The 2015 election and the Queen’s Speech that followed indicated an intent to repeal the Human Rights Act and to replace it with a British Bill of Rights. I find lots of text that doesn’t seem to tell me very much.

There are distinctions to be made between what the HRA says that’s good or bad, what we’re going to do about the HRA, what we want to do, what’s wrong with the situation. In the end I doubt we’ll end up doing anything – a small majority in Parliament means that it takes only a few people to zap any intention.

Michael Gove, recently made Justice Secretary, is the advocate for this change.

What the Government actually wants to do is in the content of the Queen’s Speech, from which I quote:

The Government will bring forward proposals for a Bill of Rights to replace the Human Rights Act. This would reform and modernise our human rights legal framework and restore common sense to the application of human rights laws. It would also protect existing rights, which are an essential part of a modern, democratic society, and better protect against abuse of the system and misuse of human rights laws.

So here we have an implication that something needs fixing. What needs fixing?

Part of the problem is a political one. The 1998 Act was brought in by the new Blair government as one of their key reforms. I quote Parnesh Sharma, who is something of an expert on the subject: ¹

It was a reflection of the times. The Act was introduced during a period of much soul-searching about the nature of British society and a perception of society rife with racism, social exclusion, and a deepening divide between the haves and have-nots. These very issues were being laid bare in the late 1990s by the then-ongoing public inquiry into the race-motivated murder of Stephen Lawrence and its scandal of uncaring authorities and bungled investigations. The Act was born of an ambitious hope that enhancing awareness of human rights would in turn result in a culture of rights, in a more inclusive, more caring Britain.

Relentless tabloid attacks and intemperate criticisms by its architects have ensured that many have come to see the Act as un-British – for creating a culture of entitlement, not of rights; for protecting the rights of criminals and outsiders at the expense of citizens. That the Act has done neither is beside the point.

Many want it to be limited in application if not outright repealed. And that includes Tony Blair, the person most responsible for its introduction.

The process of denigration started by Blair and Blunkett has continued under the Conservatives, who, to be fair, never supported the Act and had promised to repeal it when in opposition.

[It is] strange, though, how the Act should be seen as doing something which it has miserably failed to do: that is, offer real protection to the powerless and marginalised of society.

Toby Young, associate editor of The Spectator wrote on the topic in advance of the election: I quote in sequence but have taken out some content.

The fact that David Cameron has said he would like to repeal Labour’s Human Rights Act doesn’t mean he’s seeking to dis-apply the European convention. On the contrary, his proposal is to embody the convention in a British bill of rights. Nor is he arguing that the European Court should be completely disregarded. Rather, if the judges in Strasbourg rule that a particular British law is incompatible with the convention, that would be treated as advisory rather than binding under the new proposal. Whether to amend or repeal the law in question would be a matter for Parliament.

But if the convention will still apply, what guarantee is there that the British Supreme Court, whose judgements would be binding, will interpret it any differently to the European Court?

According to the document posted on the Conservative party website, some of the terms used in the convention ‘would benefit from a more precise definition’ so as to prevent them being given ‘an excessively broad meaning’. So the bill of rights wouldn’t simply reproduce the convention in every particular. Rather, it would seek to define the rights enshrined in the convention in a way that made it harder for left-wing jurists to impose their political views through the court. In short, the bill of rights would put a conservative [sic] spin on the convention.

Take Protocol 1, Article 2, for instance, which talks about the right of parents to educate children in accordance with their own religious beliefs. At present, that clause gives some protection to faith schools and a Labour government that sought to abolish them could be challenged in Strasbourg. But once the precedent has been set that it’s legitimate for Parliament to direct judges about how to interpret the convention, that protection begins to look more fragile.

For me, the biggest worry is that a country that is currently signed up to the convention, such as Russia, would cite the British government’s repeal of the Human Rights Act as an excuse to remove itself from the jurisdiction of the European Court.

In some ways. the comment that this article prompted is more revealing, in the sense that it brings other worries out of the woodwork. I observe that one imputes knowledge to contributors that may not belong. John Danzig ² took an active role. Among points made: it’s perceived as a good thing that we can take our government to court, preferably an international one (an essay topic if ever I saw one, just not for me). A suggestion that it would be interesting to see a single case where the issue of "rights" was invoked to defend a person associated with an unfashionable cause. I read many suggestions that any perceived retreat from human rights by Britain gives other countries an excuse to ignore them, followed by several saying "that’s not our problem"; UK activity has had little effect so far; selective signing and ignoring HRA is common (and the UK is accused of doing that too). Primary among the perceptions is that this move is seen as rejecting the European Convention – the UK being a pioneer of that, it would not be ‘a good thing’ for us to then be the first to discard it. This seems to me to be an ideal political target then – to be seen as not rejecting it but embracing it and improving upon it. That still does not indicate anything wrong with any of the Acts, beyond the political atmosphere as observed by Dr Sharma.

