regional Development Agency, read Chapter 2. The idea is to move accountability and decision-making closer to those affected; it builds upon an expectation that people wish to take part in politics (small p).

Underlining differences in the regions, I found this:

1.3 As an example, since 1989 the growth in GDP per head has been significantly lower in the North East and North West than in the South East and East of England. Some of the causes and results of different regional rates of growth are apparent. For instance, in the West Midlands, North East, Yorkshire and the Humber, and the East Midlands, the proportion of people of working age with no qualifications is more than one-and-a-half times that in the South East and South West: around 19 per cent in the first group, compared with around 12 per cent in the second. The proportion with degrees in London (25 per cent) is almost two-and-a-half times that of the North East (10.4 per cent). Other measures also show regional disparities: for example, the death rate from coronary heart disease among men aged under 65 is over one-and-a-half times higher in the North West (over 63 out of 100,000) than in the South East (around 39 out of 100,000).

The diagrams and tables do not transfer well, so I refer you to the paper itself.

On this topic, Alan Trench is an authority - and a readable one, at that. He is quite good at stating what is and asking what is wanted while not telling us what we should want. There is a certain inevitability that delivered devolution means that Scotland and Wales [will] have self-government. We have yet to agree where the limits are drawn but possibly up to tax-making provision without surrendering defence, international relations, whole-nation economics, politics and government. Trench [2008] points to four purposes of devolution, which I quote in an edited form - hopefully I have not destroyed the sense:

First, devolution would create a distinct democratic voice for Scotland and Wales. This would, in principle, redress the ‘democratic deficit’ that had arisen under Conservative rule. It would also bring government closer to voters, in a way that could be connected to other aspects of new Labour’s ‘modernising’ agenda.

The second purpose was about the practice of government, by providing for local control of public policy. (i) For economic matters, there was a limited conferral of powers for economic development, but within a single UK-wide economy. Macro-economic policy (interest rates, taxation, currency decisions) and micro-economic ones (business regulation, the labour market and employment law) were reserved to Westminster, and so devolved powers amounted to an exhortation to try to do better than the UK as whole, not a licence to create a distinctive Scottish or Welsh economy. (ii) For welfare state functions, such as health, education or housing, this control was supposed to operate within a UK-wide welfare state, which would imply the different administration of common (UK- or Britain- wide) policies. So Scotland or Wales could run their National Health Service in a different way, with political accountability to their own legislatures and ministers, not Westminster or UK ministers – but there would still be a recognisable cross-UK NHS.

The third and fourth purposes were more nakedly political. The third was to undermine political nationalism by satisfying the demand for self-government.

The fourth goal was to create a bulwark against the return of a Conservative government. Devolved government would serve as a barrier to the imposition by Westminster of Conservative policies that did not attract support in Scotland or Wales, because the devolved institutions would have responsibility for many aspects of policy that mattered most on the day to day level.

Paraphrasing more brutally, using brown for proper quotes: The design of devolution was timid. Westminster remained formally and legally sovereign, and has continued to have a huge influence over politics across the whole UK. This is partly a result of England’s size and importance, with 85 per cent of the UK’s population and slightly more of its Gross Domestic Product. [...] Finance remains in the UK Government’s hands, and although block grants give the devolved a great deal of spending autonomy, they also remained tied in to UK funding decisions and the UK public finance system. Westminster remains active as a legislature, for devolved as well as non-devolved functions: for all parts of the UK, thanks to the Sewel convention that provides for Westminster to legislate for devolved matters provided the devolved legislature consents, and as the only legislature for Wales until May 2007.

Albert Hirschman has compellingly showed, in a wide range of contexts, the importance of ‘voice’ – the sense that one can express views, and have them taken into account by decision-makers. But voice is important more because of what it is linked to than in itself. Views given voice can breed loyalty, and cement a damaged relationship, if those giving voice feel they have been heard and the organisation has responded, or at least sought to respond. If their views are rejected, the outcome is likely to be ‘exit’. In this context, the question is ‘what ensures that the voice is heard?’ For voice to breed loyalty would imply taking steps to ensure that the voice was heard at UK level, and had an influence there.

The constraints on divergence are important, however. They are partly financial (important as growth in public spending has slowed), partly legal and administrative (there are powers to block some devolved action, not just for exceeding devolved powers but for being contrary to various, mainly security-related, UK-wide interests), partly party-political. The overall impact, however, is that social and domestic policies vary, in ways that only make sense to those with a detailed knowledge of the constitutional and administrative framework of devolution. That is fine for academics and civil servants, but to the general public, journalists and indeed politicians outside government the reasons why some areas of government activity are devolved and others are not is not clear. The explanations are convoluted and technical, not rooted in general principles. A general consequence has been the haphazard fragmentation of a sense of UK-wide social citizenship, without any adequate replacement by Scottish, Welsh or English social citizenships instead.

Robert Hazell, in The English Question. says that the Conservatives look to rebalance the union - English votes on English laws - but are opposed to regional government. Labour thinks we need to devolve more, but regional assemblies didn’t happen when they were last in power. Having an English parliament gives us a federated state, but that would make England far too dominant, merely because of population. This, which will seem perverse to some, suggests that proportional representation is what we need, since this would reduce the disproportionate numbers of (Labour) MPs from Scotland and Wales.5

Regional government in England is the only solution which offers an answer to both versions of the English Question [giving England a stronger political voice; devolving power within England]. It could help to give England a louder voice within the Union; and it would help to decentralise the government of England. But defeat in the North East referendum has raised the bar. Any future proposals for elected regional assemblies would need to offer a stronger set of powers and functions, to show that they could make a difference.

