I have wondered many times across the years just how many tenses there are available in English. Back at school I learned in Latin of the Present, Past and Future, but the past contained past perfect, pluperfect and imperfect , while the future included future perfect. Verbs have active and passive forms, though I am uncertain before researching whether every verb has both. There is a special form for the imperative, in Latin. So that suggests a 3x2x3 grid, in one dimension past present and future, in another passive and active and the last dimension three aspects (imperfect, simple, perfect) each state. So, if imperative, passive and active verb forms are just that, forms and not tenses, then we would seem to have at least 9 different tenses.

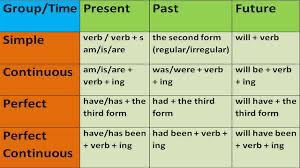

The table above demonstrates the case with English, an instant 3x4 grid and 12 verb cases. I rapidly found a suggestion that we can add 'future in the past' and jump to 16 tenses. Oh dear. I then found a suggestion that we have maybe 88, with this wonderfully complicated diagram as some sort of evidence.

Changes occurring

a. tendency to irregular morphology (learnt vs learned)

b. revival of the mandative subjunctive (We demand that she take part in the meeting

c. elimination of shall as a future marker in the 1st person

d. new auxiliary uses of certain verbs (get, want..) "the way you look you want to see a doctor soon"

e. Extension of the progressive, (the road would not be being built), to new constructions Similarly, has/had not been being built

f. increase in multi-word verbs. also called phrasal verbs, (have/take/give a ride)

g. frequency adverbs before auxuiliary verbs – emphasis perhaps intended (I never have said so)

h. do - in support for have; have you any? morphs to do you have any?

i. demise of the inflected form whom

j. increasing use of less over fewer with countable nouns. ((DJS regrets)

k. spread of the s-genetive to non-human nouns; the book's cover

l. omission of the definite article in certain conditions, (the) Nobel laureate Prof Smith

m. Singular they. Everyone came in their car

n. like, same as, immediately used as conjunctions

o. analytical comparatives preferred, politer over more polite

..and, from corpus-based research:

p. as far as as a preposition introducing a topic, perhaps replacing as for, as far as my situation, I am ....

q. Using following as a propeosition

r. like and be like as introducing a quote; I was like "...."

What is a tense? It is a way of framing the time of a message. We can clearly make a first pass at this by the time being now, before now or after now; hence we have present, past and future. We might easily grade the sense of when into near, medium or long into the past or future. Issues of whether we regard the future to be knowable (essay 59), 2010) are not relevant here. I found an argument that says English has only two tenses, present and past — that all reference to the future is done with modifiers. I found another argument that says tense is a way of counting the ways that a verb can be nuanced into indicating something different. This seems to me to be a pretty fundamental disagreement over the word tense. So we either have two tense, or three tenses or many, where that last larger number is using the general use of tense to indicate the many different ways a verb can be structured into a sentence. Since that is wonderfully vague, I think that 'many' is probably the only wise count. But we could perhaps indicate to ourselves the possible ways of referring to time and we might explore the shades of difference in meaning in the way the language is used. Well, you might and I might too, but not on here.

A period in time (say past time) could be flavoured by nearness, or actuality, continuation or not. Sci-fi ideas of time travel exemplify many hypothetical cases—example, if we were to change <this> historical event, then what we cal <now> could be entirely different, a conditional future that is somehow also the present, a hypothetical future related to a some past and, I suspect, quite distinct as a tense.

So it would appear that even the obviously helpful question "what is a tense?" leads straight to a minefield of disagreement.

Lets's look at these two extremes, two and many:

There are two tenses in English, present and past. This rapidly gets out of its own depth and, from what I read starts with the assumption that the bold statement is correct. To that is then added a collection of modifiers (see [2], answer 17); simple/continuous/perfect, active/passive; conditionals (certain, likely, unlikely, impossible); modals (Can, shall; could, should, would; may, might, ought to); and affirmative / negative / interrogative; some of our constructions recognise continuity, emphasising how long this action has been done. Nice complicated diagram here.