The original intent in the European Convention (or Court, or Contract or Council) on Human Rights came out of the end of World War ll reactions to two wars in close succession and with common enemies. The idea was to prevent such things happening again. Among the sovereign rights is that the people of a country have the right to determine how they run their country. Churchill called for this, ³ with the Council of Europe being discussed at length in 1948 and combining intergovernmental and inter-parliamentary structures, an idea then copied. The Council came into being in 1949, the Treaty of London and now includes all the European states but the Vatican, Belarus and Kazakhstan. ⁴

The Mirror [not a paper I usually take or even take seriously, but perhaps I should] makes some essential points:

1. European Convention of Human Rights ≠ European Union

The very first thing you need to know about the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) is that it has nothing to do with the European Union. The ECHR is not a EU treaty and membership of the EU does not formally require us to be signatories.

2. It is in fact UK judges who are responsible for interpreting the ECHR

Again, the EU has absolutely NO ROLE in this. The European Union would rather have its member states guarantee the protection of human rights as enshrined in the ECHR. But there still isn't a legal link. Glad we cleared that up.

3. Winston Churchill brought us into the ECHR

The ECHR may not have much to do with the EU but is related to the Council of Europe which oversees the ECHR.

The Council of Europe—founded after the Second World War—has 47 member states and we are one of its founding members. Any one member state can bring a case against a fellow Council of Europe state if it believes that state is violating the ECHR. The court's rulings are legally binding and the Council of Europe can check to see if their rulings are being observed. Belarus is the only European state not a signatory.

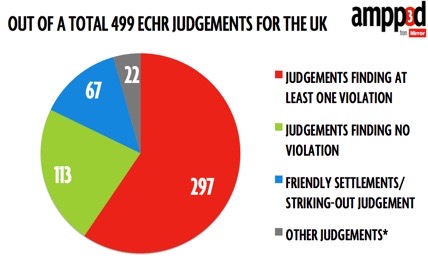

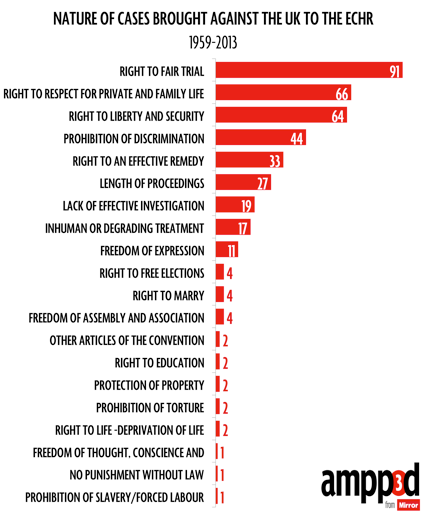

4. Since 1959 the ECHR [change of meaning; this is the Court, not the Convention] delivered the UK with less [they mean fewer; you can’t have half a ruling] than 500 rulings [whatever that 500 means; is that good or bad?]

Source: ECHR

And up to the right is how the judges of Strasbourg ruled:

Source: ECHR

5. The UK was found in violation in 60% of cases.

It might look like we are sore losers in that court but it's important to note that the UK is comparatively less unsuccessful than many of its European counterparts.

The average proportion of judgements lost across all the European countries: 83%. The average is considerably brought up by five serial violators: Russia, Turkey, Romania, Ukraine and Hungary.

6. How it's helped gay people, Thalidomide victims and innocent children. [I hate that unnecessary adjective; they’re kids; that’s enough.]

In 1979 the ECHR ruled against an injunction imposed on the Sunday Times which prevented them reporting on the thalidomide scandal.

When the Republic of Ireland banned homosexuality in 1981, the ECHR challenged this under Article 8, the right to respect for private and family life.

The same happened when our armed forces were dismissing homosexuals from armed forces after investigating their private life.

In 1986 the ECHR ruled in favour of trans* people allowing them to change their legal gender.

In 1998 the ECHR ruled against the UK government for failing to protect a child who was being beaten by their [its, surely?] stepfather.