I put a table copied from The English Question at the very foot of this webpage (mostly because I can’t format it correctly; I pasted to excel then saved as .pdf and it reproduces as an A4 shape). The table shows reaction to various possible suggestions and the reaction suggests to me that we have yet to appreciate what is possible, which in turn says that politics is failing - we are insufficiently interested in our own governance.

I am frustrated at not finding much dated 2014 telling me at length what is going on. The newspapers don’t give enough detail. If you can shed light, please do. Email me button is at the bottom of the page.

DJS 20150108

1 powers not devolved are vested in the UK government

2 Scotland has parliament not Assembly, so makes its own legislation.

3 Ireland’s government powers are divided as transferred, devolved and excepted. The excepted powers are listed by me as reserved.

4 Institute for Public Policy Research

5 I check here that MPs really do represent equal numbers. 650 MPs in 2010 meant around one per 100,000 people (bodies, not voters). Citing England Scotland Wales and NI in turn, numbers in 2010 were {533, 59, 40, 18} and a 2013 review (600MPs) suggests {502, 52, 30, 16}. Using the population figures I calculate below, {53.7, 5.5, 3.1, 1.8} the ratios are {0.107, 0.106, 0.103, 0.113} in millions per MP, pretty even.

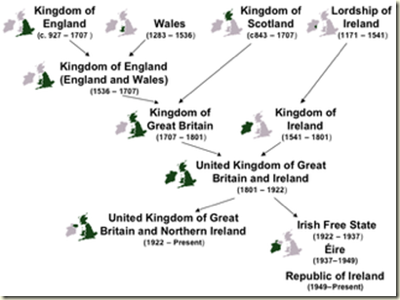

This diagram is destined for elsewhere:

These helpful explanations are from

Alan Trench’s blog pages.

The Barnett formula gives the devolved administrations a proportionate share of spending on ‘comparable’ functions in England, given their populations compared to England’s. The population proportions for 2011-14 (expressed as a percentage of the population of England) are:

Scotland 10.03 Wales 5.79 Northern Ireland 3.45 (so a total of 119.27%)

implying populations (in Millions) are: UK 64.1M, England 53.7M, Scotland 5.5M, Wales 3.1M N Ireland 1.8M

The Sewel convention provides that the UK Parliament may not legislate for devolved matters without the consent of the devolved legislature affected.

The West Lothian Question draws attention to the anomaly caused by asymmetric devolution, in which devolved legislatures have law-making powers for some parts of a country but the shared parliament is also solely responsible for government of part of the whole. In the UK, the anomaly arises because devolution is limited to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (which therefore each have two parliaments governing them), while England is governed solely from Westminster.

Websites used, hence further reading:

https://devolutionmatters.wordpress.com/devolution-the-basics/

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/election_2010/first_time_voter/8589835.stm

https://www.gov.uk/devolution-of-powers-to-scotland-wales-and-northern-ireland

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/implications-of-devolution-for-england

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/devolution.htm

http://www.amazon.co.uk/The-State-Nations-2008-Devolution/dp/1845401263

http://www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit/constitution-unit-news/161214

http://www.ucl.ac.uk/spp/publications/unit-publications/94.pdf

http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/10161/1/Your_region_your_choice_-_revitalising_the_English_regions.pdf

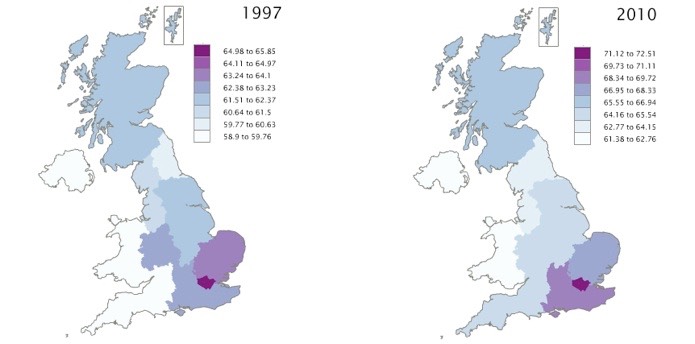

Below two maps showing regional share of total resources from GOS, MI and CoE, from here, the Office for National Statistics

These maps show the percentage of a region's total income (primary resources plus secondary resources) that was made up of the combined CoE, GOS and MI components in 1997 and 2010. [Gross Operating Surplus (GOS), Mixed Income (MI) and Compensation of Employees (CoE) These three components together make up the bulk of primary resources, which is the income earned by the household sector as a result of productive activity or the ownership of productive assets. They include wages and salaries, rental (imputed or otherwise) and income from self employment.] In 2010, of the 12 NUTS1 regions, London and the South East get the greatest proportion of their overall income from these components, at 72.5 per cent and 68.5 per cent respectively. Wales and Northern Ireland get the smallest proportion of their overall income from these components, at 61.3 per cent and 62.5 per cent respectively.