With so-called 20/20 hindsight that is to my mind still proven myopic, we can look back at the 2008 crisis and attempt to explain and understand it.

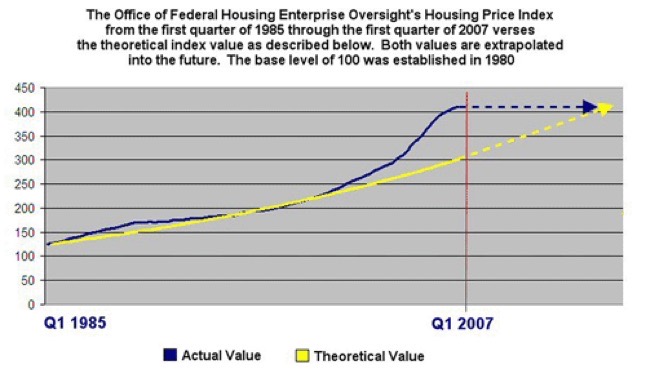

At root there was a housing bubble in the US funded at least initially by bankers refusing to recognise their assumption of accelerating growth. Every case of accelerating growth will result in collapse, as the model is doomed to fail. It is (to me, obvious) necessary to have balances, usually brought about by integrity and honesty and, where that cannot be assumed, by law and regulation.

When stocks rise disproportionately this increases wealth and permits spending based upon borrowing against that wealth. This led to the consumption boom of the late 90s, with the savings rate out of disposable income falling from close to 5.0 percent in the middle of the decade to just over 2 percent by 2000. [source].

When the bubble burst, a story in itself, this forced banks to write down several hundred billion dollars in bad loans caused by mortgage delinquencies. At the same time, the stock market capitalisation of the major banks declined by more than twice as much. While the overall mortgage losses are large on an absolute scale, they are still relatively modest compared to the $8 trillion of US stock market wealth lost between October 2007, when the stock market reached an all-time high, and October 2008. This paper attempts to explain the economic mechanisms that caused losses in the mortgage market to amplify into such large dislocations and turmoil in the financial markets, and describes common economic threads that explain the plethora of market declines, liquidity dry-ups, defaults and bailouts that occurred after the crisis broke in summer 2007.

The same source explains the banking side like this: To understand these threads, it is useful to recall some key factors leading up to the housing bubble. The US economy was experiencing a low interest-rate environment, both because of large capital inflows from abroad, especially from Asian countries, and because the Federal Reserve had adopted a lax interest rate policy. Asian countries bought US securities both to peg the exchange rates on an export-friendly level and to hedge against a depreciation of their own currency against the dollar, a lesson learned from South-East Asia crisis in the late 1990s. The Federal Reserve Bank feared a deflationary period after the bursting of the Internet bubble and thus did not counteract the buildup of the housing bubble. At the same time, the banking system underwent an important transformation. The traditional banking model, in which the issuing banks hold loans until they are repaid, was replaced by the 'originate and distribute’ banking model, in which loans are pooled, tranched and then resold via securitisation. The creation of new securities facilitated the large capital inflows from abroad. The first part of the paper describes this trend towards the ―originate and distribute‖ model and how it ultimately led to a decline in lending standards. Financial innovation that had supposedly made the banking system more stable by transferring risk to those most able to bear it led to an unprecedented credit expansion that helped feed the boom in housing prices.

