There is a rumbling occasionally reported in the press I so often denigrate reflecting an ongoing dispute over the ‘ownership’ of the South China Sea.

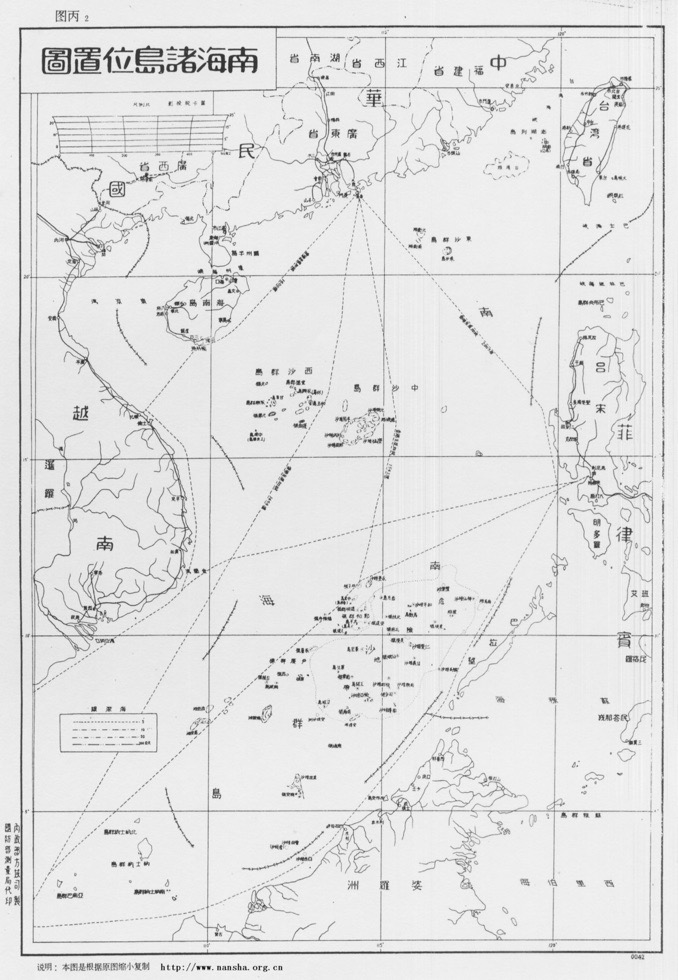

Way back in 1947, which is before the creation of the People’s Republic, there was a map, the eleven dash line (shown, black & white). This reflected a claim made (as far as I can tell, internally) and was subsequently taught in school, which means that there is a vast number of people who have been told “this is ours”.

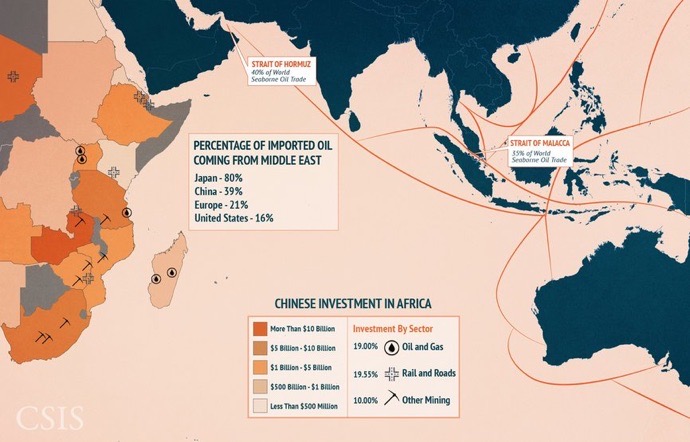

The South China Sea is bordered by China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Malaysia (Borneo, Sumatra and the peninsula), Brunei, Indonesia, Singapore, perhaps Cambodia (it depends how you define the space) and Vietnam. Along its bor-ders are the straits of Taiwan, Malacca and Karimata. One third of the world’s shipping crosses some part of this space.

