I’m going to assume you have a habit that you wish to change. No monkeying around ¹.

Establish clearly what this habit does for you; what you get out of it. On the way you’ll see a route to something to displace the bad habit with. You may well be usefully sidetracked into recognition of a different problem – that this bad habit is a symptom of an entirely different issue that is what should really be attending to.

What is it that triggers this bad habit? When you identify these, do something to remove them. The trigger might be a person, or an event, or a site, or an action.

So, having identified what makes you do this and what you might displace it with, next you need to visualise that change — see yourself with the ability to make that change happen. Source [1] refers to the meme “nerves that fire together wire together”, entirely new to me. The theory is that the more you push the idea, so the path in your head that turns a thought into a habit is grown. Think of it as making a new pathway; the more you traffic it, the more definite the path becomes.

There are three slightly negative ideas that go with these positive actions. You may need to start small, you may backslide and you know that progress won’t be immediate. My wider reading says it takes six weeks to generate a new habit from first action to not thinking about it. ² If the new habit is somehow blocked from occurring, don’t let it be entirely lost, do some rather than none. The backsliding, falling back into the old habit, is to be allowed for—not expected but tolerated; you may need to rethink some of the earlier reasons for the habit you’re trying to remove. You may need to write it down.

James Clear [2] takes a different approach. He says there are four stages: Cue, Craving, Response and Reward. He say these are the fundaments of every habit. In this analysis the cue is the trigger. The craving is the promise of whatever the reward is (perceived to be). The response is the thing that is subsequently designated as the habit, that bit of behaviour that you might be wishing to change. The completion of the cycle is when the reward connects to the cue. So the problem part is, obviously, the cue/craving and the solution part is the response/reward.

Now, while I started with the objective of removing a bad habit, not all habits are bad and we might persuade ourselves to develop good habits. Displacing bad habits with good ones is, once identified, a no-brainer. Recognising that an awful lot of what call normal behaviour is actually a serial expression of habits is a little uncomfortable, but quite accurate. I think the hard part is identifying (in the latter terminology) the cue and craving so as to replace the response and reward. So in this case a Good Habit has an obvious cue, an attractive recognition of craving, an easy response and a satisfying reward—perhaps just that, satisfaction at doing something ‘right’. Conversely, to remove a Bad Habit, the cue needs to be made invisible (not seen, ignorable), the craving has to be perceived as no longer attractive, the response has to be seen as being difficult and the reward somehow unsatisfying. All of which sounds much too simple to be hard, doesn't it?

An example, from recent conversation with the darling daughter: habit appears to leave the iron on or, more exactly, to leave the iron so that you cannot remember if you left it on. The solution is to unplug the iron and leave the plug beside the iron. The new action is the plug placement. Actually, any distinct action that moves the unplugged but hot iron to a safe place will suffice. A very similar set of actions might apply to electric kettles of the sort with a powered base plate; the identified issue is that you might turn on the kettle without thinking to fill it, then when it is filled you put it back on the plate, when it is empty it is not on the plate. When you come to the kettle wanting a hot drink, the kettle position tells you whether you need to fill it.

The real problem is that what you think is a habit may well be a displacement activity. In this case your issue is to do with self-honesty, with facing up to issues that you have been avoiding. For these you may need help. I wonder immediately if the displacement activity might be swapped to something that brings ancillary rewards (swap biscuit for fruit, swap a video for exercise, swap spending for creating). That doesn’t fix whatever you’re trying to avoid, but it might make circumstances change so that the other problem simply disappears.

I have seen, far too often, people end up doing nothing because they can’t see their way to a total solution. The pragmatic and practical person says that you fix what you can, you don’t fix what ain’t broke, and what you can’t fix might be avoidable.

Source [6] indicates that much of our habit-based activity is cued by environment. So a change of environment makes it easier to change a habit—because the new situation encourages us, at the least, to modify behaviour, so this is also our best opportunity to change behaviour that significant bit more. I found this [6] saying things I recognise as successful strategies; among these I include using different screen tech for particular purposes: I don’t browse on my phone, I do puzzles and read only on a tablet, and so on. Good habits are ones you have made easy and if you want to improve a habit, make it easier. Similarly, make bad habits harder. If you want lots of examples, use the source list.

