There are, in principle, two types of domestic solar panel, photovoltaic and thermal. I have owned both. I attempt to discuss here whether they are cost effective. In so doing I have discovered that my own evidence does not measure up terribly well to the advertised advantages.

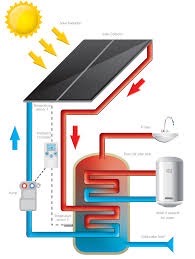

We fitted thermal solar panels (inset diagram) to a house outside Reading, UK. This amounted to two door-sized panels (flat plate collectors in the industry terminology) that worked very much like domestic radiator panels in reverse, covered with glass to make them more effective. Our supplier was “SunUser from Leeds” and we thoroughly enjoyed the experience. The package included increasing the tank storage in the roof space so we had two large domestic water tanks of the sort one usually refers to as having an immersion heater. The pipework circulated through the panels and through coils within these two tanks in a primary circuit at some pressure like 3 bar. The coils heated the tanked water as a sort of bank of hot water. Power was not collected, just hot water. An information panel told us the temperature of the incoming (tap) water supply and tank temperature (top and bottom, as I remember it, but perhaps top and bottom of the coils). Thus in the winter the incoming supply might be at 4ºC, the roof tank at 16-20º and so the domestic hot water system, target around 45º for a bath, was working around half as hard as it would with no system. We did not attempt to connect this to our domestic heating, only to supply hot water. In the summer, the incoming temperature would be around 16º and the tank could easily reach 90º at the top of the tank; when the bottom of the tank passed 60º we generally tried to find uses for hot water. Since the family was young we were using large quantities of hot water for washing selves and clothes and we were under the impression that our heating costs had reduced by so much that the system had paid for itself within five to seven years. If we had also used the warm water in the winter as a source for the heating system—though I imagine that would require some extensive rethink of how domestic plumbing works—we might have had a far faster return.

I observe that our power bills amount to 15-25 MWh per year (1MWh is 1000 kWh, the unit that bills are expressed in) of which I can identify 2/3 as being for heating. This can be reduced dramatically by (i) raising the EPC rating of your house (the house in which I write has an EPC ¹ in the low 80s), where previous houses were probably down around 50 and the average for England and Wales is 60). The EPC figures suggest that the typical national use amounts to 16.5MWh/year (for a house rated like ours), water heating 2.4MWh/y. The same document says the gain from 2.5 kW rated PV solar panels will be £790 per year and it recommends this as the top action to take. See nearby essays, but particularly 223 and 221.