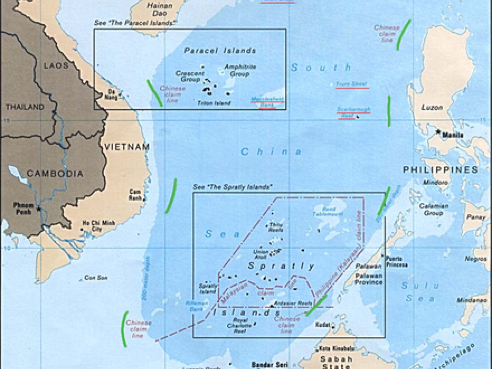

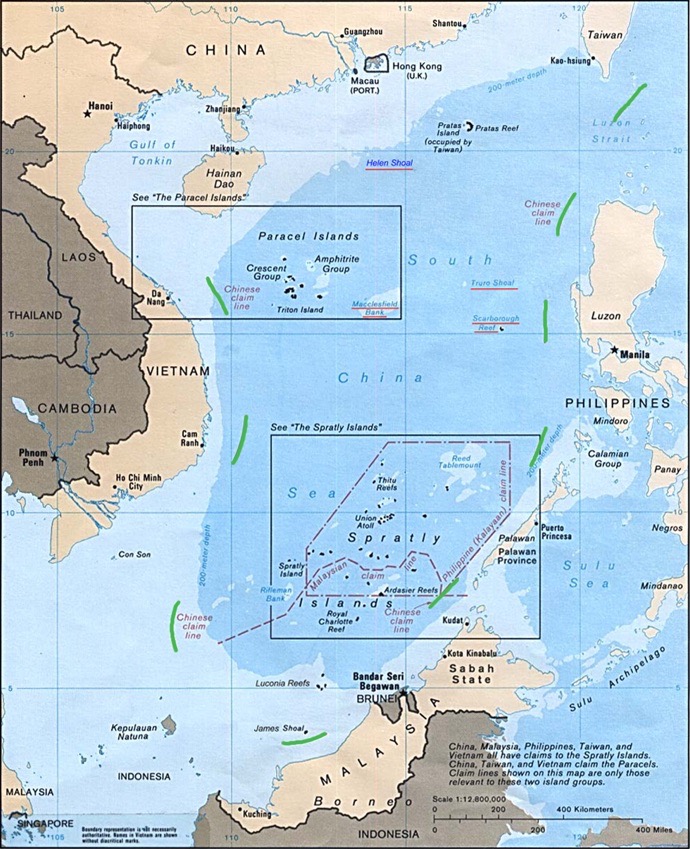

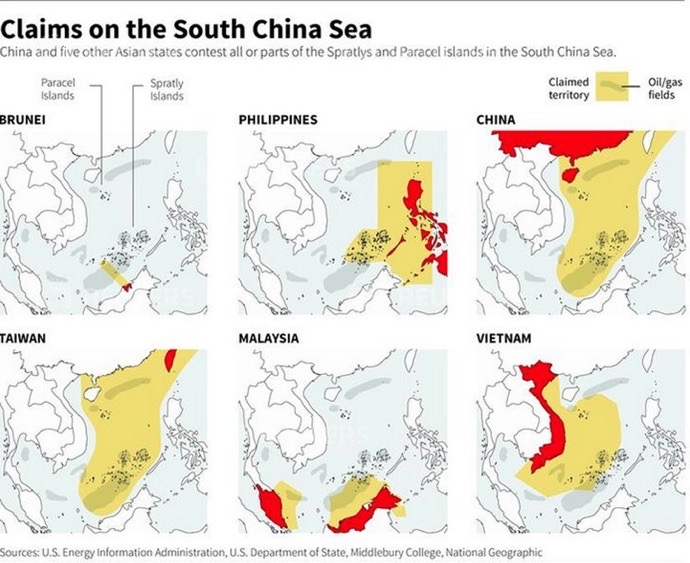

A domestic dispute as to the location of the Spratly islands revealed that we were both wrong and they are located far further south than either of us thought. Bearing in mind that the boss went through the Chinese geography course at school, she might be expected to know already about the nine (or ten or eleven) dash line. Here is a more usable map that allows one to recognise names from other sources.

It shows the ‘nine dash line’ and you might spend a little time looking for the differences.

The current issue is that these maps are the substance of the current claim by China to ownership of this tract (the ‘cow’s tongue’) of sea. Most especially the sea bottom, since there is a suggestion that we might expect there to be oil below. Since the sea is not particularly deep [evidence?] we might expect there to be ongoing exploration for oil deposits and, the moment there is evidence of volumes, we can expect the level of international disagreement to ramp up sharply.

China has been remiss in making claims under international law for this area1. In effect it has been rejecting that law. Meanwhile, the attrac-tion of available oil in an otherwise oil-starved region is encouraging several nations to be frantically building on the tiny reefs that poke above the sea surface.2

The low estimate of volume equates to what Norway has left under the north Sea, which is about half of what is left in total, where we have extracted more than half (the cheaper half). See Peak Oil.

Jeremy Maxie, writing in Forbes, tells us that this territorial dispute might well be as much about fishing as oil and gas, but underlying this is one of sovereignty. He says we have the argument back to front: China is not asserting expansive territorial claims and risking military confrontation with its neighbours (and potentially the United States) just to gain access and control of unproven oil and gas resources; instead, the development of offshore oil and gas resources is contested because it evokes sovereignty. I say this may be chicken and egg, but I do not entirely understand what this means nor how we should use that to understand China’s attitude.

