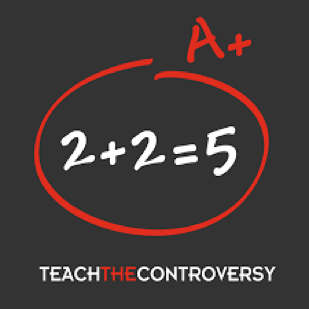

When I was writing about stupidity I was close to including a refusal to use mathematics. Where most of the time I mean arithmetic. I really do not understand why it is that we so readily accept that, for example, it is acceptable for someone in the public eye to say “I could never do maths” followed so often by a statement which illustrates a failure to make logical statements.

It could be that the habit of testing mathematical statements for truth, “This really is equal to that” never percolated. It could be that a failure at an early age to be satisfied with ‘getting things right’ leads to be happy not getting things right, as an expression of the status quo.

For those people who don’t know whether they fall into either camp, I’ll give some examples of cases where I think using maths would be appropriate:

- 1. Shopping at the supermarket and keen to underspend, you see Scotch Eggs at 30p each, 75p for two and £1 for 3. You want some, maybe three or four. What do you do?

- 2. A group walking on Dartmoor have a planned route for say 30km and, after two hours it is nine o’clock and they have covered 5km. When do they expect to finish?

- 3. You’re driving in a 20mph zone. You are expected to be able to stop in a short distance; standard tables suggest 40ft or about 13 metres. Assuming those conditions apply and that there may be circumstance in which you’d be expected to stop, how fast would you be going at the notional non-impact point if instead you were doing 26mph? Put it another way, how far beyond the expected stopping point would you actually stop?

- 4. A similar group on Dartmoor are not enjoying walking on wet heather in springtime. One of the group observes that they all walk faster when on any sort of track, including a sheep track. If they changed from going directly to their intended target and instead took the next available acceptable sheep trail, how far off the desired direction could they go and still be going faster in the desired direction? Try for a guess in multiples of five degrees before you go work it out.

- 1. The single eggs are significantly cheaper. I am not the only one to notice this. Why then do people choose the other offerings? Mostly because they don’t want to think about the numbers, I suggest.

- 2. Continuing at the same rate, they would expect to finish this route in twelve hours, ten more from noticing the time, so 19:00. Which, for many groups, means that they will not finish this route. Which in turn means that they have a problem that should have been addressed before they started. It is likely that they have (i) someone inexperienced added to the group who has a problem so that this has not been factored into the plan. If completing the route is important then (i) this needs to be communicated and there are consequences such as a late finish or someone dropping out or (iii) the route need to be modified to accommodate what today’s group can achieve. In a sense, it needs to be clear what it is that constitutes a success for the day. From experience, such a group would make far better time if they ceased stopping to regroup and found a speed that their slowest member can walk all day. Boring but true. I still do about 5kph on rough ground, but my stopping is under a minute an hour. But then I can (and do) do arithmetic. Incidentally, this was a fairly common problem at PMC and generally a 19:00 finish was okay, where a 21:00 finish was dubious and was often dealt with by abandoning that route, though our action rather depended upon the weather and which training weekend it was.

- 3. You are supposed to already know your stopping distances. It was easy in the bad old imperial days of miles and feet; for speed S mph, the total stopping distance was made up of thinking distance S feet plus braking distance of S2/20. At 20mph that is 20+400/20=40 feet. At 26mph you need 26+676/20=60 feet (a tad less) and, at. At the 40 foot mark you’d have been braking for 14 feet, so the speed at that instant would be whatever needs 26 feet to stop in, S2/20=26 or √(26x20)=23mph. At impact you’d STILL be over the speed limit. So why do you NOT obey the limit in a 20 zone?

- 4. Exciting, an excuse to use geometry. Say speed on the Dartmoor-standard rough stuff is R and about 3kph. Say speed on a sheep track is S and about 4kph. Differences of 0.5 to 1.0 kph are normal, based on a lot of observation by me. Bigger differences are possible, but once it is learned that this approach works, the calculations are moot (because it is now a strategy). Draw a right-angle triangle with the longest side S and the middle length side R. The cosine of the angle between these is R/S. For 3 and 4 we get an amazing 40º. For 3,5 and 3 we get 31º. For 5 and 4.5 we get 26º. In other words, you can look quite a long way ‘off-direction’ for any surface that will be quicker to walk on and that such a choice will succeed in comparison to plugging away at a compass direction. You don’t do this if working/walking in bad visibility. Most of us do open-ground walking in relatively nice weather. This simple calculation—once seen, it is not as if you’re going to refine it—shows that there will be gain a long way off target. Obviously you will need to compensate with another such track in a while, but this applies also to very short-term choices (i.e. within several paces) as it does to long stretches. I have noticed recently that on wet ground the ‘path’ is actually slower than using the ‘rough’; I am aware that on Lakeland hills, some stony paths are slower than the adjacent grass (now the policy is seen to be bad for one’s personal erosion coefficient). I also notice these states are significantly changed by the current degree of slope. The situation is similar but different if running.

