Following on directly from the resource curse, I wondered, while reading and writing about that, if the same general scenario applies to other parts of the economy. To my surprise, I found an immediate positive, in Britain’s financial institutions.

We have been told repeatedly that the financial sector in London is the jewel in our economy. It attracts our brightest and best to the glitter of vast incomes; it raises the economy of the capital enormously by clearly bringing in loads of income from abroad; the spin-off effects upon our economy must surely be similarly wonderful. A win-win situation, we’re told. Handling people’s finances is good and more must be better still, right?

But is this really so? Yet again I had an idea and a question followed from that and, surprise surprise, the Guardian’s next Long Read addressed the same idea. This time they published first, but that is not going to cause me to bin my version of covering the same topic. Do read [1], their version, for their writers have far more practice and fundamental skill than I do.

So first of all what components of the resource curse might apply elsewhere? Let’s start with anything that pulls the economy in one direction and so makes others uncompetitive—‘crowding them out’ is a phrase I see often. So in the same way that North Sea gas would pull many people to Aberdeen, so money pulls people to London. Any dominant sector of the economy attracts people away from other sectors including [2] civil society and government, all of which harms our economy, our governance and our society. It is the ambition for personal individual success—which I’m going to call simple greed—that does us all harm. Of course, you may well say that at an individual level what you should be doing is exactly that, chasing the biggest possible pay packet. I say, and have said many times, that money is only one facet of your possible measures of success, and that perhaps the lesser target of enough money is more healthy.

So the argument that puts forward the idea that too much finance can be bad for a country, and Britain in particular, is based on the idea that the point-resource problem is being repeated. One of the issues with mineral wealth of some description is that the economy is subject to fluctuation in line with that of the significant mineral.

Such as copper in 2016 in Africa [3], Zambia particularly (DRCongo if you’re more up-to-date than me), which saw economic growth drop from 7% in ’14 to 3% in ’16. This might well be directly due to the Chinese economy historically growing in double digits and buying 40% of the world’s copper, dropping to more like 8% growth.

The persistent observation of resource rich countries with poor economies returns always to the concept to economic rent—receiving money without apparently working for it, simply selling the stuff in the ground. This is often blamed on corruption, but the previous essay explained corruption occurs when one has poor institutions. So does a large financial sector also encourage easy ‘rent’? [Answer; every time wealth is not created.] Off-shore banking is predicated upon levels of secrecy and the internal argument is that this money is going to go somewhere, so why don’t we have some of that? And once we’ve made that choice, why not have some more? We’re back to greed. See here, here and here (Japan) and here (Ukraine). Indeed it is greed that is the issue, though it is understandable at an individual level. What is called an ‘economic agent’ has interest in maximising throughput; this encourages all sorts of exploitation of personal contacts, hence informal institutions and immediately we pass into grey areas where transparency disappears and standards slip. When everything is rosy, the fact that some make more than others is less important than that everyone is making money; when the reverse applies what suffers most is trust in banking as an industry. I do not think we have yet seen the consequences of the 2008 crash in full yet, though I have read argument that the rise of populism is a direct consequence.

So if oil dependence causes rulers to be accountable to no-one but themselves, and aid dependence makes a nation accountable to donors (think of the control the World Bank exerts and imposes on recipient countries) and if taxation leaves rulers accountable in some way to taxpayers (who may also be the electorate?), then does financial dependence leave rulers accountable to finance? It would seem likely that this is so.

The test for rent-seeking is whether any wealth is created. The complaint is that the rent-seeker is wanting to move wealth in their direction, exerting self-interest. As Angus Deaton put it, “All that talent is devoted to stealing things, instead of making things.” [7] He goes on, intelligently, “The key is to somehow find a way of tackling rent-seeking, crony capitalism, and corruption legal and illegal and [to] build fairer, more equal society without compromising innovation or entrepreneurship,”

I notice an increasing frequency of people writing that appreciation of a monetary unit is not a good thing. Is that because I’m reading a different selection or because opinion is actually changing? I disagree with revaluation of the pound being a good thing much as I see depreciation as a mixed blessing. When depreciation occurs then locally it makes little difference, but exporting is easier and importing is more expensive. So that encourages us towards net exporting. Provided we aren’t trading in such a way that there is net material loss, I don’t see much wrong with this, though I do worry whenever we fail to be at least potentially independent for essentials like food and energy.