In 2008 the ECHR ruled against the police storing the DNA and fingerprints of innocent people on their database.

in 2010 a government scheme which charged some immigrants a fee only if they were not planning to marry in the Church of England was ruled against.

Recently, the Bureau of Investigative Journalists filed a case challenging the UK Government over the police snooping of journalists' phone records through RIPA.

[Source: House of Commons Library, ECHR]

Let’s clear up an issue: the Court, ECtHR, was established by the Convention, ECHR. It is in Strasbourg, that’s a bit of France near (on, really) the German border, close to Switzerland (Basle, 135km). Judges sit for nine years, and number the same as the contracting states – which does not mean that each state has a single judge; each state offers three judges for consideration by the Council of Europe, the parliamentary assembly. It, the ECtHR, is distinct from the European Court of Justice, ECJ, [based in Luxembourg, one judge per (28) member state], but confusion is understandable, since the ECJ takes the case-law of the ECtHR to be part of the EU legal system. There are exceptions (which makes life interesting). Issues with all this centre around the ECJ acting as equivalent to the US Supreme Court, which upsets member states when they perceive interference – understandable. The most telling criticism occurs when the court expands the Treaty beyond its intents and when it appears to impose uniform rules across the Union. The feeling is that ‘local rules apply’ (far?) more often than the ECJ accepts. The ECJ is the highest court for Union law, not national law and I think this is the issue. The ECJ exists to (i) interpret EU law and (ii) to ensure its equal application across member states. So proper use is for national courts to request judgment and then to decide (locally, nationally) how to apply those judgments. Taking action on any failure to act is not the direct responsibility of the ECJ – they need to be directed to (told to, called upon) do so.

Am I any nearer discovering what is wrong with the ECHR (Convention)? Not really. I wonder if really the UK needs to rewrite the UK’s 1998 Act. Nothing persuades me that this is wrong.

The first point below may explain most of the British reaction. From the Guardian;

Part of Britain's attitude can be explained simply by a different conception of the law. In continental Europe, judges—guardians of written constitutions—routinely overrule politicians. In the UK, parliament rules: primary legislation cannot be questioned by judges.

This may explain a good deal of the British reaction. We do not surrender the law to a minority of judges, however experienced; we use our representative MPs for this. Perhaps if we had a written constitution we, too, would have judges over-ruling Parliament.

Partly too, it stems from a few high-profile recent cases that have not gone the government's way: the court's initial refusal, for example, to allow the deportation to Jordan of Abu Qatada, and its insistence that it is wrong to deny all prisoners, in every circumstance, a right to vote.

Point two: it is a principle of UK law that prisoners serving custodial sentences lose the right to vote. See this. People in jail are legally (in UK law) prevented from exercising their vote. The ECtHR ruled that we are wrong to do so. Yet this is (very) long established law for us. ⁶ By the ECtHR telling us that one of our longest lasting principles is wrong, the collective reaction will understandably include an element of pram-tossing. Hence the deep-seated reaction that says “You can’t tell us that”.

Mainly, though, Britain's current attitude seems to be informed most strongly by the wider problems of its relationship with Europe, and the belief among many Conservatives that loudly defending "British sovereignty" and attacking all things European will not lose them any votes. Essentially, in other words, it is political.

Oh dear. Is that the sound of a politician making noise safely? A Eurorant? Do such folk really want us out?

Only Britain objects so strongly to a small number of ECHR rulings that it is contemplating pulling out of the convention altogether – and engaging at the same time in what many in Strasbourg, including senior British officials, see as a deliberate and often dishonest campaign against the court.

A point, certainly. There are indeed very few rulings that censure the UK. Many of these (if you can have many from few) are placed by people in detention of one sort or another. Headlines make the issues bigger than I think they are. For example, the stewardess with a crucifix has two issues; the effect upon the customer and hence on her employer’s business, and the separate issue that she refused to see this as a customer-relations problems. There too, her employer has issues with symbols and how they may be perceived by customers. I think this was a wrong issue that needed airing. I’m sure that vetting staff has changed to ensure it doesn’t happen again.⁸

As for the spying issue, I’ve been mildly surprised how many approve of Spooks-style activity that grabs whatever is available to defend our shores. Quis custodiet ipsos custodes surely applies too, but I for one don’t want that supervision offshore.