The argument that says there are exactly two tenses says that these other things are not tenses. That is defining tense as the grammar form of location in time. Then these other verb forms can be described as, for example, mood, aspect, voice or phase, each of which might then be subdivided. The argument is that there is a close match between the label and the phenomenon.

English has many tenses. This recognises that there are many structures, which is, I think, the root complaint. We can easily agree that there are many combinations of word that allow us to code for time (and intent and more) but there is no agreed fixed list. Example: The road has not been being built for several days is acceptable to some but not all as conveying meaning (precise or muddled, take your pick). [3,4] and inset text box,( e).

Inserted text box is largely from slides 6 to 8/16 from English Language development, the problem of a standard. [4].

Tense, Aspect and Mood - verb modifiers

Source [12] says verbs can be modified by Tense, Phase, Aspect, Voice and Mood.

Aspect [5] describes how a verb extends over time. The distinction between aspect and tense is not terribly clear mostly because we are imprecise in our use of precise terms, what is intended is that tense compares the speaking now with not now. Some languages have past and not past, some future and not future, some have all three (before, now and after), some have none (Chinese, for example). Some languages have more cases covered by tenses. That does not mean that complex time cannot be described, merely that there is not a distinct verb form to address this; In a <conditional state> I <possibly dissimilar conditional state > do action. No great problem: the distinction between tense and aspect is crucial to recognising this, but it is too easily left unclear in English.

Aspect breaks down into example categories (neutral, progressive, perfect, progressive perfect, and [in the past tense] habitual). As [5] puts it English aspects do not correspond very closely to the distinction of perfective vs. imperfective that is found in most languages with aspect. Furthermore, the separation of tense and aspect in English is not maintained rigidly. One instance of this is the alternation, in some forms of English, between sentences such as "Have you eaten?" and "Did you eat?" ... Rather than locating an event or state in time, the way tense does, aspect describes "the internal temporal constituency of a situation"... English aspectual distinctions in the past tense include "I went, I used to go, I was going, I had gone"; in the present tense "I lose, I am losing, I have lost, I have been losing, I am going to lose"; and with the future modal "I will see, I will be seeing, I will have seen, I am going to see". What distinguishes these aspects within each tense is not (necessarily) when the event occurs, but how the time in which it occurs is viewed: as complete, ongoing, consequential, planned, etc.

English uses auxiliary verbs to indicate aspect. Thus the present tense can have four forms; simple, progressive, perfect and progressive perfect. Here they are: I write, I am writing, I have written, I have been writing. Have indicates the perfect state and am/been the progressive. The distinction that makes I have read not the past tense is because the sense of tense is that it relates to the speaking now. Comparatively the same four aspects apply to the past tense I wrote, I was writing, I had written, I had been writing; Had for perfect, was/been for progressive.

In this construct, will indicates future and would indicates conditional, so we can combine these to form, for example, the future conditional perfect progressive, I would have been writing. As the inset list indicates, shall and should are disappearing

Mood is classed in five basic types: conditional, imperative, indicative, interrogative, and subjunctive. Mood, sometime referred to as mode (which I find a better word) describes the form of the verb; it describes the tone and hence the intention of the speaker or writer. [6] gives a breakdown of these. For the purposes of this piece it is sufficient to see that these moods are easily confused with tense; mood adds to the list of verb forms, but not to a count of tenses.

Voice applies to passive and active, but [11] indicates that there can be as many as 13 of these across many languages. In English the passive voice can be dynamic (get) or static (be) where I join the camp that says the dynamic get-passive form ios colloquial and (to me) it belongs in spoken English but not in writing. So for example this piece is read (by you) is static, while this piece gets read and this piece is being read are dynamic.

Phase is not easy to research because one is pushed away from connecting phase and verb to phrasal verbs. Phase refers in a way to the present / past distinction but is distinguished by point of reference. That is, a verb has either one or two points or reference: those with a single point of reference are called non-phased and those with two refer to a static or continuing state (point of reference) and thence to some other point before or afterward in time. I spent some time looking in the English Stack Exchange, heretofore a reliable source for authoritative opinion, but fell foul of the many mis-typings of phrase and came up empty. So [12] is really as far as I reached; I conclude then that this is an idea yet to reach university grammar courses, so either very new or very old or a topic of dispute. It may be that phase refers to a subset of the ideas included in aspect: I was doing something seems to me to refer to both now and the past, and so is a two-referent phase, while the passive form is non-phase, the work got done, as is the present active, I am typing.

