I haven’t read any of the Harry Potter books. This is because I agree with Stewart Lee that, whatever the merits of JK Rowling’s work (and no doubt there are many), fundamentally the Harry Potter books are children’s books. I am not a child, nor do I have any children to read them to. The first book was published when I was already too old for it; I was at an age when, among other things, Alias Grace, Knowledge of Angels, Madame Bovary, Great Expectations, Rites of Passage, Lolita and Jane Eyre were more satisfying to me. I also read the whole of Wordsworth’s Prelude and the preface to Lyrical Ballads. I loathe Wordsworth from the depths of my soul, and yet I read the whole of the Prelude and the preface to Lyrical Ballads, and then I read Lyrical Ballads itself and all the other stuff we were required to read for A-level English Literature, because we were asked to.[1] As you’ll see in a moment, a troubling sense of misplaced obligation looms large in my reading choices the moment other people get involved in them.

Despite being too old for a children’s book (and seventeen is far, far too old to be reading a children’s book. If you’re experimenting with sex, recreational drugs and Christianity by day, reading about a pre-pubescent wizard by night is downright perverted), several of my coevals apparently forgot that we were all very nearly grown-ups about to be unleashed upon the world of higher education. I was badgered regularly by a friend who had read Harry Potter and the Prisoner’s Dilemma and thought I should do the same. No, I said. There are far too many grown-up books I’d rather read instead. He said, you don’t want to read it because it’s too long. No, I said. I’ve read War and Peace, Life and Fate and The Name of the Rose. I’ve read all the books in The Fortunes of War sequence and all of A Dance to the Music of Time.[2] I like big books, and I cannot lie. He said, I haven’t heard of any of those books. Oh dear, I said. I should shut up about books if I were you. Well, he said, as the point of the conversation thundered by him like a hungry Megalosaurus, if you like big books, you’ll like Harry Potter and the Pottery of Harr. No, I said. I’m too old for it. I will find it childish, which is not a fair criticism to make of a children’s book, but I will feel that way nonetheless because I’m not a child. He said, don’t be silly. You’ve already decided to hate it. No, I said. I’ve already decided that I’m a grown-up, and this book is not for grown-ups. He said, there’s nothing wrong with adults reading children’s books. No, I said. There’s everything wrong with adults reading children’s books, unless you are reading them to a child. It reduces your attention span. It removes your ability to respond to intellectual challenges, long sentences and complex ideas. Reading is one of the great pleasures of human existence, and you are trying to take that away from me by making me a read a book that cannot possibly satisfy me and was never intended to. If I had read it as a child and had happy memories that might be re-captured by re-reading it (as one might expect from re-reading 101 Dalmations, The Voyage of the Dawn-Treader, or, in a fit of irony, The Borrowers), fine, but I didn’t read it as a child and I don’t want to read it now.

He said, you’re a terrible snob. You don’t like it because it’s popular. You don’t read magazines because you think they’re sexist, and now you think you’re above reading anything popular. Fuck off, I said. First of all, I didn’t say I didn’t like it. I can’t dislike a book I haven’t read; I’m simply not going to read it. Secondly, I do read magazines (by which I meant Vagina Monthly, the only non-sexist magazine available in the late 1990s, which I had to buy from the cornershop in my head). Thirdly, I read popular stuff all the time. I read all the Sherlock Holmes stories last winter.[3] I read Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, which sold millions of copies. I read (and re-read) about 80% of the novels of (famously best-selling author) Dick Francis. I’ve read everything Terry Pratchett ever wrote, and he’s wildly popular.[4] He said, stop using books I haven’t heard of as examples. No, I said. I will use whatever examples I like in this conversation, which you initiated. You like this book because it’s literally the only book you’ve read for pleasure in your life. You’re not recommending Harry Potter and the Whatever of Meh to me because you enjoyed reading that book or because you think I’ll enjoy reading that book. You’re recommending it to me because it gave you an experience of reading that was actually fun, and that’s rare for you because you don’t read, and I’m happy for you that you finally had a good reading experience, but I don’t think it is specific to this book and I am not reading this book or any other just because you think I should. You don’t read. You know nothing about books. I do read and I know about books, and I can choose a book for myself without any help from you.

This dreary ding-dong went on for about four years, long after we had left school. Eventually, I hit upon a solution, which I recommend to anyone who finds their friends boorishly and dogmatically trying to make them read a book they have no interest in; it’s brutal, but they won’t ever force a book on you again. I said, fine. I will read your children’s book. You will lend it to me, and I will read it. In exchange, I will lend you a grown-up’s book of roughly equivalent length, and you will read that. He said, fine. Thus did two people who claimed to like each other conspire in and commit to a pointless exercise in a shared spirit of self-righteousness and spite.