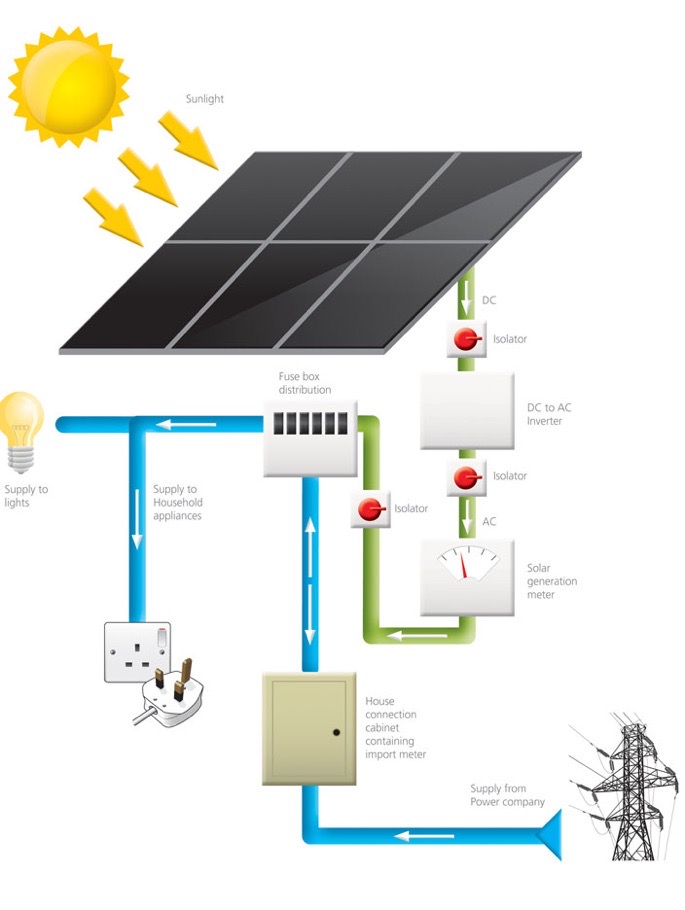

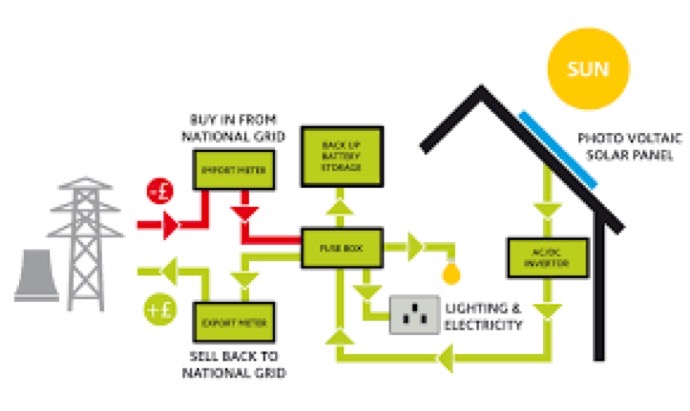

So, after due consideration and based on the assumption that we would be in the house many years, we did install solar panels of this second type. These photovoltaic models generate direct current electricity that is then rectified (a box the size of a suitcase sited in the roof space) and added to your electricity supply. This means that you will be using your own generated power and the difference, positive or negative, goes into the national grid. You pay for the panels, in our case £8000 for not quite 3kW capacity. You collect income for generation and for export. The government guarantees that you will be paid at this rate for 20 years. So those who jumped on this a long time ago are still being paid 40p per unit, while we are on about 15p per unit and new purchasers on about 5p per unit. Mind, the cost of the panels has dropped too, so the point at which the system has paid for itself have been similar, at around seven years. They say; I reckon ours will be more like 12 years.

The combination of pay types is strange, considering how clever metering can be: one is paid (this is England, it may be different elsewhere in the UK) for generation, at around 12.5 p per unit (it varies according to rules I cannot find); one is paid for export at 4.91p per unit, BUT there is a ‘deemed usage rate’ of 50%. So in effect we receive all of the first rate and half of the second, very close to 15p per unit. Across the last year we have generated 2300 units and so will eventually have been paid £345 for this. But we also have not paid for these same units, and if we actually fitted the deemed usage rate we have not bought 50% of 2300 units at 13p, another £300. So our saving is expected to be £645. In practice, one can do a lot about this, especially with me living in the house most of the time; run all sorts of things, but especially the (electric) oven and the washing machine, in the sunlight, when the power is in a sense not only free but earning. Basically, one tries to exceed the deemed usage rate. I doubt that I succeed. I achieved quite a lot by buying a watt-meter and discovering the power usage of lots of kit around the house, particularly when on ‘standby’. This informed me as to what I really should turn off when not in use; my desktop computer was the biggest culprit, though turning it off has made the office really quite cold. We already have all our lights of the low-wattage variety (the EPC says that’s around £400 not spent, £200 a year in actual cost now). The house is heavily insulated relative to 1980 thinking, though I expect that will be upgraded again in the years to come. 50mm roof insulation is now 250mm, for example. So clearly the panels aren’t generating these savings directly; there is an attached awareness of energy spend that causes a significant change in domestic behaviour.