Last month, for the first time, the ECHR publicly expressed its concern about "frequent misrepresentation" and "seriously misleading" British press reports of its activities. Clare Ovey, head of the UK case-processing division, points out that of the 2,082 complaints against the UK dealt with last year, the court rejected 2,047 as inadmissible. It found no violation in 23, and upheld 12 – just 0.6% of the total. [But a third of the valid cases.]

Of the 2,500-odd potentially admissible cases pending against the UK, she adds, nearly 2,300 concern prisoners' voting rights (the remainder mainly involve the undue retention of DNA samples and criminal records data, expulsion cases, notably to Iraq, and complaints about indeterminate sentences).

True, a relatively high proportion of UK applications are by people convicted of a crime, but that's "mainly because Britain is an advanced democracy, where fundamental rights are largely respected. Other countries are not so lucky; there, this court plays a huge role in simply ensuring the rule of law is applied."

And whatever impression British newspapers may create, UK cases are not confined to criminals and terrorists: former Formula One boss Max Mosley saw his privacy complaint rejected; BA employee Nadia Eweida, who wanted to wear her crucifix at work, went home happy.

"This court has made so many positive UK judgments," says Ovey. "On press freedom, surveillance, deaths in police custody, admission of evidence, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender rights, corporal punishment in schools, protection of children … It is worrying, when you see that it is so misrepresented."

The court's determinedly anglophile president, Luxembourg judge Dean Spielmann, is diplomatic but plainly concerned. Far from exporting European values to Britain, he points out, the court has helped import British values to Europe.

You know what? I conclude that not only is this a political issue or non-issue, but that there is another problem. Even as the Guardian explains what is going on, if it can accurately record the press itself as making frequent misrepresentation and misleading the public then the problem lies within the fifth estate.

The Press is, yet again, the enemy.

The scare-mongering occurs when, for example, the idea of having our own bill of rights better than the 1998 Act is interpreted as requiring us to reject the ECHR. The words frequently used are that this would ‘replace’ the Human Rights Act. That’s not the ECHR, the convention, but the Act from 1998. Why do we think we read differently? What I have read recently persistently leaves one with the message that it is the ECHR that will be abandoned – and I do not see why. Yes, if everything was on the table and likely to be rejected, that would be a consequence, but this is a relatively grown-up country and we are far more likely to find ways to strengthen a lot of the ECHR. What is on offer is an opportunity to better define some bits of it. I’m sure there are busloads of lawyers and politicians eager to put right things they feel wrong.

In PinkNews we have a typical example of the scare-mongering I refer to:

Article 14 of the Human Rights Act, which affords protection from discrimination, has been used in many legal cases to argue for protection for LGBT people. Liberty and other campaign groups are calling on Parliament to save the Human Rights Act.

Now, this doesn’t say directly, but implies wonderfully, that all LGBT people and their supporters (the readership) should be worried that all the progress made in improving their situation is at risk. Why do we get that impression? Is it deliberate? How is it that the words are right but the message received is different? Are we unable to read? Really? Did you read 'Human Rights Act' and think 'European convention'? Why? How were you bamboozled into that?

Surely the message in the UK is actually the opposite of a reason to panic; if the legal situation has been made clear then we do not have a habit of changing such things. We repeal Acts of Parliament, not legal decisions. We do that when we agree we have bad law, which usually means the law of unintended consequences has applied itself, care of Mr Murphy. Staying with LGBT affairs, the changes we have made reflect the changing opinions within the country (and think of Eire’s referendum result) and we do not elect MPs to disagree with their constituents (even when they do just that). We should expect any discussion of a GB version of the ECHR to represent, generally, something stronger, not weaker. There will be areas covered by the convention and especially its interpretations from Strasbourg (not Luxembourg) where our very Britishness demands something the ECtHR disagrees with, and prisoners’ rights falls into such a category (not necessarily all such rights, I didn’t say that, but I’m thinking disenfranchisement is too far). I can see the perceived need to reduce far further the incidence of events where uk.gov is declared to be ‘wrong’ and I can see that as a nation we need a way of marking our territory, so that we are not seen to be ruled by anyone outside Britain. That, it would seem to me, is as far as most of the country wants to be ‘in’ Europe. I would hope that all those politicians we didn’t vote for [see essay 167] are able to explore what their constituents really want the end result to be. I pray they can be intelligent, though en masse they too often appear not to be.