So is what is good for the City good for Britain? Is what is good for Wall Street good for the US? Do read [4] The Atlantic on this. Would you not expect that the 2008 crisis would result in more regulation? So why is there even less?

I am not saying that we do not need a financial sector. It is obvious that we need banking, insurance, pensions and the like. What is not so obvious at first is that there a point at which there is too much. That we reach a point-resource issue much as with localised mining. Source [9] argues persuasively that we have gone too far. The political question is then to understand and explain and act. What we need to understand is whether we were truly better off in terms of overall growth when our banking sector was smaller. I suppose we need to agree that economic growth is necessary assumption but I think that is already identified. We then need to persuade ourselves that we need to see the finance sector supporting other parts of the economy instead of mining, extracting wealth for itself.

Picking from [9] as matters leapt out at me and having read a lot of the report:

On assuming that there is an equivalent finance curse to that of the resource curse, one might attempt to calculate the cost of too much finance for the US and the UK. The authors think 2.5 to 3 years of GDP across 20 years from 1995 is about right. Applying the same thinking to the US gives about a year of GDP. That says, of course, that the effects of a finance curse is around three times worse for us than the US, which calls for more research (or explanation). Similarly one wonders where, if we have too much finance, the optimum size of the financial sector does lie. The published research identifies what it calls misallocated funds amounting to a huge sum, 150% of GDP, but that the effects are far greater, maybe 60% of total costs. I will explore what tis meant below. You could read the whole report for yourself at [9]

Misallocation of funds

How big is too big? When credit accorded (given?) to the private sector >90% of GDP perhaps. UK, 2016 134%, UK 2008-11 over 180%. Oh dear. Further reading puts the critical point between 90 and 100% (of credit to the private sector as a % of GDP). It is evident form the source I read on this (which of course might be a biased sample, but they are backing up their opinions with mountains of evidence and experience) that after some point such as the 90% mentioned above, having more credit and more banking produces lower growth, mostly because the finance sector is competing for resources rather than facilitating them. Graph to the right from here; the trend line is much quoted, but I say look at the scatter, which says to me that the trend line is unconvincing.

There are considered to be three factors to the excess cost imposed by an overly large financial system:

(i) The concept of excess profit (economic rent) measures —attempts to measure—that excess above what income an efficient economy would pay for the banking services which somehow is given a 15% range. This is a zero-sum cost, though it redistributes money to the financial elite (the primary direct beneficiaries of excess profits in the sector).

Source [9] says that the finance sector is typically paid 15% more than people with similar educational backgrounds in other sectors, but that this had changed from 20 to 40% in the period 2000-5, which implies, as [9] says that this 40% was rent, specifically excess compensation. That amounts to something like £3 billion per year1985-95 and £22 billion in 2005, 1.5% of GDP. What I find distressing is that the post-crisis figures still show excess compensation of around £8 billion per year. The graph looks like a mountain I might want to climb, but not by that route.

There is also an element of excess profit in this rent element. This is harder to model, but the suggestion is to set the lower bound at 25% and look at net present value. Profits ([9], still) from the financial sector were around £100 million per year before 2007 and around £65 million thereafter. The calculation produces an unbelievable £4.5 trillion as excess profit between 1995 and 2015, suggesting over 20% of 2015 GDP was this excess profit. And this, they considered, was a conservative model.

(ii) Misallocation (of funds) is the cost (is that price?) incurred by diverting resource into finance and therefore away from non-finance activity. Those costs include lost productivity, lost (lower) investment in skills and capital (that’s R&D hit hard). This is a negative sum because it shrinks the overall size of the economy. This is another negative sum cost, obviously. For instance, I read a separate article this weekend about expectations of employment as a new graduate, but learned that some 50% of (‘top') law jobs are reserved for graduates of other subjects, that there are 2500 graduates in sports journalism every year but that there are 64000 working journalists in Britain (a 25 year career would mean everyone in journalism has this particular degree) and that 25% of those in the biggest accounting firms didn’t do anything like accountancy at university. [Times, 20181006, Philip Aldrick]. Which means that not only are the universities ‘selling’ courses we don’t nationally need, but what you have isn’t what is bought at the other end. Yet we had 24,000 new engineering graduates in 2017 and need, I read, around twice that many every year. So if you study engineering, there will be course-relevant work. It also means that we need to cause there to be a link between what is needed and what is on offer. How we might do that is a political question; make engineering far cheaper to attend?