There is dispute and confusion how much oil and gas there is in the South China Sea. I found estimates of 2 and 200 billion barrels easily. Quoting Forbes and Maxie: the U.S. Energy Information Agency (EIA) the South China Sea is thought to hold 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas (Tcf) including both proven (P90) and possible (P50) reserves. These high-end estimates are the most widely quoted, frequently without the caveat that it includes probable reserves which only have a 50% certainty of being recovered under existing economic and technological conditions. This misrepresentation adds to the misconceptions that drives the resource conflict narrative. Longer quote in footnote 3. In contrast, CNOOC claims that the SCS holds an estimated undiscovered 125 billion barrels of oil and 500 Tcf of natural gas.

To put these numbers in context, China’s annual demand is around 4 billion barrels; remember (Peak Oil) that it is the first half that is relatively easy (cheap) to recover, so the latter half is obviously expensive and therefore, as with closed mines, one must wait until the price goes up enough to make extraction of the latter half economically sensible.

One topic of agreement is that the SCS is mostly ‘gas-prone’, meaning there’s way more of that. China’s demand in 2015 was just under 7Tcf4. Quoting Mr Maxie again, this means that the total projected SCS gas reserve would meet 2015’s gas demand in China alone for 30 years.

I thought the SCS was shallow, but it is not; at 400-1200 m this is what the oil industry calls deep-water.

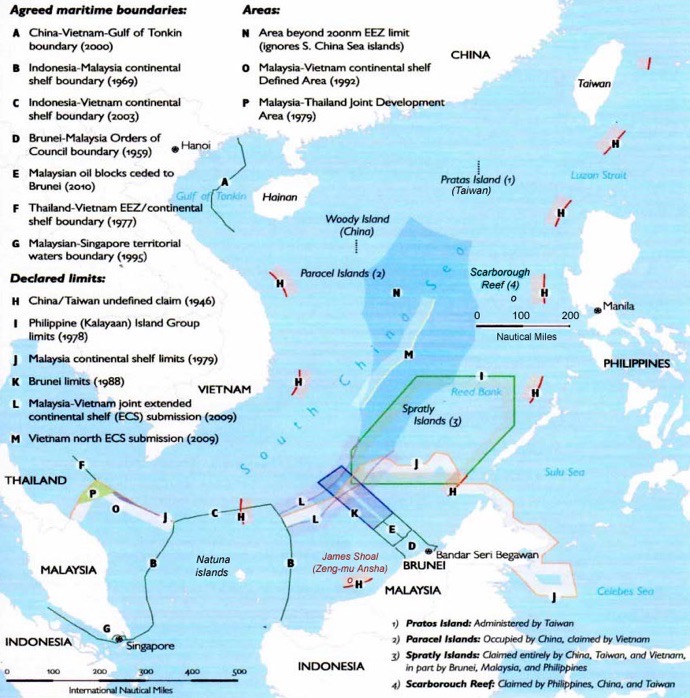

This mostly blue map goes some way to explaining which claims have any degree of agreement. It informs external statements as to ‘ownership’ of putative volumes of hydrocarbons. From the wikipedia entry.

From a different perspective, one I collected from Australia, we might look at the disruption that active dispute (warships in some aggressive mode) would have upon trade across the Pacific. This is mostly because of the traffic thro-ugh the straits of Malacca (Moluca, Meluka, etc).

The article that goes with this makes interesting reading.

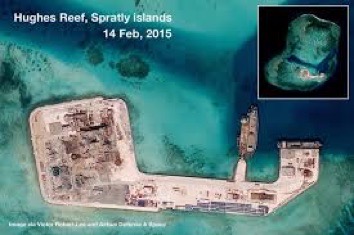

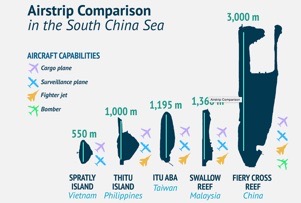

What is actually occurring in the SCS is that there is rapid building taking place. You can see quite a bit of this by playing with Google Earth. Several countries bordering the SCS (plus US interests, I suspect) have built processing or holding units for hydrocarbon extraction, various military installations and some runways. These last are actually the easiest to find for yourself.

:

In summary, I cannot separate the sovereignty issue from the pursuit of oil and gas, though maybe you can, in which case please explain that to me. To China alone the acquisition of the bulk of the anticipated field represents a gain similar to that of the north sea fields to the UK.