I still don’t know what’s wrong with the European Convention on Human Rights. Nor, for that matter, with the 1998 Act. Looking in wikipedia I found ⁹ a criticism copied below and in the other reading I did I saw that what is supposed to happen when the ECHR conflicts with other British law is that our justice system reports a problem, a declaration of incompatibility. This idea is supposed to preserve Parliamentary sovereignty. I can’t find any that have been made, though I did find complaint that British judges have twisted language in trying to square a circle. If the proposed Bill was to break the connection with the ECHR, we’d simply have more UK cases going to Strasbourg, and I suspect that at that point we’d find that the UK took every Strasbourg decision as advisory. I treat suggestions that we’d opt out of the ECHR as merely statements of how strongly we feel about having external control of our nation. The comment section from the Independent (some of which is more worthy of the NEWS Thump) wonders whether all of this fuss is really about controlling terrorism. Some of the sections need a sensible rewrite in the light of experience. I began to wonder how much of the content was a delayed reaction to what is now seen as the ‘me-me-me’ of the Thatcher years, though that was not what it felt like at the time. I also wonder if, in the pendulum swinging a little the other way, whether we might have the odd sentence making it some sort of duty to be conscious of the needs of society. Edging towards the needs of the many, perhaps, but if all our government agencies must act in the interest of society at large, keeping it and its individuals safe, is there not then a case for each citizen to behave similarly? Do we have a right to expect our neighbour to behave reasonably? Do I see a worm in that can, or merely a fish in a barrel?

This could go on far more, as will no doubt the fuss over the proposed Bill, whether or not it succeeds. I predict right now that it’ll be put on indefinite hold and only come to light in the next Conservative government, whenever that might be. Meanwhile, having the conversation is not only useful, it may be sufficient for us all to come to grips with the situation. It may even affect how we tick a box in response to the inevitably tortuous question in the referendum we have been promised. Though I’ve always called a promise-that-isn’t-liked a threat, since that seems more honest.

DJS 20150529

How close is the existing HRA to a British Bill of Rights?

Re-readng this in 2020, I'm struck by the last ten or so lines, so easily transferred to 'now'.

http://news.sky.com/story/1490875/human-rights-act-what-you-need-to-know

The ECHR itself: http://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Convention_ENG.pdf

wikipedia on ECHR: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Court_of_Human_Rights

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Convention_on_Human_Rights

http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/ampp3d/six-things-you-should-know-4370967

http://www.theguardian.com/law/2013/dec/22/britain-european-court-human-rights

http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN01764

http://www.channel4.com/news/human-rights-european-court-forced-uk-rulings

http://news.sky.com/story/1491262/queens-speech-pm-backs-off-on-human-rights

http://www.pinknews.co.uk/2015/05/27/david-cameron-delays-plans-to-scrap-the-human-rights-act/

https://www.justice.gov.uk/downloads/human-rights/act-studyguide.pdf

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_Rights_Act_1998 Read the Criticism section at 9.

1 Dr Parnesh Sharma is the author of The Human Rights Act and the Assault on Liberty: Rights and Asylum in the UK, published by Nottingham University Press.

In the article I quoted Dr Sharma points to the Asylum Act 2002:

Even though the [Human Rights] Act has done little to protect asylum-seekers against ill-liberal policies, it has been primarily in asylum (and a few high-profile terrorist cases) that the Act has come a cropper. It hasn't really offered much protection but that hasn't stopped the right-wing media and politicians from laying waste to it – mostly because those seen 'winning' human rights claims are generally viewed as 'cheats' and worse.

The dominant narrative in asylum is almost exclusively about undeserving outsiders, and that the UK has lost control of its borders and is being 'swamped' by 'bogus refugees'. The blame for this apparent calamitous turn of events has been put squarely on the Act. As a former leader of the Conservatives wrote: Britain is being "taken for a ride" (by asylum-seekers) and "we are at the end of our tether".

A look back at the events of 2002-2005, precipitated by a surge of upwards of 90,000 asylum applications, offers some insight. That is when Labour introduced a rather odious piece of legislation, Section 55 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 was aimed at deterring asylum-seekers from entering the UK and encouraging those already here to leave voluntarily. The means chosen, however, had the effect of forcing thousands of asylum-seekers into destitution. And it was deliberate.

Section 55 became law by a sleight of hand – as a last-minute amendment to a bill already before the House of Commons. When questions were raised about its human rights implications, the ever dismissive Blunkett, then home secretary, guillotined debate in parliament. Liberty, the Refugee Council, and other organisations almost immediately recognised the intent and danger posed by the legislation and, with the Human Rights Act in hand, challenged the policy in courts. After a long and bruising three-year battle they emerged victors, much to the anger of Labour and Blunkett, who was described by the tabloids as 'spitting blood' in fury at the courts.