Among the processes that characterise financial over-dependence we have: Dutch disease; brain drain; rent extraction and attraction; financial volatility and crisis; uneven regional development; inequality and social segregation; political privilege and concentrations of power. The first three combine to produce a net crowding out effect in which other sectors are depleted of resources and are potentially at the nub of the misallocation costs suggested by the UK data. To provide balance we need to work against these trends directly.

(iii) Costs of crisis, particularly referring to 2008, but in a sense putting a cost on having allowed the sector preferential treatment. I’ve included Fig 1 from [9], which they explain fully (to encourage you to read it yourself). This is a surprisingly simple deduction as the graph to the right demonstrates, and though we might wonder about secondary effects, the graph pre-event is remarkably linear.

For Britain, while the excess profits are large they could be sorted quite easily politically. The misallocation costs are far larger proportionally for Britain than for the US, so deserve a deal more thought about how we might affect these in positive ways. That in turn possibly requires us to look at market incentives. What we need to see is money spent on R&D and technology rather than property and liquid financial instruments. As a prompt, look how little money goes into manufacturing investment (2%?). This begs to question the perceptions of risk in the financial institutions, which must be what governs their choices of where to invest. An opportunity for research (by you, not by me). How do high-productivity projects fail to garner finance? Something is wrong with the perception of risk, here. My reading points to what I think is a counter-intuitive fact, that manufacturing sectors that are either R&D-intensive or dependent on external finance suffer disproportionate reductions in productivity growth during financial booms. What happens in a boom moves investment toward property and similar assets instead of things that improve productivity. While I too can see advantage in moving money into capital, we have (recursively) a large industry encouraging us to move capital into financial ‘instruments and assets’ and the regulatory framework that encourages this. Changing this amounts to looking for a cultural change; not impossible but certainly difficult.

I wonder if, because of our very large and allegedly very successful financial sector, we have our currency significantly over-valued? I found references to ‘persistent overvaluation of sterling’ (go find a link). This works in a reverse way to emphasise our weak manufacturing sector, weak R&D due to chronic underfunding, poor productivity, poor pools of skilled labour (each an essay topic for you rather than me). In a sense, we are obviously badly prepared to have the financial sector shrink, but equally we clearly need it to occur – or at the very least for an awful lot more money to move out of that sector into others.

Similarly we need to reverse the brain drain that takes people who should be in R&D and plants them as financiers. Quite clearly the rewards built into the finance sector make this occur and reversing that position is long overdue. Quite how that can be done is not at all clear, but I’d expect to start by demanding far more transparency.

I find these arguments appealing. I am all too ready to believe that the City needs to be reduced and that this would bring a national-level benefit. I see few reasons for financial institutions to move because of tax reasons (show me some evidence where tax has made a difference, please) and I desperately want to see transparency in this sector, as I want to see reward for performance, not for existence. I find it entirely credible that we have too much money confined to a few, as I find it encouraging to have hinted that taxation is not necessarily the way that funds could be spread for nationwide benefit. I am left wondering if the dark cloud that is Brexit might have a silver lining after all.

The attraction of the ‘business as usual’ model requires post-Brexit Britain to shore up its finance sector exactly as the EU will be looking to do the opposite. Yet we have an opportunity to see the benefits of a reduction (and what I expect will include a seriously lower exchange rate). We need to see ways to make rent extraction far less attractive and in turn to find ways to encourage investment in more productive benefits. From the Norway model that would appear to mean investing in people, improving infrastructure and evening out the point-resource concentrations. That doesn’t mean we should not move loads of car manufacturing to Sunderland as much as it means we should balance such moves with other concentrations in other places.

None of this gets us away from the desperate need for some far braver political leadership. That suggests, sadly, that the cronyism of which the sector is accused applies just as much to parliament and government (they are not the same thing). We need transparency, and with that might come probity. If we could curtail the extremes of rabid behaviours of the press we might indeed manage to move from a position of collective desperation (cutting of one’s noses to spite, etc) to showing that leaving the EU allows us to sort ourselves out without going bust.

