I want to write about work. I can’t tell a warts-and-all story until I have left teaching.

Those who know me best (and who therefore form the bulk of my readership) are still in Britain. Those there know the post of Director of Studies, the person who holds together the strands of the curriculum, steers things in sensible directions, encourages departments to expand without increasing spending, and so on. You know the post of Head, reporting to vaguely understood governing bodies, in charge of selling the school to customers (as an idea, not as the fabric), interviewing staff and students and holding the reins for everything. You know the post of Deputy Head, everything that gets pushed off the Head’s desk. You know the post of Bursar - everything to do with finance, building fabric, site development, catering, cleaning and support services.

The post of Centre Principal varies a little with Chinese employer. The academic version includes none of the Bursar’s role. It usually includes all of the Director of Studies’ work, all of the Deputy Head role and a good deal of the Head’s roles. Quite how much of these three roles is included depends on how distant Head Office is, in some sense.

There are various models for the ‘international’ section of a chinese school. I have explained elsewhere (oops, forgotten which essay covers this) that there are two types of international school in China. One takes exclusively non-Chinese passport holders – the incumbents are International. The other takes only Chinese passport holders and targets future education outside the national borders; for these, being international is the target condition. A very few schools are a mix of the two.

There are two basic models to house these schools. One builds a school site from scratch and sells a class act in terms of conditions and services; its fees are high to achieve this and so generally this model suits the foreign passport holder. The other solution is to find a host school, usually a very successful one, and somehow acquire space on campus and permission to function onsite. That might include the host school having a significant involvement, it might include a management fee for the organising company; it will probably run as a largely independent part of the larger school environment. Remember that schools (for Chinese) in China are huge by British standards: there are very few UK schools as large as 2500. The smallest schools I have worked at in China are that large. The smallest site I have worked on had 800 of the 4000 pupils on ‘our’ site, the largest had 2500 of 7000.

I confine my subsequent comments to the class of schools I have worked in, selling overseas education to local students. My experience is of selling A-levels—a gold standard of sorts—to locals who have a compulsion for overseas education. I have written about this before and have tried not to repeat too much content.

Interaction with the host school will vary with the financial commitment. One model I have worked within leaves the foreign staff paid directly by the host school but employed by a managing company who collect their own fees separately. Another leaves the complete organisation outside the remit of the host school, which does little more than collect rent and provide a few vague services. In both cases the greater part of the host school’s contribution is to lend its considerable reputation to the sale of places on the ‘international’ programme. Or program, if it is not A-level based.

There will be more...

DJS 20120225

Adding more ten months later, it is curious that the lady wife, Chinese, now works at the British version of an International school, while I work at the Chinese version. Adding emphasis, she reaches the end of a week wanting to eat European (food, not people) where I conversely want to eat western. Both of us are looking for contrast with the rest of the week. She teaches Chinese to little kids, using English as the other medium of instruction. I work entirely in English, though there is a growing need to be able to use Chinese.

In moving to an A-level programme, many Chinese forgo their access to a Chinese school graduation diploma. I don’t like the words, but the perceived need is for the little red book [see Graduation, within essay 31]. This is a folded card book smaller than A6 unfolded containing a little ink and a red stamp, constituting proof that the holder met the requirements of state education. Many folk cannot understand how Britain does not produce such a thing and those that follow the British system cannot understand what it is that this little red book achieves – or proves. They are probably available for purchase, though I don’t know how that is achieved. I am sure that overseas universities distrust these documents, questioning what they prove (or even evidence). The upshot is that every student is as good as the exams they took onsite, wherever they are.

One of the issues revolves around intake standard, which governs what products one can offer. The intake standard—at my current Centre, established by tests in English, maths and interview—is set so that we determine whether the applicant will cope with the speed of the course we are selling. There is an obvious friction between Sales and Teaching: Sales wants as many bodies as the building will hold while Teaching wants students they can teach at the speed advertised. The pyramidal nature of the market means that there are always many more people just below the decision point than just above it. I have quite convincing evidence that the people that didn’t meet the entry requirements are the same people who subsequently give us difficulties.