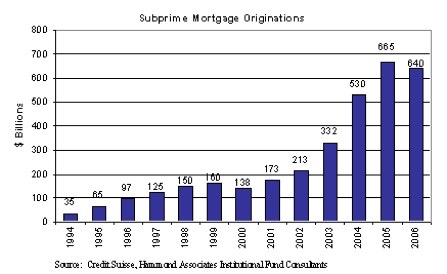

A different source describes the same history a little differently; The housing market experienced modest but steady growth from the period of 1995 to 1999. When the stock market crashed in 2000, there was a shift in dollars going away from the stock market into housing. To further fuel the housing bubble there was plenty of cheap money available for new loans in the wake of the economic recession. The federal reserve and banks praised the housing market for helping to create wealth and provide a secured asset that people could borrow money to help the economy grow. There was a lot of financial innovation at the time which included all sorts of new lending types such as interest adjustable loans, interest only loans and zero down loans. As people saw housing prices going up, they were stepping over each other to buy to get in on the action. Some were flipping homes in an effort to take advantage of market conditions. If you understand fractional banking, you would know that with a 10% reserve requirement, in theory it would means that 10 times that money can be created for each dollar. With 0% down needed to buy new homes, an unlimited supply of money could be created. With each loan, banks would quickly securitise the loan and pass the risk off to someone else. Ratings agencies put AAA ratings on these loans that made them highly desirable to foreign investors and pension funds. The total amount of derivatives held by the financial institutions exploded and the total % cash reserves grew smaller and smaller. In large areas of CA and FL there were multiple years of prices going up 20% per year. Some markets like Las Vegas saw the housing market climb up 40% in just one year. In California, over ½ of the new loans were interest only or negative-amortisation. From 2003 to 2007 the amount of subprime loans had increased a whooping 292% from 332 billion to 1.3 trillion.

One of the criticisms of the businesses and banks concerned is that the level of leverage was not the ten implied in the description of fractional banking, but figures of 30 or 40, which follow from using the magnified sums as if they are already wealth.

The housing bubble burst as soon as some of the sub-prime loans went into default.

This needs quite a deal of explanation. A sub-prime loan is one made to a person or persons who are likely to have difficulty meeting the repayments; their situation is less than comfortable, so usually the interest rates are higher in reflection of the increased risk of default. The prime rate is that set by the Federal Reserve, what we’d call bank rate in Britain.

To default on a loan in the USA usually means no payment has been made in a set number of days. For a longer explanation, see here.

The sort of people who resort to a sub-prime mortgage are those with a poor credit rating and history, so they have a need for short-term loans of two or three years, during which time the investor is keen to move the loan into a prime mortgage (one that is much more affordable). The whole scheme (scam, virtually) relied heavily on the assumption that houses would go up in value (graph showing this) and the mortgages were ‘sold’ on the basis of the new improved value at the end of the sub-prime loan. In effect, people were being encouraged to borrow on the strength of assumed future increase. This is the essence of all pyramid schemes and surely anyone with any brains in use [or with an eye looking outside the trough of greed] knew this was doomed to fail. The US government has a number of state-sponsored mortgages (VA, FHA, etc) that avoid the punishing rates of sub-prime borrowing.

Normally, default levels are low enough for the outstanding missing money to be covered by the other payments — this is why the interest rates are high. So those rates are set on the basis of assumptions of default levels. But in this case the market was itself changed by the volume of traffic and by the national conditions which were pushing housing as a good thing to invest in, so no-one was looking too hard at the failure of assumption (and I’m sure that anyone who said something cautionary was roundly told to shut the hell up and get back to selling, called ‘making money’).

So it would not take all that many people failing to meet the expected payments to cause a problem. What is still not clear is the detail of that.

The sort of loans made were interest-only, short-term, with low introductory rates (that would rapidly rise) and often no down-payment at all. The hope was that the house price would appreciate by the time the loan fell due and that this increase value would allow that equity to be used to not only pay off the loan but itself finance more borrowing and spending. [Is that not how a pyramid scheme functions?]

The blue diagram nearby is from the investopedia site, showing an estimate of subprime mortgage originations (sales) from 1994 to 2006. In 2007 the loans made in 2004 and 2005 would have fallen due for capital repayment.

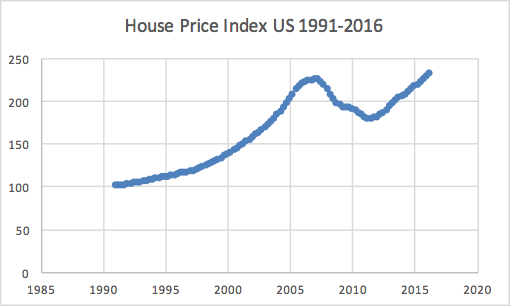

Of course it is not just the lenders at fault and the press has tended to describe the borrowers as uninformed, uneducated dupes. So when the house market failed to meet expectations, as shown below, the expected equity was not there, so the refinancing could not occur, so foreclosure was for many institutions, an automatic response.