DJS20181008

Having finished this and published, on 20181021 there’s damning report from the IMF, reported at [10], added this morning. As I read it, this blames a very negative position on us being ‘overfinancialised’. Do read it, but at the same time wonder how much of this is bashing whoever, anyone but me. The fingers are pointed at neolberalism, whatever that is; I can see a concept as faulty or even wrong, but if blame is to be apportioned, an idea is not guilty, it is those that sold it and bought it who were wrong.

The Economist insists on me paying to read their content, so I don’t and won’t.

[2] https://www.taxjustice.net/topics/finance-sector/finance-curse/ the same author group as [1], with different links to similar content.

[4] https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/05/the-quiet-coup/307364/ argues that national politics is the obstacle to sensible economic change.

[5] https://www.soas.ac.uk/economics/research/workingpapers/file28855.pdf looks at banking in Japan

[6] https://scholar.princeton.edu/sites/default/files/Rent%20seeking_0.pdf specifically looks at rent-seeking and corruption in financial markets

[7] https://www.marketwatch.com/story/nobel-economist-takes-aim-at-rent-seeking-banking-and-healthcare-industries-2017-03-06 Also points the finger at the same occurring in healthcare.

[8] https://www.soas.ac.uk/cdpr/publications/dd/file48462.pdf A fund of readable content. I read about copper in Chile and Zambia.

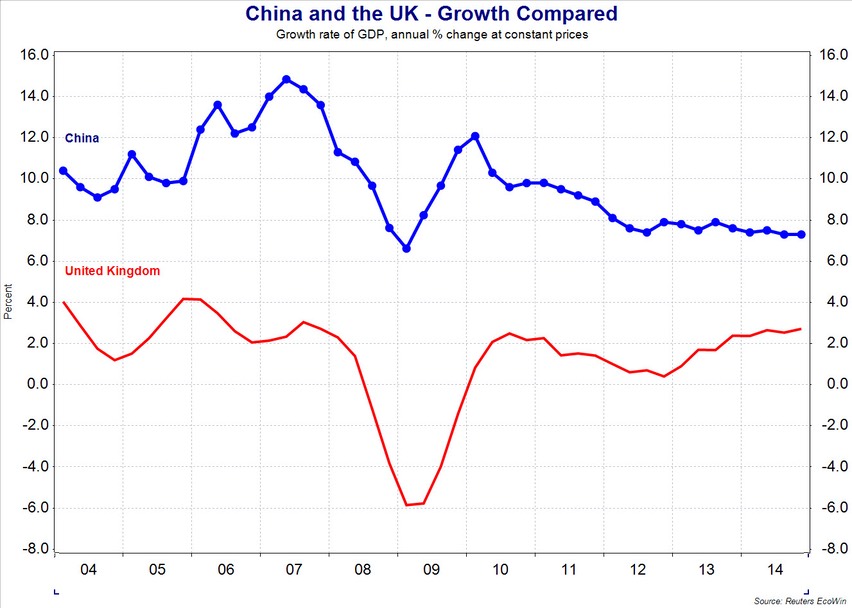

Economic growth: UK and China, US and EU compared. The left shows GDP per head in a limited selection of European countries along with the US and Japan (this is not the G7, which includes Canada; Russia was in the G8, China is not included even in the G12, though Spain is. The right hand graph shows growth rate of GDP for China with the UK for comparison. The spectacular dip is when the ban king crisis hit, affecting the UK far more than China because our banking sector is a far larger component of our economy.

Tullock paradox: Imagine someone sees that they would gain a billion from a particular political policy. The bribe to cause this to occur is hugely less, around 1% of the expected gain. The question is often framed as ‘Why is there so little money in politics?” wikipedia offers three explanations; (i) politicians are generally punished for taking large bribes and are relatively immune to consequences for hidden ones (ii) that environment causes any bidding to go downwards, not upwards and (iii) the lack of trust between parties and the inability to force compliance in either direction also pushes down the price. I wonder what form a ‘hidden bribe’ takes. Try reading this. Maybe a separate essay?