My brother, in responding to essay 258, pointed me at the 2009 book, The Spirit Level, which argues that inequality within societies weakens them and that greater equality makes them stronger. The evidence to support such claims is disputed and the strongest claim against the underlying claims is that the basis for the conclusions is made on statistics that demonstrate selection bias.

One must applaud the efforts made in this book to identify a trend that many of us would like to see proven. In that sense alone the book must be judged a success. To have shown that less inequality would make us all better off is exactly what politicians would like to be true, and if we could turn that into a widely understood concept, proven not just wished, then we would already be all better off. The criticisms of the stats, which would have been backed up rigorously in an academic paper—and were indeed better supported in later editions—are justified from that standpoint and at the same time not justified criticisms of a paperback publication. Arguments based on failure to replicate results reduced rapidly to academics pointing fingers at failures to understand how to do statistics and what sources would work reliably in making comparisons. Which looks, I have to say, far too much like academic spats everywhere, when what those of us outside academia want to see is rapid agreement on a truth, not a spreading argument that reduces one’s faith in the academic industry and its ability to deliver answers. Which in turn is more worrying, since that is mostly why they are funded, to give answers. Of course, the issue is itself encapsulated there: do we want answers, or do we want the answers we want to hear, or do we want answers that are shown to be based on correct data, analysis and conclusions? In some sense the argument is healthy but only if all the parties are agreed that the objective is truth rather that fame or reputation (and the rewards that those bring).

The strongest criticism of the work in the Spirit Level comes from Chris Snowdon, who published the Spirit Level Delusion in 2010. He points to many suspect decisions, confusion between correlation and causation (there’s a trap easily fallen into), selective choice of datasets and the strong effect of outliers on significant conclusions. The original authors, Wilkinson and Pickett, made response and Snowdon made reply. Do see [1] for sources, rather than me list much of the same, since the wikipedia list is far longer than the material I read or dipped into. I quote [1]] what might be considered a ‘big gun’:

In 2011 the Joseph Rowntree Foundation commissioned an independent review of the evidence about the impact of inequality, paying particular attention to the evidence and arguments put forward in The Spirit Level. It concluded that the literature shows general agreement about a correlation between income inequality and health/social problems, though suggested there is less agreement about whether income inequality causes health and social problems independently of other factors. It argued for further research on income inequality and discussion of the policy implications.[34]

So, did this public spat produce a conclusion? The quote seems to tell us that there is a correlation between income inequality and health/social problems. It also points out that there might be other (significant?) factors causing those problems. What we need to see is some evidence that removing the inequality removes the social problems, as we need to see whether removing the social problems can be done without changing the income inequality.

Richard Wilkinson was subsequently appointed to a position to study inequality in Islington, one of 32 London boroughs. Islington [2] is a small borough with a third (34%)of its population in poverty; child poverty is among the highest, but the rate of low pay is low (14%) and unemployment is close to the average for London. Income inequality is high. See [2] for detail, which gives rankings of the boroughs on a wide range of measures. That doesn’t tell us anything about what does or does not work. It gets us no closer to understanding what effective actions could be taken to affect income inequality, or the behaviour consequence of that, or the other factors not identified. I found no published information from Islington taht said the ideas were being put into practice and having any of the desired effects. I’m not at all saying there si no change, I’m saying I couldn’t find evidence of change, particularly some detail at the level of “We changed <this> and <this benefit> occurred”.

If we assume for the nonce that income inequality is a bad thing, then there are several policy suggestions that would change this position. From [3], the Haas Institute, I have:

(i) increase the minimum wage, which should move people out of poverty, you would think. In theory this hurts neither employment not growth.

(ii) implement tax reform. In the US this is labelled as ‘expand Earned Income Tax'. I think the equivalent action in Britain would be to raise the tax thresholds. This is coupled, in the US, with a change to making tax more progressive (which I think translates as removing privileges for the rich).

(iii) Build assets for working families. This means cheaper or affordable housing, higher savings rates, retirement plans - things that build wealth. I’m struggling to translate this from the American position. I couple with this a need to end segregation, which occurs far more in the US than the UK (which does not say it doesn’t happen, just to a lesser degree).

(iv) invest in education. This, I suspect would have the biggest impact in terms of long-term change to inequality, leading to economic mobility and increased productivity. What does that mean in Britain, a return to free university or equivalents?

Trying to tie this down to a British set of actions, I found [4], the Rowntree Foundation again. Tim Harford’s list but my spin on each.

(i) identify the underlying causes. What causes income inequality to occur? What of that is bad, and for whom? In a sense, this draws us to fundamental like how we would like our society to be. “Not like this’ is not good enough.

(ii) smarter redistribution, which usually means taxation and benefits, but in Britain probably means a less complicated and transparent structure, particularly with regard to the elite.

(iii) fix the apparently trivial stuff. As Tim Harford points out, when your social structures aren’t working it is no wonder the results include such inequality. Education child care (repeat, preferably subsidised), public transport, security (safety, perception of that, policing), council services: all of these need to occur as effectively as elsewhere, possibly subsidised from central government, and for each of these to be seen as a good thing, appreciated, desirable and valued.

The ‘publish and be damned' moment appeared. Went to the gym. Possibly more to input here, but I’ve temporarily lost interest.

DJS 20181011

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Spirit_Level_(book)

[2] https://www.trustforlondon.org.uk/data/boroughs/islington-poverty-and-inequality-indicators/

[3] https://haasinstitute.berkeley.edu/six-policies-reduce-economic-inequality but do google this and read for yourself.

[4] https://www.jrf.org.uk/blog/three-ways-reduce-inequality-britain

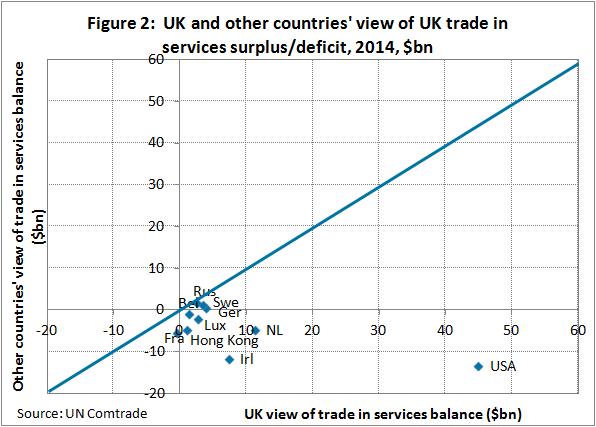

Continuing to consider this general problem, I found, 20181023, a different example of discrepancy. According to the UK we have a surplus in services with several countries, but each of those reports the opposite, that they have a surplus with us. Most extreme of these is with the US, with the USA reporting a trade in services surplus with the UK of $13.3 billion compared with our UK data reporting us to have a surplus with the USA of $44.8 billion. [5] and fig 2 [5] to the right. These discrepancies are called trade asymmetries and are both common with and similar to those of our trading partners; it is to do with what we record, how and when. See {5] §7. I may have found the biggest discrepancy in trade (quite accidentally) - a disagreement of some $58 billion. An alternative report is here, from the FT. Longer ONS report. This source [6] does at the very least demonstrate how much work goes into trying to reconcile these figures. One of the problems is that the Crown Dependencies (think banking on the Isle of Man and in the Channel Islands) are excluded at the British end and included at the American end, so the quite significant money business shows up in the US figures. Similarly, the inclusion of financial intermediation services indirectly measured (FISIM) and net spread earnings (NSE) in financial services by the UK, but not by the US. if you want to study this, start here, though I think much of this is also in [5].