Those homeowners on limited incomes in the UK can access the ‘green deal’, which has a remarkably low uptake. The idea is that the capital is spent on the property and the costs are loaded (spread) onto electricity bills, so that the pain of the capital is spread among the gains from reduced consumption. ² I suppose that the spend still puts people off; money now being far too precious. In theory, this is not increased spend, but the same money that would have gone on the bigger bills instead goes to pay for the capital work. The more I think about this, the more I wonder why one would take it up; there is no gain until the loan is paid off through the electricity bills; you’d have to be in the house a very long time to recover any benefit. No wonder then that councils have been fitting the kit and that relatively rich businesses are buying up roof area for generation.

Speaking just on figures I can prove (our own), power consumption has fallen from £100 per month to £40, consistent with £700 per year. I’m not prepared to go to a second significant digit because I think that weather variability and usage changes account for too much to declare greater precision.

But then we come to a second matter, that of increased value to the house. Or not. The feed-in tariff, or FIT, is a guaranteed payment for the twenty years following the granting of the certificate. So this is worth some £14,000 of money not spent, at current prices. The house owner not only collects these benefits, but has the cheaper electricity for as long as the panels last, quite possibly a good deal longer than 20 years. The panels in our case cost £8000 to install (and make work, since the installation was not done entirely correctly).

Therefore one might expect, as we did, that the house value would reflect this advantage. The agent valuing our house disagreed, adding a value of zero.

Yes, zero.

So I valued the house at £10,000 more than we bought it for on the panels alone, I went for such an increase irrespective of the other improvements, which I valued at up to £5,000. A difference of £15k with our neighbours will not be tolerated by the market as such things are explained to me, but £10k may be tolerated. Yet the very first person shown around the house went rapidly from £k115 to £k125 and the agent is already crying ‘Stop’. From which I conclude several things: (i) the valuer is in need of education, and (ii) in turn estate agency in general has lessons to learn. ³

In response to the valuation attributing no gain to the capital added to the roof, I went in search of information, which I then put in an email to the valuer so that she would be better informed (and so, I hoped, she would revise her opinion). What happened was a cycle in which the number went up but only because I was saying what I would sell for, not what the agency opinion thought the market would accept. ⁴ This, again, is not what I think agency is. ³

What I found in research was two contradicting arguments. Summarising these, I found a set of opinions that said that the market saw no benefit (or at best that it was too early to tell) (example); inevitably I found some more blatant fence-sitting (example) and eventually I found someone supporting my own view, that it ought to affect the value (example).

If you read the examples you can see that the possible value depends on how the panels were bought – which amounts to who owns them and their output. Hence, who owns their benefit. A sensible next question is who did the work (i.e. was it a registered installer, not are they still in business, because the issue is whether the work was done to the recognised standards) and then to establish when the installation occurred, as that greatly affects the FIT and the length of such returns.

Actually, I can make a case for installing PV panels in 2017 with the vastly reduced tariff. I can, I think, justify their installation on zero tariff, but only if I can guarantee that it is myself that has the gain, since I cannot satisfy myself as yet that the rest of the population sees any gain. Which (to me) is patently ridiculous, but equally clearly I am in a minority. That may have far more to do with the use of capital to reduce consumptive spending than anything else. I do not see any way in which energy will become cheaper in the future, nor do I see energy rising in cost at a rate slower than other expenditures (once we’ve gone past the consequences of Brexit). Therefore I see the savings as free electricity while the panels are generating, plus some token payment for the export into the grid. As battery provision improves, so the opportunity to top up one's own domestic battery from the solar surfeit / surplus (before exporting the residue to the grid) strikes me as a future benefit. Since the panels have no moving parts, they can be expected to last a very long time and there are many factors that should drive the cost of panels downwards.