I conclude that it is aspect that is the source confusion in attributing a number bigger than two or three to the count of tenses in English. The use of the auxiliary verb (would) in the conditional mood persuades that this must be a future condition and therefore, in terms of the description above, likely to be part of aspect — an aspect of aspect, indeed.

Can I persuade myself that English has only two tenses and not three? Here I turn to source [7], which is definite that Latin has a future tense but English does not. The distinction starts from agreeing that time and tense are not the same thing. In that case, what might the test be to establish how it is that the future tense does not exist?

Look at the use of will in these sentences:

I will try to explain. Will you be persuaded? Your patience will soon be exhausted; you will have to make up your own mind. You will change your mind only if I can persuade you. Some of you will have changed your mind by now.

Do you think that the use of will in this variety displays tense or aspect? I suggest that the test is that any counter-example, where using will fails to indicate futurity is sufficient to eliminate a future tense in English and establish that there is some other property indicated, to be recognised as aspect. The construction "will change your mind only if..." is perhaps timeless and ".. will have changed... is less clear still. We have willingness as an attribute, such that will not is compounded to won't so saying that teenagers won't listen to parents is a present state as much as it could be seen as a future state. Does that make will a word with several meanings, so that futurity is denied? Enter the construction to be going to, which in American English is too often gonna: this is slightly more definite than will as in the examples "They're going to marry" and "Will they marry?". For some, it is the construction of going to do something that is quite sufficient to satisfy; going to is definitely a present state of verb but it indicates a future action, so there is no future tense, because the compound word going to behaves as an auxiliary just as will does. The verb attached does not change, so English does not have a future tense. The sense of future is not denied, the verb has no change in the construction. Tense demands that the verb change, and it does not.

Last nail in the coffin; if will is a present tense auxiliary verb indicating tense, then it must have a past tense form. I say I can persuade you but I didn't say I could persuade you. I will try to persuade you; I wrote that I would try to persuade you. Can is used as both present and future (so it is deemed to be only present); in the same way will is seen as being present and would as past. Everything else is aspect.

I am, almost, persuaded. The fine distinction is not whether we can indicate small difference in intention or the sense of where in time an event may occur, but more that, having agreed that a past tense has many forms but that these are aspects of the past, then it follows that references to the future are, in English, constructed as aspects of the present. Therefore we have only two tenses in English, but we have many aspects of English and several moods, which makes for a large number of verb forms or structures (forms are not to be confused with tenses 1) available within the language with finely nuanced differences. It is not the tenses that make English difficult, but the subtleties of aspect.

DJS 20190303

top pic from google search 'tenses in english', first image offered. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=th8SNmRW69w

1 Having said there are many forms of verb I then find that Grammarly says there are exactly five. So I have a problem created by using form to indicate that many ways we can describe action and i must edit those occurrences. I changed form to structures

The five forms of verb are:

root, the infinitive without the suffix to so to see, to go, to be become see, go and be. Directly from this form we construct other forms:

third-person singular, he sees, he goes, he is, she watches, it shrinks, one does.

present participle, I'm coming, we're going, you're seeing. we will be showing, they have been eating

past (simple past) and past participle; regular verbs simply add -ed to the root, possibly with some doubling of a letter for pronunciation reasons, as in we watched, they shopped, you played, they had planned, those were stacked. Irregular verbs have different forms for the two classes of past, sing sang sung; see saw seen; fall fell fallen, give gave given; go went gone. There are many, see [10].

Using the order root, simple past and past participle, there are some verbs that cross the line between British and American English: dream dreamed/learnt dreamt, learn, learned/learnt learnt, similarly burnt, smelt, knelt, spilt, leant, spelt, spoilt. You might ask yourself if you comfortably identify these forms: proven, forbad, lain, slain, stridden. Verbs with but a single form include slit, wet (hence wet wet wet), broadcast, thrust, shut, set, rid, put, hurt, cost, cast, bust, bet.