This House Price Index diagram, if it works, has been produced by me from the data available here. I used the purchase-only index figures with seasonal adjustment to smooth it. 1991 is set as 100, about 175 on the earlier y-axis.

The bubble bursts when excessive risk-taking becomes pervasive throughout the housing system. This happens while the supply of housing is still increasing. In other words, demand decreases while supply increases, resulting in a fall in prices. Read more Factors that would do that include (i) an increase in interest rates (ii) a downturn in general economic activity (iii) exhausting demand.

Speculators were relying upon the rapid change in house price appreciation. This is a nice term encompassing both the perception of change, the perception of the future price and, somehow the promise of that upward spiral. A false hope.

The short version is that far, far too many people were being greedy. The disaster is that this greed led to the general investor and house-owner suffering while the bankers, in the main, stayed (un)comfortably rich. The wider disaster was that the greed in one country affected far more than those who were being greedy and far further away that their shores.

Some of that same greed spread and the Meltdown video makes much of Iceland’s situation. The greed spread across world banking and it is notable that the banks which were less affected were those with more sensible attitudes to risk, or perhaps those in which risk was assessed and balanced. Big money is made from big risks and history records and rewards the successful risk-taker. The evidence, though is that history shares out the misery far better than any share of success.

Leverage A leverage rate for a foreign exchange investor who has a ‘margin deposit’ of $5000 and a leverage ratio of 50, can instigate a trading position of up to $250,000. Leverage rates in such institutions range between 50 and 400. Leverage rate is, properly, the values of asset / equity.

Imagine you own a house whose market value is 300k and on which you have a mortgage of 100k. Your equity is 200k, your asset 300k, so your leverage is 1.5. But for my first house I put down 20% and borrowed 80% on the basis of joint income—the promise of money—and it is no longer clear what the leverage really is; asset/equity was 4. when house prices dropped in the late 70s and interest rates were over 20%, many people went into negative equity (they owed more than the house was worth at that moment), simply because they had borrowed too much. Banks might be leveraged at 30 (when 10 would be more sensible); insurance companies might be leveraged far higher [10 units of cash, 200 units of insurance cover, this 20x leverage and if customers make claims to 5% of value, they’re out of business overnight].

The third quarter of Meltdown is devoted to social unrest. Of course, the press serves only to exaggerate feelings and does precious little to inform. Many lost their savings overnight; one has to ask how and why this happened. It is clear that banking was guilty of bad thinking and it is awful that the same bankers have walked away rich while those they were supposed to be working for carry the cost. For example, the average loss to each Icelander was $350,000, The government failed (because the banking had been more extreme). Consequential job losses are counted in millions, perhaps several percent per country. These are matters that cause people to want to change countries — which goes quite some way to explaining the demand for immigration into Britain.

Foreclosures in the US were 2.25 times higher in 2008 what they were in 2006, some 860,000 (source, RealtyTrac). Of course, such figures are not evenly distributed; 4.5% of homes in Florida and in Arizona filed (or were filed) for foreclosure. There were 3.1 million US foreclosures, almost 2% of households receiving a notice. Given that when Fanny and Freddie’s collapses occurred there was a moratorium on further foreclosure, it is surprising that these numbers are so high and that the number falling homeless so proportionally high. That points very well to the original criticism of the whole affair, that credit was being given to those people who could least afford it. Which points very well to the rise of populism in the US and directly to the election of Donald Trump.

And what do we learn?

The financial centres of the world remain in competition with each other to be the biggest. Biggest what, quite, is not too clear, but the driver is still greed. That greed rubs off on the host nations; it remains true for Britain that its biggest earnings source is financial services, by which we mean the stock market, banking insurance and all that goes with them. Essay 259 discusses whether this might not be a good thing.

We might learn that borrowing is a bad thing to do and, at an individual level, we might even take action to defend against the next time this happens. However, at a national level, the only way to climb out of a collapse of this sort is to spend public money, which is always money that has to be borrowed from somewhere (why, I wonder, does what is sensible for an individual not transfer with scale? The answer comes back to the race to the front, because growth is the target.) Spending money to make money is more of the game the banks were playing: when we win it’s our money, when we lose, you bail us out 'cos it was your money. There is a fundamental dishonesty at work here.