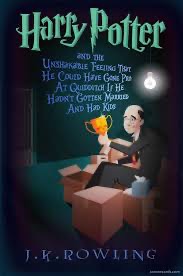

Let me be clear: I did absolutely did not want to read Harry Potter and the Demple of Toom, but I always read any book that has been loaned to me right to the end.[5] This is because, firstly, if someone lends me a book, I assume that they are doing so specifically because they think I will derive pleasure from the reading thereof. Secondly, I respect my friends’ ability to choose a book that is not drivel. Being given or loaned a book should be a rewarding, fruitful exercise, in which I discover writers new to me, carefully curated by thoughtful, well-read friends and relatives. For example, I recently read The Diary and Letters of Etty Hillesum, which was a gift from a friend. Not only did this book introduce me to Rilke, but every page was thoughtful, clever and sad, and I would not have read it otherwise. Thirdly and finally, if the book turns out to be drivel after all, it’s important to be able to enumerate clearly and precisely the many and various ways in which it was drivel, so that the friend in question understands just how wrong they are and never lends me any drivel again. This requires me to read right to the end, possibly taking notes. This is the only reason I have read all thousand-odd pages of The Executioner’s Song, one of the dreariest experiences of my life. I therefore prepared to read every last paragraph of Hairy Pooter and the Total Insect Fail and posted a book to my then friend. Perhaps this was the beginning of the end of our friendship (inseparable at school and in touch regularly throughout university and beyond, we no longer have anything to do with each other). A week went by and nothing arrived for me, so I emailed him. Where is that children’s book you were going to forcibly lend me? I said. He said, Ah. Well. Yes. The book you forced upon me arrived [notice how quickly he forgot the whole thing started with him forcing his book upon me], and I tried to read it.

The book I chose for my former friend was Bleak House. Dickens certainly has flaws (questionable attitudes to women; sentences longer than life itself; caricature as a default position; a total inability to let a moral lesson go unremarked, and so on), but let’s take a moment to recall the gloriously dank opening[6] of Bleak House. It is, famously, one of the great beginnings in literature (see Nothing but a Hound Dog for other spiffy opening lines), with its marvellous description of the suffocating fogs of the Thames: ‘Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits and meadows; fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers of shipping and the waterside pollutions of a great (and dirty) city.’ My favourite lines are these (only partly because they include a dinosaur):

As much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holburn Hill. Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snowflakes – gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun.

This splendid, sarcastic, swirling plug-hole of an opening[7] is also one of the reasons I chose Bleak House for my moronic former friend, reasoning that even if he felt he had to skip (say) some of Mrs. Jellyby’s twitterings later on, at least the first few pages would give him his second experience of Reading For Pleasure and he’d be into fun things like Plot and Character Development before he knew it. Yes, he would think to himself. A book. A big, fat, complicated book: suitable for a mature mind, demanding both concentration and engagement. A cast of thousands, full of ideas, intrigue, humour and mystery, plus a chap that spontaneously combusts and a load of funny names. A book indeed.

You tried to read it? I yelped at the screen, where his pitiful email crouched, embarrassed by its own existence. YOU’RE AN ADULT! I typed, pounding the keyboard much as a Megalosaurus might tenderise an intriguing meal by stomping it to death. You’re studying politics and philosophy! You’re reading lengthy, dry books full of complex ideas every day of the week! You tried to read it? Yes, he said. I tried. I managed ten pages before I lost the will to live. I didn’t know what was going on. I couldn’t concentrate on sentences that long. I couldn’t remember who anyone was. I’m sorry. I can’t read this. Don’t hate me.

Thus, gentle reader, Harry Potter and the Mansplainer’s Tome never arrived, so the moment passed and I never read it. I am not sorry at all.

——————————————————————————————————————July 26, 2018

[1] Based on the quality of the discussion that followed, the rest of the class didn’t feel the same sense of obligation. We never quite forgave each other for this mutual misunderstanding.

[2] I had even, God help me, waded through a considerable quantity of The Golden Bough, but I didn’t say so in case he asked me what it was about.

[3] I recommend this most highly, particularly if the winter is a pea-souper-ish one. One story per night, read last thing before bed in front of a roaring fire, with a hot, bitter cocoa to hand and a sleeping Hound on one’s lap, puts one in a splendid mood.

[4] He might have argued that, say, Truckers is clearly and explicitly aimed at younger readers (and no doubt he would have done, had he been familiar with the work of Terry Pratchett). He might have argued that all fantasy writing is for kids (it’s not, but no doubt he would have tried, had he known anything about the fantasy genre). He might have argued that the division between ‘children’s literature’ and ‘adult literature’ is a social construct, as meaningless to two people in their late teens as all the other divisions between ‘for kids’ and ‘not for kids’, but he didn’t make any of these points. Notice how his argument is limited at every turn by his total lack of reading and yet he continued to consider himself in a position to lecture me about books I should put in front of my face and into my brain for four entire years.

[5] I was a ravenous but less omnivorous reader at the time, confining myself almost exclusively to fiction, and I certainly hadn’t read or heard of Daniel Pennac’s Bill of Rights for readers. Had we known it, I was defending the first article (the right not to read), while my former friend was in some ways defending the last (the right to not defend your tastes). See both A ‘small mysterious corpus’ and Tom Sperlinger, Romeo and Juliet in Palestine: Teaching Under Occupation (Winchester: Zero Books, 2014), pp. 49-51 for a discussion of Pennac’s Bill.

[6] Fellow subscribers might also recognise this as a quotation from Vagina Monthly.

[7] See above. It was a bumper issue, with an unusually generous centrefold and an excellent crossword (down clues only).