Source [8] adds some good background, and I summarise—you want more, go read it yourself. We behave as if we have a daily limit on ability to make decisions, which we tend to call mental energy. Irrespective of the size of the tank, we improve behaviour if we reduce the number of decisions required. Therefore, we can deliberately create habits that reduce the need for decisions, such as reducing clothes choices (preparing that the previous night works, too). Boring but productive; Instead of wasting your mental energy on things that you consider unimportant, save it for those decisions, activities, and people that matter most to you.

If you work in a world that loves having targets, then one suggestion from [9] is to enlarge your vocabulary, using goal for the big, macro stuff and quota for the small stuff. I was struck by two examples given:

(i) having identified a problem with meeting the dentist’s demand on flossing, BJ Fogg promised himself (made a commitment) to floss one tooth every time he brushed his teeth. More were allowed, but one was mandatory. Result: about once a week it was just one tooth, most days the job was done properly. See Fogg’s, Tiny Habits, also found through [9].

(ii) Smokers attempting to quit were asked to try to smoke the same number of cigarettes every day [were found to] gradually decrease their overall smoking— even when they are explicitly told not to try to smoke less. See.

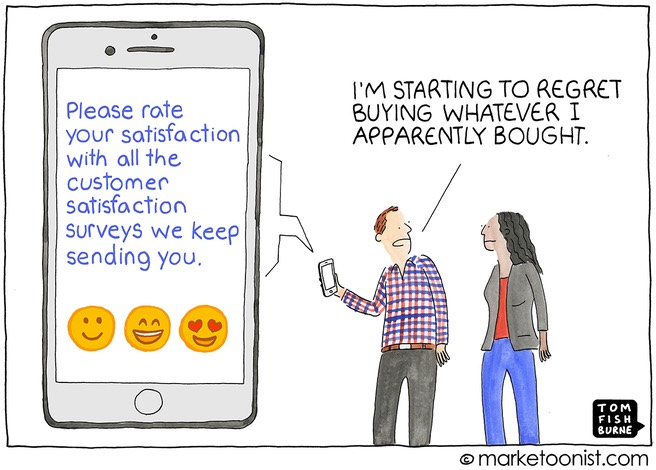

We have a modern meme that choice is good and more choice is better. See [10], ³ which casts this into question and has resulted in some acceptance that choice is seen as a demotivating influence, which makes it bad for us in attempting to cope with life. I’m not sure what I find more interesting here, the ready acceptance of the conclusion or the conclusion itself. Coupled with the ideas in Happiness, 246, I’m willing to agree that ‘Choice is demotivating’ is correct. Hence the term choice overload, from which Herself suffers whenever we go to the supermarket. This wonderful illustration⁴ is from [12]. I looked for further research following the Jam Experiment, ³ finding a lot of agreement, summarised perhaps by the meta-analysis of [11]. This identifies four key factors—choice set complexity, decision task difficulty, preference uncertainty, and decision goal—that moderate the impact of assortment size on choice overload. Cutting out the generally dense stuff ⁵, this confirms that far too much choice is indeed a Bad Thing. I think I showed in an earlier essay that what happens with too much choice is that we are diverted from our objective. Mansplaining versions: (i) just pick one, dammit (ii) don’t let yourself be diverted off-task. Oh, did I just do that myself?

DJS 20181116

Father’s birthday, if he was still with us.

Top pic from Charles Duhigg

My examples from personal discovery:

I reverse into a parking space or use a 'through and through’ so that departure is easy. The identified problem that beginning a drive with reversing leads to many more difficulties, including accidents. This extended recently to finding spaces in car parks nearer the exit route. The perception is that I drive far better when in some sense warmed up.

I try to put things down in particular places (don’t put it down, put it away) so that they are where I expect them to be. That is not an age thing, since I’ve done it for decades. The reward is that things are where I expect them to be. The trick is to make those things I want often be near at hand.

We no longer have biscuits in the house, but we have fruit as replacement when craving a sugar hit.

When annoyed at having to wait for Herself, because we have dramatically different ideas about timeliness, I have replaced ranting with stretching exercises. Fortunately these are not recognised as displacement for ire and they do reduce such tendencies. A good solution, then.

Missing running because the weather is inclement (any excuse to miss) is cured by joining the gym, by keeping a set of kit ready — and promising oneself to have variety. That last has yet to happen. One good solution is to change the run route so that the clock-chasing—which often causes damage—is avoided.

I was having a problem doing enough stretching; a partial solution was to use the stairs as a cue to stretch; use the stairs, must stretch on the bottom four steps when going up. It adds up quickly. Beware allowing exceptions, though; the habit has to be EASY. A related set of stretches has modified—chaining habits together—so that it is part of the ‘going to bed’ routine (on a ‘normal night’).