We have a clear need for some different measures of success. The ways in which we measure our economies must move to include: reflections of reduction of carbon (etc); time not spent at work (we have called this productivity, where France is good at it and Britain is bad); reflections of our reduction of debt; reflections of moves towards sustainability; perhaps even to include some evidence of integrity (honesty, fulfilment of promises, abiding by the rule of law). Largely false hopes.

What is utterly wrong is this stupidity of racing to disaster. This is, to me, the same idiocy of having too many people. It is the same as the issue of not having enough resources such as water, oil and food. It is the same issue that is driving us to chase money as the measure of success. We need to recognise that success is more than mere survival, it is the quality of the lives we have that measures success. But all of that fails when one person’s comfort is built at the cost of the discomfort of others.

There will be another such crash. I have been pointing to the state of the housing market in China since about 2010; far too much property lies empty and that problem will eventually have its due effect. We will continue to trust, in general, that our property does not go down in value, but we ought to think hard about the assumptions we make in valuing a property. Other assets are held in, for the most part, financial institutions of the very sort that the 2008 crash was caused by. My own pension was worth, on retirement, about 65% of what I expected ten years earlier. I do not see what I can do to defend against another such occasion, which is likely to cause my assets financial to reduce dramatically in value.

Not true; I do see what to do. I need to own property that runs for as little cost as possible, because the running costs are the things that will change. If the future means that it is not the value of a property but the existence and ownership of one and if the future problem might well be access to food and similar fundamental resources, one can see a route towards decisions. On the way, though, one is in danger of dismissing fundamental assumptions such as continued good health and a stable nation.

DJS 20161122

It has occurred to me subsequently that all the subsequent policies in US government, irrespective of party source, serve to benefit the financial sector. Not to improve it, to assist it do more of the same. Look at the response to the 1907 crisis and how that is different to what happened after 1933-6. We have allowed banking to rule. Essays 258 and 259 follow up on this thought.

I discovered, in my own accounts, that one of my own pension funds lost some 30% of value between September and December of 2009. That would explain quite a lot in terms of overall pension performance (I have been unimpressed). If applied to all my pension provision (the fund values are so often simply not available, more so when you live outside the country) represents at least £50k vanished —just of my own assets. Apparently they weren't mine after all. The banks expect us to trust them? Why, pray?

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/FINANCIALSECTOR/Resources/J2-BearStearnsCaseStudy.pdf

https://fi.ge.pgstatic.net/attachments/687bce51ac68418d88aa49d042cbb1e2.pdf

http://joeg.oxfordjournals.org/content/11/4/587.short

Abstract: The recent financial crisis, with its origins in the collapse of the sub-prime mortgage boom and house price bubble in the USA, is a shown to have been a striking example of ‘glocalisation’, with distinctly locally varying origins and global consequences and feedbacks. The shift from a ‘locally originate and locally-held’ model of mortgage provision to a securitised ‘locally originate and globally distribute’ model meant that when local subprime mortgage markets collapsed in the USA, the repercussions were felt globally. At the same time, the global credit crunch and the deep recession the global financial crisis precipitated have had locally varying impacts and consequences. Not only does a geographical perspective throw important light on the nature and dynamics of the recent financial meltdown, the latter in turn should give impetus for a more general research effort into the economic geography of bubbles and crashes.

https://scholar.google.co.uk/scholar?q=2008+financial+crisis+US+foreclosure+numbers&hl=en&as_sdt=0&as_vis=1&oi=scholart&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjZiLyVrrzQAhULC8AKHQoJCysQgQMIGDAA

https://fi.ge.pgstatic.net/attachments/687bce51ac68418d88aa49d042cbb1e2.pdf

http://ceics.org.ar/english/mosley20081.pdf

http://econ.tu.ac.th/class/archan/RANGSUN/EC%20460/EC%20460%20Readings/Global%20Issues/Global%20Financial%20Crisis%202007-2009/Global%20Financial%20Crisis-%20Topics/Effects/Credit%20Crunch/Deciphering%20Liquidity%20and%20Credit%20Crunch%202007-2008.pdf