What I expect to see is the panel replacing roof surface – at the moment it is additional, and from my desk I can see the gap underneath the panels of a neighbour. That should be reflected in building savings (less roof covering, different and improved construction). As the panels become steadily cheaper there may well be incentive to cover far more surfaces with them, where in Britain at the moment we are fixated on surfaces close to perpendicular to the sun’s rays, we might well look to cover many horizontal and vertical external faces. We may even move towards using DC more, cutting out the loss from rectification. ⁵

Looking further ahead, it seems to me entirely sensible to be looking to reduce the energy consumption of myself and my housing. The cost of energy, particularly heating, amounts to a large part of my annual costs. As a retired person I am actually quite well off for capital but poor in income. That means that I am far happier spending capital in ways where I convert money into other value. Buying a car does not do that, as depreciation heads toward zero. Putting money into one’s residence gives a similar return to that of car but also generally appreciates. One can argue that spending on a house is greater than the gain, but I think we can successfully argue that such apparent loss is less than for transport. I may well attempt to produce figures for this.

DJS 20170222

most of this written two weeks earlier.

top pic; installation at Purley Close, Wallsend. Our house at the time.

If the opportunity is ever presented, I will ask the buyer of our property for their thinking regarding the panels. Obviously this is a case study, not general research; one person’s opinion does not necessarily reflect an attitude across a whole society.

I shall extend this essay after I have installed PV solar on the latest house. I am hoping to have 4kW this time, but I do not expect to have a FIT.

Just mild annoyance.

After another year of output I will be able to add figures for whatever return there is. Quite clearly I am not going to find any unbiased information – info that I can satisfy myself IS actually unbiased. You might even say the same about my own writing. I’m a fan of being greener and I’m prepared to put some money up to find out.But at the same time I would like to think I’m being honest over what it has cost and what it is returning. Discovery will begin in 2019.

1 Energy Performance Certificate, now a required document for a house in this country. I use ours to provide info on this page where I want typical national figures, not our own domestic.

2 That’s what the Green Deal is supposed to address – it allows for capital expenditure and significant gains with virtually no direct costs, hidden by the energy savings. Yet the national take-up is minute. Something for politicians to address in detail.

3 On a larger scale I am hugely disappointed with estate agency as a business. No agent we have spoken to in the last three years has offered any opinions and indeed they have gone out of their way to avoid expressing any opinions. This has the effect of reducing such people to know-nothings; they will happily go seek out what is public information but they simply refuse to turn information into opinion. If this is the result of legal persecution, we are all the losers (and I deplore the system that has allowed this to occur). I had no trouble finding a specialist surveyor happy to tell me what was potentially wrong with a house, but he was not portraying himself as any sort of estate agent. We have had a very similar experience with solicitors acting for conveyancing. Fortunately, I have no problem with accepting that we must make decisions for ourselves; my complaint is that the people we are paying for advice will not give it. Worse, when I dragged the estate agent into giving advice, it was quite clear to me that what they were doing was not expressing an opinion in my interests, but in their own. That is not what agency is. Or not what it was, at the least.

4 Yes, there is a mixture of first person singular and plural. This is our house, but it is (has been) my task to sell it, a matter on which we were already agreed.

5 Not an irrelevance; when trying to work out what was wrong with the set-up on our system, I found out that the rectifier uses up to 400W of the not quite 3kW capacity. So, as I understand the numbers, that means that at maximum solar gain we consume 400W of that in converting from DC to AC. That is an in-built loss at design level of 14% (2s.f correct), arguably an unnecessary one. How the consumption varies at lower solar gain, I do not know but presume the power costs to be similar.

The current house has a south-facing roof, but we are denied the right to place PV panels on it, because we live in a conservation area. I disagree with the decision, but hard luck. I can find NO information telling me about PV energy production when the panels are not placed optimally. In theory, the PV type needs ambient light, while the thermal type demands direct light. This could be an expensive experiment. Clearly the recovery time will be extended, but there will be some gain, however reduced. In effect I will need a lot more panels for the same energy capture. That essay cannot be written until late 2019.