DJS 20170124

Happy birthday Hoagy

...and on the 25th, the Times had a lengthy article on the same topic.

wikipedia entry

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nine-Dash_Line

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Territorial_disputes_in_the_South_China_Sea

http://www.forbes.com/sites/timdaiss/2016/05/22/why-the-south-china-sea-has-more-oil-than-you-think/#b9ff6e43a3f8

http://www.businessinsider.com.au/why-the-south-china-sea-is-so-crucial-2015-2

Pictures of establishments in the SCS. I googled (images) for South China Sea installations, construction, airstrips.

1 Ruling at the Hague in dispute between the Philippines and China (the PRC) that China has no basis for ‘historic rights’. BBC link

2 A USGS survey of 1993 suggested there is a lot of oil down there. See Forbes. Estimates vary between 28 and 213 billion barrels, which is a large range. For context, the biggest in the north Sea, Clair field, is 8 billion barrels. 29 billion barrels is the same as what Norway has left under the North Sea, itself about half of what is left.

1 tonne of crude oil is 7.5 barrels

North Sea oil/gas is half gone: of what is left, Norway’s bit contains about half of that. Norway’s oil reserve at 2007 was 29 billion barrels.

3 Maxie said in Forbes: Estimates of oil and gas reserves vary since the SCS remains mostly under-explored with the majority of unproven reserves located in offshore deep-water areas. According to the U.S. Energy Information Agency (EIA) the South China Sea is thought to hold 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas (Tcf) including both proven (P90) and possible (P50) reserves. These high-end estimates are the most widely quoted, frequently without the caveat that it includes probable reserves which only have a 50% certainty of being recovered under existing economic and technological conditions. This misrepresentation adds to the misconceptions that drives the resource conflict narrative.

The EIA South China Sea report estimates Vietnam’s reserves at 3.0 billion barrels of liquids and 20 Tcf of natural gas, while China’s are at 1.3 billion barrels of liquids and 15 Tcf of natural gas. The Philippines’ share of reserves is only 0.2 billion barrels of liquids and 4.0 Tcf of natural gas. Malaysia has the biggest share, with 5.0 billion barrels of liquids and 80 Tcf natural gas, while Indonesia hold 55 Tcf of natural gas but only 0.3 billion barrels of liquids.

In contrast, CNOOC claims that the SCS holds an estimated undiscovered 125 billion barrels of oil and 500 Tcf of natural gas. These numbers are likely inflated for political purposes, as the consultancy Wood Mackenzie estimates that the SCS only holds about 2.5 billion barrels of oil equivalent. The focusing on estimated reserves of oil or natural gas is also misleading, as global average recovery rates for “oil in place” is only about 35% with technical limits estimated at 60-70% with enhanced oil recovery techniques.

4 Tcf, Trillions of cubic feet. Now there’s a stupid unit. 1 TCF = 28.3 billion cu. metres, meaning 2.83x1010m3, or 28.3 km3.

Islands I can name with construction on them include:

airstrips: Fiery Cross Reef, Swallow reef, Itu Aba, Thtu Island, Spratly Island, see map

Woody Island, Mischief Reef. Ayungin, Subi Reef, Johnson South Reef, Cuarteron Reef, Hughes reef,

There’s a display from the NYT worth watching. I found it some work to discover how to move it on to the next frame. A flick of a finger along (not across) my mouse proved the best action.

Response - I got one!!

Steve, who oscillates between the US and China, and who is a declared nihilist, said, 25/1/17:

South China Sea. Here is what is going on. Around 2002, the PRC military academy published a book on the projection of power. They looked at the world from 1600 and noted a succession of world hegemons: Portugal, Holland, Spain, France, England. They asked: why did each of these empire builders ultimately fail? The answer is that they spent so much money maintaining their empire that they ultimately bankrupted themselves.

Then they took up the question of China vs. the U.S. First, they concluded that China will never be a hegemon because China will never be wealthy enough to fund the enterprise. It is interesting that their logic was: in the modern world, for a nation to become rich, it must become a liberal democracy on the EU/North American model. China will never do that, so China will never acquire the wealth.

But what to do about the U.S.? The policy recommendation was to goad the U.S. into seeing China and a threat and through this to induce the U.S. into excessive spending on projection of power: armaments, troops and related. In connection with, induce the U.S. to hollow out domestic infrastructure spending while at the same time creating a police state atmosphere of constant fear. Based on the history of the other world hegemons, this should then ultimately bankrupt the U.S., removing from the world stage as a hegemon.

However, under this policy, China will NOT seek to replace the U.S. as the next hegemon. The fall of the U.S as hegemon will introduce a new system of a truly multi-polar world. Under this system, each regional hegemon will be constrained by its economic ability to project its power within its region.

So the South China Sea is part of a plan aimed at the U.S. So far, the plan is working well.