http://econ.tu.ac.th/class/archan/RANGSUN/EC%20460/EC%20460%20Readings/Global%20Issues/Global%20Financial%20Crisis%202007-2009/Global%20Financial%20Crisis-%20Topics/Effects/Credit%20Crunch/Deciphering%20Liquidity%20and%20Credit%20Crunch%202007-2008.pdf

http://www.stockpickssystem.com/housing-market-crash-2007/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subprime_crisis_impact_timeline

http://www.investopedia.com/articles/07/subprime-blame.asp

http://www.investopedia.com/articles/pf/07/subprime.asp

Films on this topic include:

Inside Job, an Oscar-winning documentary about the banking crisis

Meltdown, complete on YouTube [2:49] a documentary The Big Short, though you really should read the book by Michael Lewis. Chapter One alone tells you enough to have been able to see this coming if you had been awake and in the business. I downloaded the book for free in pdf form. I feel that is not right; there should be something from me to the author. Try here. Long for short: the argument is that it was greed but that underneath that greed was a layer of unbelievable stupidity, not actually understanding their own businesses. It does nothing for one's trust in the financial markets.

Notes from the video, “Meltdown”: US housing market very cheap loansSub-prime marketsVast scale of bank fraud, lending money that could not be collected, The loans were sold back to Wall Street, largely unregulated. The band-wagon was living off the streams, not the money, “toxic assets”Mozilla ? Mozillo Rezillo?Phil Angiledes points that no-one was taking responsibility for the failed, toxic. sales. First started going wrong in London, “easing financial regulation”, a competition between Wall Street and the City in being No1 financial centre. Lots of false assumptions, such as ‘the market always goes up’. Analysts not analysing but lying. ‘The age of irresponsibility’ caused by the bonus system and failure to regulate. Easy credit makes a housing boom. Those left holding the loan are at risk.

Then GW Bush appoints 2006 Hank [henry] Paulson to US Treas Sec. Aggressive, combative style. Calif housing market slide, so credit excess recognised, then see the sub-prime problem. Disaster waiting to happen.

20070809 Paris, BNP Paribas stopped withdrawals (froze) from 3 funds exposed to sub-prime mortgages. Inability to “value their securities” Guardian report see security explanation

London 13 Sep 2007. Adam Applegarth NRock applies for ‘emergency financial support’ (imminent bankruptcy?) immediate run on the bank (taking money out of accounts). UK response slow, over two days. Wall Street did NOT react; interconnectedness not recognised.

20080124 the US reports a big drop in US home sales - did anyone notice?

When US caught the same cold, they noticed but not until March 2008 . Jimmy Cayne , Bear Stearns, the US’s 5th largest bank fell over. The question on early Friday 14th, was whether to allow Bear Stearns to fail, Money was lent to Bear over the weekend and by the Sunday night the Fed reserve gave 30 $ Billion to JP Morgan to buy the assets of Bear. see the WSJ article here. Note that Bear Sterns shares went from $170 in 2007 to $2 at the point where JPM take over. This is the point at which the idea that some banks are “too big to fail” takes hold.

Financial exposure is the amount that can be lost in an investment. For example, the financial exposure of purchasing a car would be the initial investment amount, minus the insured portion. Knowing and understanding financial exposure, which is just another name for risk, is a crucial part of the investment process.

20080907 UG govt bails out Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (firms who guaranteed many sub-prime mortgages) 20080915 Lehman Bros (4th biggest US investment bank, CEO Dick F[??]uld) files for bankruptcy, being ‘exposed’ to the sub-prime market. Not rescued. This is a key moment, for which Hank Paulson is blamed. Though blame is a wrong choice; understanding is required. essay topic for historians and economists. question: is there a point at which the government rescues anyone, including a bank, from making stupid decisions? Paulson might yes but that was not such a moment. Let ‘em burn. Perhaps it is a matter of fiscal responsibility - can I use public money for this?The message sent was that ANYONE could fail, that no-one was to big to fail. This is perhaps the big issue.Suddenly there is no trade credit to be had, so equally suddenly assets have to be sold (at what would feel like stupidly low prices) to realise (literally, make real) some value.20080917 HBOS ( ) is rescued by Lloyds after a drop in share price.