This hard-fought victory should have been a happy result for human rights advocates, but it has not been so.

True, the victory provided respite for destitute asylum-seekers, but the situation for them today remains pretty much the same. The get-tough measures and ill-treatment of asylum-seekers continues. In this and other respects the Act has not lived up to expectations. It has failed to deliver.

I point to the Queen’s Speech, in the section on immigration

Appeals: Extend the principle of “deport first, appeal later” from just criminal cases, to all immigration cases. In 2014 the last government cut the number of appeal rights but other than foreign criminals, migrants retain an in-country right of appeal against the refusal of a human rights claim. We will now extend the “deport first, appeal later” principle to all cases, except where it will cause serious harm.

I don't follow that last paragraph at all.

2 John Danzig is a journalist with a passion for human rights. In one of several contributions to the commentary in the Spectator, he wrote:

It is useful to understand some of the issues our Human Rights Act has helped to resolve; yes, not WWII type abuses, but I think very important matters nonetheless.

•Held the police to account for failing to investigate rape and human trafficking.

•Compensation for minors who were abused but ignored by social services.

•Upheld the rights of children to express their religious faith.

•Supported families fleeing domestic violence.

•Ensured the right to access to life-saving drugs on the NHS.

•Held hospitals to account when lapses in mental-health treatment have resulted in suicide.

•Given same-sex partners the equivalent rights and status as heterosexuals.

•Ensured that inquiries into civilian deaths in Iraq at the hands of British troops have been independent.

•Used to establish that failure to properly to equip British soldiers is a breach of their rights.

•Stopped councils from misusing CCTV surveillance.

•Used against councils who have closed libraries.

•Stopped Councils that have bypassed the rights of the disabled and the elderly.

This list struck me as things we should have covered elsewhere and already, but what do I know?

3 Wikipedia. In a speech at the University of Zurich on 19 September 1946, Sir Winston Churchill called for a "kind of United States of Europe" and the creation of a Council of Europe.[2][3] He had spoken of a Council of Europe as early as 1943 in a radio broadcast.[2]. He refers to this need throughout his memoirs of WWll, which six volumes I read in the early part of 2015.

4 Silly. Kazakhstan is not in Europe, being east of the Black Sea - and the Red and the Caspian. Other states perhaps not included are those of ‘limited recognition’ which in Europe (west of the Urals and the Bosphorus, north of Africa) means places ‘not recognised’ by at least one UN member, which includes Armenia (Pakistan rejects them), Cyprus (Turkey and vice versa on the island), Kosovo, (Serbia) and remaining problems in Moldova. If you think Azerbaijan and Georgia are in Europe, they continue to have Balkan-type issues.

I looked at definitions of Europe The sixth largest continent, separated from the rest of the Eurasian land mass (of which it forms the western part) by the Ural Mountains, the Caspian Sea, the Caucasus Mountains, the Black Sea, the Dardanelles, and the Aegean Sea. [free dictionary]

Wikipedia points out that Cyprus, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia are in the Middle East according to the World Fact Book and the UN Stats Dept., but that the Council of Europe deemed them all within the region. The European Union continues to encourage Turkey to join. Coloured green here is a region including European Russia but not Kazakhstan, excluding Turkey (and therefore Cyprus) and Georgia and Azerbaijan. I found many maps of Europe that ignore Russia. The Lonely Planet includes Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia but rejects Russia and Turkey. And Norway, Sweden and Finland; there’s a tale to tell, perhaps.

Geographically I want to draw the line down the Urals, to the Caspian and along the Caucasus. That puts the former Soviet states of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan outside. To bring them inside and with Turkey, we draw the line in the Caspian and cut west towards Cyprus. That keeps Kazakhstan and the rest of the Middle East out. Alternatively, draw the European border from the Urals and down the Volga, through the Bosphorus and into the Aegean.

5 From the ECHR, via the Guardian, link. Nice quotes from here: the Strasbourg-based ECHR could reasonably lay claim to being one of the most maligned institutions in Britain. ("Hardly surprising, I suppose," quips a senior British court official. "Our name contains the words 'European' and 'human rights'. Not exactly a winning combination.")

British judge Paul Mahoney: “At the end of the day, it's possible for somebody from a tiny village to come here, take their government to court and get the law changed. That really is a small miracle."