Of course, being China, there are other issues directly affecting even this simple problem. One, people want to buy hope; they also want everything immediately. These two demands mean that someone who needs two years to achieve GCSE (such as most of the UK) will be pushed by the family to join a one-year course, no matter how inappropriate that target or expectation. Indeed, families seem to prefer to fail and repeat, buying into the hope of success – even as they actually buy failure. Sales add to this because the customer doesn’t want to hear rational argument, it wants to be sold what it wants to buy, namely success. The face issue compounds this, in making sure people hear what they want to hear (what others think they want to hear). When I get parents sat in front of me they frequently say they give me loads of respect – and then ‘insist’ that they get what they want, which I would characterise as continued ‘progress’ in denial of the failure that caused them to be seeing me at all. You may have need to have that repeated: they say they give me respect and then proceed to ignore even the reason they have been invited to have a conversation. We do this in the west when people preface a refutation of an argument with “With respect...”. Liars.

This mess culminates, too often, in an A2 student (last year of school) still chasing a dream that is not actually theirs but that of their family. That dream can be described as ‘success’, but each step is only ever perceived as the next immediate target, typically the next ToEFL test. Or a SAT. This means that the whole of the teaching half of the last year at school is spent chasing a standard that should already have been reached. Some of the students are chasing impossibilities in a sort of determined-to-fail process; many of these demonstrate by their actions that they do not connect study with results, going off to the next repeated test fuelled largely by hope that this time the score will be better. Of course the planning issue (its lack) adds to the confusion.

So the observation is that hope will apparently bring success.

I can think of some religions that sell themselves in a similar way.

What can we do about it? Well, we try to inform parents and students where they’re at and what it means, but all advice is discarded as soon as someone else tells the desperate advice-seeking student what they want to hear. Critical thinking does not exist. That said, a few are listening and thinking. These are the people I want as customers, even if one consequence will be that they are much more immediately critical of our teaching.

DJS 20121225

There is more still to write, as I work out what I can say that is sufficiently general not to conflict with company policies. I gave up on the idea of writing more in 2017.

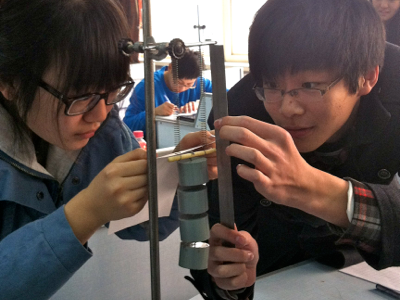

The photo is taken from some lab work (a practical).

The title refers to a US comedy series, The Office, which showcases extreme moments that occur in offices. School in China has its own extremes. There is quite enough material for a Chinese version of The Office, but I don’t know that they would see it as comedy.

Reading this again in 2017, I am struck by the memory of the efforts made to steer the students into taking English Language as a first language subject. The reason to do this is that the GCSE is a result with no sell-by date; it is a permanent achievement. An IELTS result is not the same at all bit must be repeated annually (or nearly so). The perception, written several times on this site, is that one MUST have an IELTS so as to apply for a visa. Not at all true; one must have an acceptable English qualification – and that means acceptable to the target country, not to the Chinese. So when we moved to Britain, one of the targets we set for the missus was to gain a GCSE in English – which she did, along with Maths and Biology, both being added for the primary purpose of expanding vocabulary, but the secondary purposes of interst and affirmation of standard. Yet, two and a bit years later, when she is assisted in class by a new import from China, when she explains that she (missus) no longer needs to take IELTS because of this GCSE C grade, the response is not merely incomprehension but fuelled by a belief that she has somehow cheated, that the GCSE must perforce be an inferior thing. Yet I must record that within her PGCE cohort, the majority grade for GCSE English was a C, at that her maths proved to be distinctly better than the norm, probably in the top three (including the science graduate). This tells us more about perceptions in China than it does about the effects of the British Council, who provide IELTS tests. As I grew steadily closer to pushing the whole year-group to move to permanent exam results so as to avoid IELTS altogether (and the frequent absence of students in consequence), so there was a revolt by the parents and the host school stepped in to prevent the change I was pushing for. About half of teh students actually understood that this was a loss, but fewer than 10% of the parents agreed. A little to my surprise, I rediscoverd that the loudest most persistent voice wins an argument but that reason does not. A precursor to the Brexit vote, then: why was I surprised?