Those examples barely use GCSE maths. What they require is a willingness to look at the numbers and see that there is a useful question to ask. You agree, I hope, that the maths above is pretty easy. My point is that such a question is too often not posed. What used to drive me to distraction (rage, wanting to be elsewhere) is not just the failure to recognise the message in the numbers, but (far more often) that there is a refusal to act in line with the result. A sort of “Yes, but this doesn’t apply to me”, which could be translated as really not caring at all.

On Dartmoor, where such evidence often results in simply recognising that “Today is going to be a long day”, these are non-dangerous results. The group will eventually learn that they go at <this speed> and that this means in turn a ‘day’ is <that long>. Eventually they will address underlying problems, all which could be classed as preparation (from being fitter, to having better kit, to having a lot less kit, to sharing the weight around to balance abilities, to picking better routes, to waking up to the challenge as a whole.

On the road, I find the ignorance of risk astonishing. I agree that frequently one is left wondering why a piece of road has a particular limit. I picked the 20mph zone deliberately, since there it is common for other users of pavement and road to act on the assumption that 20mph means a 40foot stopping distance, that is, typically young pedestrians learn that this is a ‘safe’ place to act in ways that elsewhere would be grossly irresponsible. We call this ‘safe’. Yet every day you drive through such a district you are aware of the significant numbers of road users that exceed the designated limit by so much that they would still be over the speed limit at the point of impact. It may be relevant to quote the African saying in translation “If you want to go quickly, travel alone; if you want to go far, travel together”. For long distance walks, the trick is to reduce the stopping to a minimum.

More advanced forms of these same questions:

- 31.Assuming you are aware that many people exceed the posted speed limit, then for speed limit L, at what expected stopping distance do you not only fail to stop in time but are still exceeding the posted speed limit? Does that inform your driving style? Might you use that to inform others? [Excuse for use of algebra, but the problem is not can you do that, but can you set up the algebra to be done, the difficult bit that goes first].

- 32.Speed vs Safety essay 156, uses the term marginal speed. If you have 10% excess over the posted limit, what is your residual speed at the point when you ‘should’ have stopped?

- 33.(and 2) If out walking on open ground, are you aware of your changes of speed? Of direction? Are you aware of the many micro-decisions you make that constitute such walking? How do you modify those choices with regard to what you can see? This might be asking you to assess your own capacity for use of feedback. Does it matter ho much you lift your feet in taking a step? Does that answer vary with the ground? if it does, do you use that information in making short-term route choices?

Oh, you complain, that’s not maths. well of course it isn’t: Maths is the tool for doing other stuff, rather like language is for communication.

I am sure that the hard parts are:

• recognising what would lend itself to such a problem. Indeed, often, recognising that there is a problem at all.

- • acquiring the data (but I note that very often the data is in front of us already, begging the question to be asked)

- • setting up the maths to be done. I often said to classes that the world doesn’t actually need very many super mathematicians. what is doe s need is a lot of people who recognise that there is a problem to pose and that these people be able to communicate what that problem is so that a solution can be found. And communicated back to those who are expected to make non-mathematical decisions based upon something better than an unexplained reaction.

Why do we do maths? Mostly because we need it to explain so many things. I am noticing increasingly a connection between an inability to explain (many things) and a low ability to do maths. Where perhaps what I mean is an ability to think in mathematical terms, for there are many people with an acceptable qualification in maths who persist in the refusal to apply any such thinking. it is one thing to fail to spot some possible mathematical application. It is entirely something less to deny the evidence and to refuse the result.

DJS 20160419

Happy birthday, JP

I resisted the inclination to use medical risks, though I am not entirely sure why. A rich field: perhaps I am open to suggestions. What would be appropriate?

What is the point in Maths? “A point has no size, but simply marks position. See Essay 31

See several other pages on this site, not all in Lower School Extension work:

31: Let L be the Limit, your fast speed is F, your stopping distance is supposed to be S2/20+S and in practice it is F2/20+F, so the difference in distance, ΔD, is L2/20. Multiplying all through by 20, we have

F2 -L2 +20(F-L) = L2 Rearranging, F2+20F = 2L2+20L = 100∂. Solving for F, F=10[√(∂+1)-1]. Giving:

L 20 30 40 50 60 70 mph

100∂ 12 24 40 60 84 112

F 26 40 64 68 82 96 mph

T 0 48 57 66 75 mph

T is that speed that leaves you doing 30 mph at the expected stopping point:

Let 100ß be defined as 900 + L2-20L; then T=10[√ß+1)-1] and we can add a row reading, T≥30.

Look what that means at motorway speeds!

32: Let L be the Limit, your speed is S=1.1*L, your stopping distance is supposed to be S2/20+S and in practice it is L2/20+L, so the difference in distance, ΔD, is (S2-L2/20 +(S-L) = (S-L)(S+L+20)/20. So your residual speed, R, is when R2/20 = that difference, so R2= (S-L)(S+L+20) = (0.1 L)(2.1L+20)

= 0.21 L2 + 2 L

L 20 30 40 50 60 70 mph

S 22 33 44 55 66 77 mph

ΔD 6 12 21 31 44 58 ft

R 11 16 20 25 30 34