"We've been called a lot of things," Reid says. "The European committee for the prevention of human rights, scum of the earth … But we've also been asked to legalise cannabis. And declare an independent kingdom of Sussex."

6 To vote in a UK general election a person must be registered to vote and also:

be 18 years of age or over on polling day

be a British citizen, a qualifying Commonwealth citizen or a citizen of the Republic of Ireland

not be subject to any legal incapacity to vote

Additionally, the following cannot vote in a UK general election:

members of the House of Lords (although they can vote at elections to local authorities, devolved legislatures and the European Parliament)

EU citizens resident in the UK (although they can vote at elections to local authorities, devolved legislatures and the European Parliament)

anyone other than British, Irish and qualifying Commonwealth citizens

convicted persons detained in pursuance of their sentences (though remand prisoners, unconvicted prisoners and civil prisoners can vote if they are on the electoral register)

anyone found guilty within the previous five years of corrupt or illegal practices in connection with an election.

The principle of disenfranchisement came to us with democracy (What did the Romans do for us?), on the line of thinking that said disenfranchisement followed the loss of rights as a citizen – effectively civic death. In the US you don’t get this back after serving your sentence; well over 5 million can’t vote there, 10% of some communities. In the UK you get the right back when you’ve served your time.

7 Channel 4 gives six ‘key rulings’

Abu Qatada

In January 2012, the ECHR blocked the deportation of radical cleric Abu Qatada to Jordan, because of fears that evidence obtained under torture would be used against him in his home country. The extremist preacher had been found not guilty of terrorism offences after an eight year legal battle. The ruling, based on the right to a fair trial, was slammed as "completely unacceptable" by David Cameron and forced Home Secretary Theresa May to agree a new treaty with Jordan, guaranteeing him a free trial. This eventually convinced the court to allow his deportation in July 2013. Read more: Could the UK leave the human rights treaty over Qatada?

Prisoners' vote

In 2005, the ECHR ruled that banning prisoners from voting - in the UK and in other countries - was a breach of their human rights and unlawful. Mr Cameron responded by saying that the idea of prisoners voting made him feel "physically ill", and parliament has so far resisted implementing the ruling. Which raises one puzzling point: although member states are supposed to be obliged to stick to ECHR rulings, they can apparently resist and appeal. This is currently happening in Ireland, where parliament is resisting calls from the ECHR to revise its abortion law which it said treated women as "a vessel, nothing more".

Gay rights

Back in October 1981, the ECHR decriminalised male gay sex in Northern Ireland as a result of a case brought by Jeff Dudgeon, who was interrogated about his sexual behaviour by the Royal Ulster Constabulary police force.

More recently, in January 2013, the ECHR ruled against two British Christians who claimed that they were fired because they would not work with gay couples. Lillian Ladele, a marriage registrar for London's Islington Borough Council, and Gary McFarlane, a relationship counsellor, who refused to give sex advice to gay couples, lost their anti-discrimination case. Now, one suspects, rendered irrelevant by the referendum this month.

Religious discrimination

During the same ruling, the ECHR ruled in favour of Nadia Eweida, 60, who took her employer British Airways to court for forcing her to stop wearing a cross around her neck. Lawyers for the government, which contested the claim, argued that her right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion had not been violated. But ECHR judges disagreed by five votes to two.

Whole-life sentences

Another controversial ruling from July last year regards dishing out whole life sentences to prisoners and stems from a case brought by three multiple murderers, including Jeremy Bamber. Judges ruled that that a whole-life tariff breached article 3 of the convention, which prohibits torture. QC Peter Weatherby, who represented the three prisoners, said that even if prisoners are never released, "They should not have all prospect of future release taken away at the outset of their sentence".

In practice, this means that prisoners should be entitled to a review at some point in their sentence, and the possibility of parole if they have reformed.

Government spying

Three campaign groups have filed papers against GCHQ, accusing the British spy agency of breaching the privacy of millions of people in the UK and throughout Europe. The legal challenge came in the wake of revelations from whistleblower Edward Snowden about mass surveillance by the UK and US governments. The case is still going through the courts, but it is just another example of the kind of cases brought to the ECHR by the UK.

8 A visa condition in China is that you do no religious proselytisation. I caught a visitor doing that and interfered, because it risked the existence of the Centre. You have a right, in my view, to risk your own visa renewal but you do not have the right to risk mine or those of my staff. I’d far rather you kept your religious views to yourself. By all means question, by all means cause people to think but telling them opinion as fact or faith / belief as incontrovertible is unacceptable. Discuss at will.