DJS 20181116

Father’s birthday, if he was still with us.

Top pic from Charles Duhigg

I don’t have the habit of looking at my phone in the morning to check for messages.

I don’t look at email until after the brain training puzzles.

I fail to grow fingernails, but also vegetables. I fail to do gardening.

1 If you’re a monk or a nun, changing a habit is easy; find your change of clothes and get on with it. EAL readers: a habit is a long loose gown worn by several religious orders. Some definitions confuse the gown with the headgear. It may be that ‘habit’ has become the umbrella term for the complete uniform.

2 Serious dispute about this. Many think three weeks, some say three months. It would be nearer the truth to say ‘it depends’. [9] has a bit of a rant about this, which I quote: One of the big habit myths is the belief that it only takes 21 days for a habit to form. Through the use of weasel words and un-cited “research,” personal development dweebs try to sell programs on this magic 3-week span. Actual research on the subject shows this popular belief just isn’t true: how “long” it takes to form a habit depends on the individual, the habit being formed, environmental factors, etc. Like most research, it’s far more messy, and doesn’t make for great book titles like 21 Days to Blah Blah Blah… Furthermore, this outlook on habits (“I just have to get to X days…”) diminishes the real benefit of forming a habit in the first place: to change your lifestyle, which ultimately leads to a more rewarding day-to-day. Reaching an imaginary number of days is not how you get results.

3 Abstract of [10], The Jam Experiment. Current psychological theory and research affirm the positive affective and motivational consequences of having personal choice. These findings have led to the popular notion that the more choice, the better—that the human ability to manage, and the human desire for, choice is unlimited. Findings from 3 experimental studies starkly challenge this implicit assumption that having more choices is necessarily more intrinsically motivating than having fewer. These experiments, which were conducted in both field and laboratory settings, show that people are more likely to purchase gourmet jams or chocolates or to undertake optional class essay assignments when offered a limited array of 6 choices rather than a more extensive array of 24 or 30 choices. Moreover, participants actually reported greater subsequent satisfaction with their selections and wrote better essays when their original set of options had been limited.

4 https://marketoonist.com/cartoons for more Tom Fishburne content, with one that hits the spot for me this week. Looking at these rapidly put me into a state of complete indecision; it’s called browsing, I think.

5 outline of [11] Despite the voluminous evidence in support of the paradoxical finding that providing individuals with more options can be detrimental to choice, the question of whether and when large assortments impede choice remains open. Even though extant research has identified a variety of antecedents and consequences of choice overload, the findings of the individual studies fail to come together into a cohesive understanding of when large assortments can benefit choice and when they can be detrimental to choice. In a meta-analysis of 99 observations (N = 7202) reported by prior research, we identify four key factors—choice set complexity, decision task difficulty, preference uncertainty, and decision goal—that moderate the impact of assortment size on choice overload. We further show that each of these four factors has a reliable and significant impact on choice overload, whereby higher levels of decision task difficulty, greater choice set complexity, higher preference uncertainty, and a more prominent, effort-minimizing goal facilitate choice overload. We also find that four of the measures of choice overload used in prior research—satisfaction/confidence, regret, choice deferral, and switching likelihood—are equally powerful measures of choice overload and can be used interchangeably. Finally, we document that when moderating variables are taken into account the overall effect of assortment size on choice overload is significant—a finding counter to the data reported by prior meta-analytic research.

[1] https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/renaissance-woman/201607/how-change-unhealthy-habits

[2] https://jamesclear.com/three-steps-habit-change and

[3] https://jamesclear.com/how-to-break-a-bad-habit

[4] https://psychcentral.com/lib/7-steps-to-changing-a-bad-habit/ says 28 to 90 days to change a habit

[5] https://www.inc.com/melody-wilding/psychology-says-this-is-how-you-change-a-bad-habit-for-good.html

[6] https://www.sparringmind.com/changing-habits/

[7] 2nd How to change a Habit diagram. from https://www.inquasar.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/how-to-change-a-habit-flowchart-.jpeg

[8] https://hbr.org/2012/09/boring-is-productive.html

[9] https://www.sparringmind.com/good-habits/

[10] https://faculty.washington.edu/jdb/345/345%20Articles/Iyengar%20%26%20Lepper%20(2000).pdf The Jam Experiment ³.

[11] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1057740814000916

[12] https://medium.com/crobox/choice-overload-help-were-drowning-in-choices-e2b2deae6c94