Something in Meltdown not covered by the Guardian takes us to AIG, American International Group, the world’s largest insurer. Enter Joseph Casino in London. He insured companies against failure of their business partners. Which is great until there’s a big event. Result: AIG was saved by 85 $ billion. So some people are not allowed to fail. Issue here is what was the next domino? GE for example?

20080921 Both Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan Chase change from investment banks to bank holdings companies.20080925-29 Washington Mutual and Wachovia collapse. 20080930 this hits Ireland, the big commercial banks Glitnir, Kaupthing, and Landsbanki collapse. 200810 TARP, troubled asset relief program, came from Hank Paulson. Congress said no, they would NOT bail out the financial incompetence. He actually made it work eventually. 700 $billion !! Signs of depression came anyway.

8 October 2008 Amid the worst ever week for the Dow Jones, eight central banks including the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, and the Federal Reserve cut their interest rates by 0.5% in a coordinated attempt to ease the pressure on borrowers.

13 October 2008 To avert the collapse of the UK banking sector, the British government bails out several banks, including the Royal Bank of Scotland, Lloyds TSB, and HBOS [the holding company for the Bank of Scotland, often thought to be the Halifax Bank of Scotland and including what was the Halifax]. The deal is thrashed out over the weekend, and well into the small hours of Monday morning.

It is worth reading this, at Wikipedia, particularly section 1.2.

Paul Myners, City minister 2008-10

"RBS, HBOS and Lloyds were experiencing a professional bank run, where the markets were no longer willing to fund the UK banks. That's why we stepped in. We will never appreciate how close we came to a collapse of the banking system"

7 November 2008 Figures show that 240,000 Americans lost their jobs in the last month

12 November 2008 After criticism from high-profile economists, Hank Paulson announces drastic changes to TARP. He cancels the acquisition of toxic assets, and decides instead to give banks cash injections

20081113 At some point here Paulson calls in the four largest banks in order to give them public money – indirectly this will stop further foreclosures on housing."It was totally clear nobody knew what they were doing. Hank Paulson would change his plans and his public statements on approximately a daily basis. It also became clear that they were not going to punish people or change the nature of the system.” Large amounts of money paid to Wall Street, 9 banks, 00 $millions [what did the taxpayer get out of this?] Protests all over Europe at the sudden shrinking of economies. Merkel tells other countries to deal with their own problems. This emphasises the failure of Europe (it may predict it) and PIGS stand out here. Regional banks in Germany failed. Leverage at 30:1 and worse !! [……]

14 November 2008 The G20 meets for the first time since Lehman's went under, in a meeting that was compared in significance to the Bretton Woods summit in 1944

10 December 2008 "We not only saved the world …" In a slip of the tongue at PMQs, Gordon Brown reveals how highly he rates his role during the financial crisis

2 April 2009 The G20 agrees on a global stimulus package worth $5tn

27 August 2009 Adair Turner, the chairman of the Financial Services Authority, calls some banking activity "socially useless”

10 October 2009 George Papandreou's socialist government is elected in Greece. Just over a week later, he reveals that the hole in Greece's finances are double what was previously feared

27 April 2010 Greek debt is downgraded to junk

2 May 2010 In a move that signals the start of the Eurozone crisis, Greece is bailed out for the first time, after Eurozone finance ministers agree loans worth €110bn. This intensifies the austerity programme in the country, and sends hundreds of thousands of protesters to the streets

28 November 2010 European ministers agree a bailout for Ireland worth €85bn

5 May 2011 The ECB bails out Portugal

21 July 2011 Having failed to get its house in order, Greece is bailed out for a second time

5 August 2011 S&P downgrades US sovereign debt

12 February 2012 Greece passes its most severe austerity package yet

12 March 2012 The number of unemployed Europeans reaches its highest ever level

12 June 2012 The level of Spanish borrowing reaches a record high

26 July 2012 Unexpectedly, ECB president Mario Draghi, above, gives his strongest defence yet of the Euro, prompting markets to rally