9 there’s some well-written criticism of the 1998 Act on wikipedia

From the Conservative right[edit]

During the campaign for the 2005 parliamentary elections the Conservatives under Michael Howard declared their intention to "overhaul or scrap" the Human Rights Act. According to him "the time had come to liberate the nation from the avalanche of political correctness, costly litigation, feeble justice, and culture of compensation running riot in Britain today and warning that the politically correct regime ushered in by Labour's enthusiastic adoption of human rights legislation has turned the age-old principle of fairness on its head".[35]

He cited a number of examples of how, in his opinion, the Human Rights Act had failed: "the schoolboy arsonist allowed back into the classroom because enforcing discipline apparently denied his right to education; the convicted rapist given £4000 compensation because his second appeal was delayed; the burglar given taxpayers' money to sue the man whose house he broke into; travellers who thumb their nose at the law allowed to stay on green belt sites they have occupied in defiance of planning laws".[36][37]

The schoolboy referred to by Mr Howard was suing for compensation, not to be allowed back into the classroom, since he was already a university student at the time of the court case.[38] In addition, the claim was rejected.[39]

Politicised judges?[edit]

The Human Rights Act prior to its introduction, it would result in unelected judges making substantive judgments about government policies and "legislating" in their amendments to the common law resulting in a usurpation of Parliament's legislative supremacy and an expansion of the UK courts' justiciability. R (on the application of Daly) v Secretary of State for the Home Department highlights how the introduction of a proportionality test borrowed from ECtHR jurisprudence has allowed a greater scrutiny of the substantive merits of a government's policy, meaning that judicial review has become more of an appeal than a review.

The interpretative obligation under section 3(1) of the Human Rights Act to read primary legislation as Convention compliant, so far as is possible, is not dependent upon the presence of ambiguity in legislation.[40] Section 3(1) could require the court to depart from the unambiguous meaning that legislation would otherwise bear subject to the constraint that this modified interpretation must be one “possible” interpretation of the legislation.[41] Paul Craig argues that this results in the courts adopting linguistically strained interpretations instead of issuing declarations of incompatibility.

Journalistic freedom[edit]

In 2008 the editor of the Daily Mail criticised the Human Rights Act for allowing, in effect, a right to privacy at English law despite the fact that Parliament has not passed such legislation. Paul Dacre was in fact referring to the indirect horizontal effect of the Human Rights Act on the doctrine of breach of confidence which has moved English law closer towards a common law right to privacy.[42] In response the Lord Chancellor Lord Falconer stated that the Human Rights Act had been passed by Parliament, that people's private lives needed protection and that the judge in the case had interpreted relevant authorities correctly.[43]

A Bill of Rights for Britain?[edit]

Following controversial rulings from both the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom,[44] David Cameron again suggested a British Bill of Rights.[45] The government commission set up to investigate the case for a Bill of Rights had a split of opinion.[46]

Howard's successor as Leader of the Opposition, David Cameron, vowed to repeal the Human Rights Act if he was elected, instead replacing it with a 'Bill of Rights' for Britain.[47] Following the 2010 general election, the Conservative – Liberal Democrat Coalition Agreement says that the issue will be investigated.[48]

In 2007, the human rights organisation JUSTICE released a discussion paper entitled A Bill of Rights for Britain?, examining the case for updating the Human Rights Act with an entrenched bill.[49]

In 2013 Judge Dean Spielmann, the President of ECtHR, warned that the United Kingdom could not withdraw from the Convention on Human Rights without jeopardising its membership of the European Union.[50]

Left-wing criticism[edit]

In contrast, some have argued that the Human Rights Act does not give adequate protection to rights because of the ability for the government to derogate from Convention rights under article 15 especially in relation to terrorism legislation. Recent cases such as R (ProLife Alliance) v. BBC [2002] EWCA Civ 297 have been decided in reference to common law rights rather than statutory rights leading to the possibility of judicial activism.[51]

Terrorism[edit]

Senior Labour politicians have criticised the Human Rights Act and the willingness of the judiciary to invoke declarations on incompatibility against terrorism legislation. Former Home Secretary Dr John Reid argued that the Human Rights Act was hampering the fight against global terrorism in regard to controversial control orders:

"There is a very serious threat – and I am the first to admit that the means we have of fighting it are so inadequate that we are fighting with one arm tied behind our backs. So I hope when we bring forward proposals in the next few weeks that we will have a little less party politics and a little more support for national security.” [52]