Challenge: find more inclusions for each of these groups

Challenge: distinguish between BrE and AE,

Challenge: decide which you consider obsolete forms.

Verbs come in several forms: transitive and intransitive are well known. Spurce [13]

Transitive verbs have a direct object. The positive test is to see if the sentence can be inverted to the passive voice. You read this piece; this piece was read by you.

Intransitive verbs do not have a direct object. The screen glowed; the boy ran (faster than me); she spoke softly.

Auxiliary verbs you might decide these don't count, but they are verbs and they usually fail to form sentences (except by elision): I can, I will, I could all imply understanding of a following main verb. To be can also be a main verb, of course.

Ditransitive verbs precede two phrases and there are tow types. They are often clued by the verb give and to/for

.. indirect object noun phrase + direct object noun phrase, The readers gave the author a round of applause

.. noun phrase + prepositional phrase The readers gave a round of applause to the author.

Double transitive verbs e.g. perceive, consider, deem; verb + two phrases, the first is a direct object, the second an adjective, a noun phrase or an infinitive phrase. We consider this piece badly written. They deemed this piece to be the worst he had written. I am unclear and unceertain whether this is a verb class or a description of a sentence structure. See the challenges below.

Copular verbs (also linking verbs), e.g. be, seem, become, appear, look, remain. Copular verbs cannot be followed by an adverb (a reasonable test) but must be followed by a noun or adjective (which could each be word or phrase). The essay looked hurried; the source remained reliable. Neither the essay nor the source can be described as softly - they cannot be followed by an adverb.

Source [14] points out that verbs can also be classed as finite or not (non-finite, not infinite). it says non-finite verbs cannot be main verbs. There are mainly three types of non-finite verbs: infinitives, gerunds and participles. I think that any verb that cannot be a main verb is not a verb. These are infinitives, participles and gerunds, so these are forms of verb, not classifications of verb. I found the same confusion in the talk section of the wikipedia entries I read, not all listed below.

Verbs are often describe as 'doing-words' but there are many verbs that have no attached action (non-action words), such as those connected with the senses; look, smell, feel, taste. As in She looked good, the cheese smelt, it tasted bad. To these one can add verbs to do with existence (and desire, possession and opinion) such as prefer, like, possess, consider, own - I think some of these non-action verbs are copular verbs; apply the test above by trying to add an adverb.

Challenge: identify more copular verbs, but exclude those which can be used non-copulatively.

Challenge: Write three example sentences using different doubly transitive verbs beginning with the letter s. Are all transitive verbs also double transitive? Can you write a counter-example? Is double transitive a sentence structure and so not a class of verb?

Challenge: identify a ditransitive verb and a transitive verb (not typed in this challenge) that is not ditransitive.

Hunt, eat perhaps?

Challenge: There are some verbs, largely to do with financial transactions that accept three objects. Write three sentences with different verbs to demonstrate this.

I sold you a pup for free. I bought a kitten at no cost from the shelter. I hired a car from Hertz for less than I expected

[1] https://english.stackexchange.com/questions/91122/how-many-tenses-are-there-in-english

[2]] https://english.stackexchange.com/questions/91122/how-many-tenses-are-there-in-english

[3] https://www.academia.edu/24247691/Current_changes_in_English_syntax

[4] https://en.ppt-online.org/179803

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grammatical_aspect and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grammatical_tense

[6] https://grammar.yourdictionary.com/grammar/verbs/what-is-mood-in-grammar.html

[7] http://www.ecphorizer.com/EPS/site_page.php?issue=27&page=362

[8] https://www.lawlessenglish.com/learn-english/grammar/tense-aspect/

[9] https://www.grammarly.com/blog/verb-forms/

[10] https://www.englisch-hilfen.de/en/grammar/unreg_verben1.htm

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voice_(grammar)

[12] http://www.ugr.es/~ftsaez/morfo/vg.pdf

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Verb